From Illinois to Playboy: Remembering Hugh Hefner

The life of a rebellious, controversial visionary

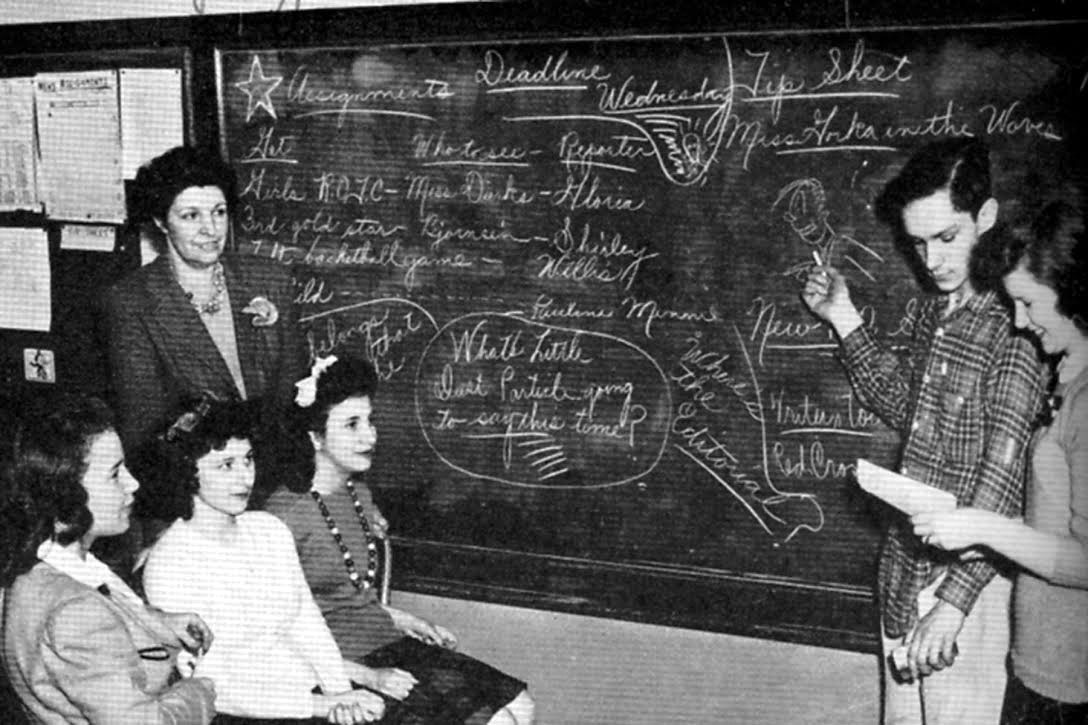

Hugh Hefner draws a cartoon on the blackboard during his time as a student. Hefner graduated in 1949.

Oct 2, 2017

Last updated on Oct. 4, 2017 at 02:48 p.m.

For four months in the spring semester of 2000, Josh Schollmeyer devoted his life to understanding Hugh Hefner. He wasn’t interested in the then 74-year-old’s lifestyle of exuberance. Rather, he wanted to know how Hefner, an army veteran who lost his virginity at 22 in a Danville hotel, went from University of Illinois undergrad to America’s playboy.

Schollmeyer, a University alumnus, came up with the idea in February and spent the next several months researching Hefner’s time on campus for buzz Magazine’s end-of-the-year issue. At the University Archives, he pulled up the “Hef File.” For every photo Hefner was documented in, Schollmeyer wrote down all accompanying names. The list totaled roughly 200 people. Every night, he cold-called four or five names.

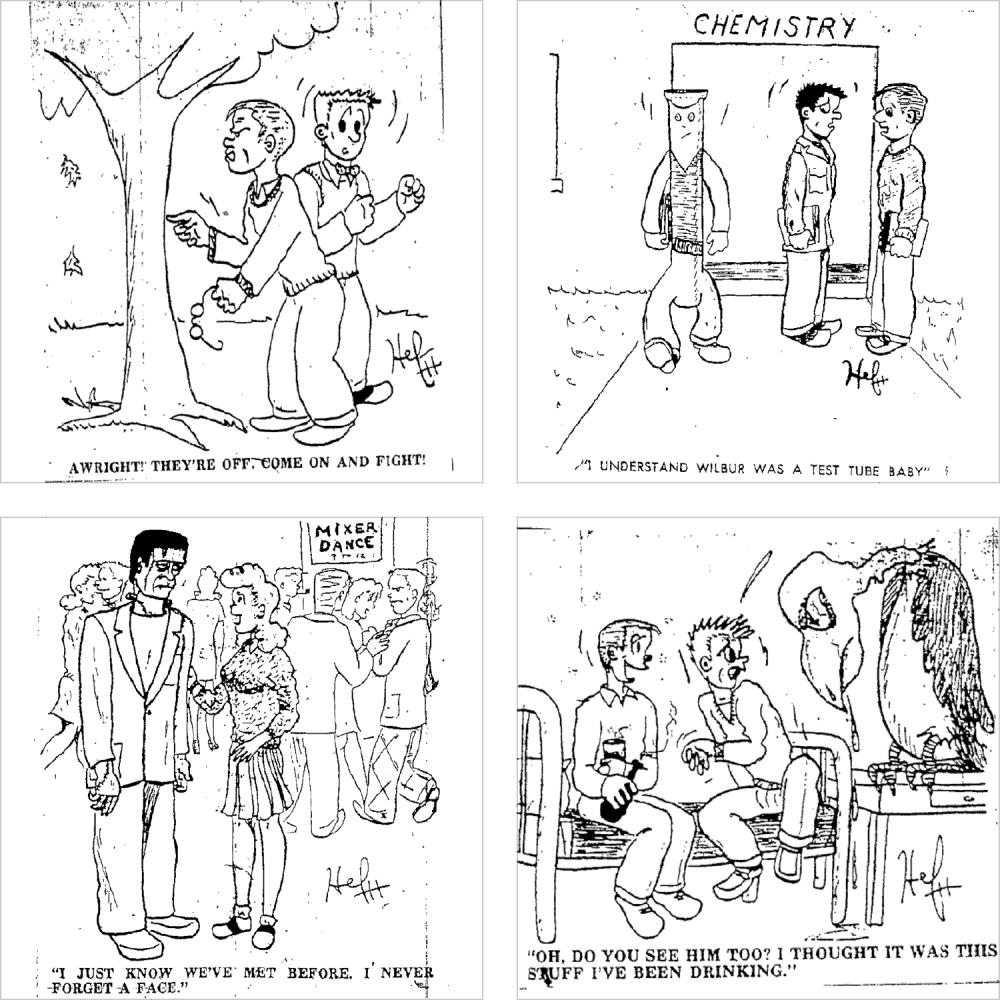

Schollmeyer started to reconnect Hefner’s campus years and his inner circle of friends. Hefner wrote a comic strip called “School Daze” throughout high school and college. (He renamed it “G.I. Daze” during his two years in the Army.) Hefner’s friends relayed these stories to Schollmeyer. At the time of Hefner’s death, Schollmeyer estimated 6,000 or 8,000 volumes of his cartoons are housed in the Playboy archive.

By that point, he managed to piece together Hefner’s college years but was missing an essential piece: Hefner himself.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Schollmeyer contacted the Playboy Mansion. He quickly heard back and was invited to spend a week at the mansion for the Playmate of the Year party. He recalls being the youngest male in attendance by at least two decades. During the party, he remained silent, in awe and in over his head of the celebrities, the Mansion and Hefner.

“I don’t think in my wildest imaginations I thought I would be getting invited to the Playmate of the Year party,” Schollmeyer said.

The day after the party, Schollmeyer was crouched over his computer at the Days Inn in Inglewood, California, about 11 miles away from the mansion. He had five days to turn a semester’s worth of research into a single profile of a dynamic, polarizing man.

The article ran, received positive reviews from Playboy, and Schollmeyer was offered a job to assist famed writer Bill Zehme for Hefner’s autobiography, “Hef’s Little Black Book.”

Within 18 months, Schollmeyer went from an eager postgrad in Champaign to a writer living in the Playmate House, just down the street from the mansion.

“That time with Hef changed my whole life,” he said.

Schollmeyer moved up the Playboy ladder, initially hired as a senior editor in 2009 before ultimately becoming a vice president. He left the company in 2014 to start his own men’s lifestyle publication, MEL Magazine — a self-described 21st-century response to publications like Playboy.

“I live not too far from the Days Inn that I held up in to write that article,” Schollmeyer said.

Schollmeyer had a “front-row seat” to the legacy that Hefner created. He credits Hefner with changing the narrative of what it meant to be a single man.

“You were the odd uncle if you didn’t get married right out of college,” Schollmeyer recalled Hef telling him during the 2000 trip.

While at the University, Hefner completed his degree — a major in Psychology and a double minor in creative writing and art — in two-and-a-half years. He wanted to catch up to Millie Williams, his then-girlfriend and first wife.

Hefner worked as a cartoonist for The Daily Illini and briefly managed Shaft magazine, a precursor to Playboy. It was during this time that he first broke cultural norms — taking nude photos of Williams despite criticism from his friends.

Hefner graduated from the University in 1949, accepting a job at Esquire magazine a few months later. By December 1953, Marilyn Monroe was gracing the cover of the first issue of Playboy, and the controversial magazine was flourishing.

“He became this icon, but he was just a really nice guy with a dream and had a great personality with a fantastic sense of humor,” said Karen Shivley, a former Playboy employee.

Shivley, a former University student, worked as a switchboard operator during Playboy’s first year in Chicago. After her summer with the company, she went back to Champaign for the fall semester. A year later, Hefner moved the company to its Ohio Street location, and she once again applied for a job. Shivley was hired as the assistant to Hefner’s private secretary, Pat Pappas.

Hefner and Shivley began dating during her time at Playboy. She even posed once as a Playmate during their six-month relationship. However, Hefner was concerned about her father’s reaction, and it was never published.

“‘Your father will be so upset when he walks in one day and the people that work for him, the guys that work for him have you up on their wall, naked,’” Shivley said Hefner told her.

Hefner’s image of a “sex-crazed maniac” was one he decided upon himself, Shivley said. When they dated, he was a one-woman man focused on art and authenticity.

“His dream was to make (Playboy) something that people picked up — aside from the beautiful women — that they actually picked up and read,” Shivley said.

She credited Hefner with speeding past his initial goal. But by the time he did so, Hefner was portrayed in the media as a different man, with a polarizing image as an abuser or a liberator. It wasn’t how she knew or remembered him, she said.

“Who he was just disappeared,” she said.

It’s this image of Hefner that Schollmeyer wrestled with in recent years, noting that he modeled MEL after Playboy in the ’50s through ’70s, not its current state.

“Anybody who’s ever worked there, you’re going to be naturally defensive,” Schollmeyer said of his time at Playboy. “We were complicit in something.”

Schollmeyer said Hefner stood as a leader in civil rights and sexual liberation since Playboy’s birth. He bought back Playboy clubs in the South after segregation policies were implemented. He donated money to the Kinsey Institute for the study of sex and supported LGBT rights as early as the 1950s.

But in recent years, his image has rested more on his relationship with women than activism.

“What disappoints me about him and the legacy is I think he stopped standing for those things in the 1970s and 1980s,” Schollmeyer said.

Samantha Jones-Toal contributed to this report.

Correction: In an earlier version of this article, Karen Shivley’s last name was misspelled. The Daily Illini regrets the error.