School-based plain water intervention could reduce risks of obesity

Source: Center for Disease Control

Nov 28, 2017

A new study says making plain water more accessible during school lunches could prevent around 57 million children in the U.S. from becoming overweight or obese and decrease medical and indirect societal costs associated with these problems by more than $13 billion.

The study, conducted by kinesiology and community health professor Rupeng An, analyzed the costs and benefits from public and private schools nationwide encouraging students to drink more plain water by making it more accessible.

An’s findings expanded on a pilot program conducted in 1,200 elementary and middle schools in New York City between 2009 and 2013. In the original study, water dispensers were placed in school lunchrooms and consumption of water at lunch tripled. Researchers associated plain water consumption with small but significant declines in student’s risks of being overweight one year later.

The cost of expanding the program to all schools nationwide would cost a total of $18 for each K-12 student. However, over each person’s life the average net benefit is estimated to be $174, or in total $13 billion, making the program potentially promising if adopted nationwide, An said.

To come to these conclusions the study used a method called cost-benefit analysis, which involves estimating the total expected cost of each option against the total expected benefits to see whether the benefits outweigh the costs, and by how much.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

An’s cost analysis assumed that plain water intervention would lead to permanent reductions in cases of adult obesity, as well as medical and indirect costs such as absenteeism and reduced productivity.

“The plain water intervention has already been adopted in a majority of New York public schools. Given the modest cost, I would say that such intervention has the potential be to adopted nationwide,” he said.

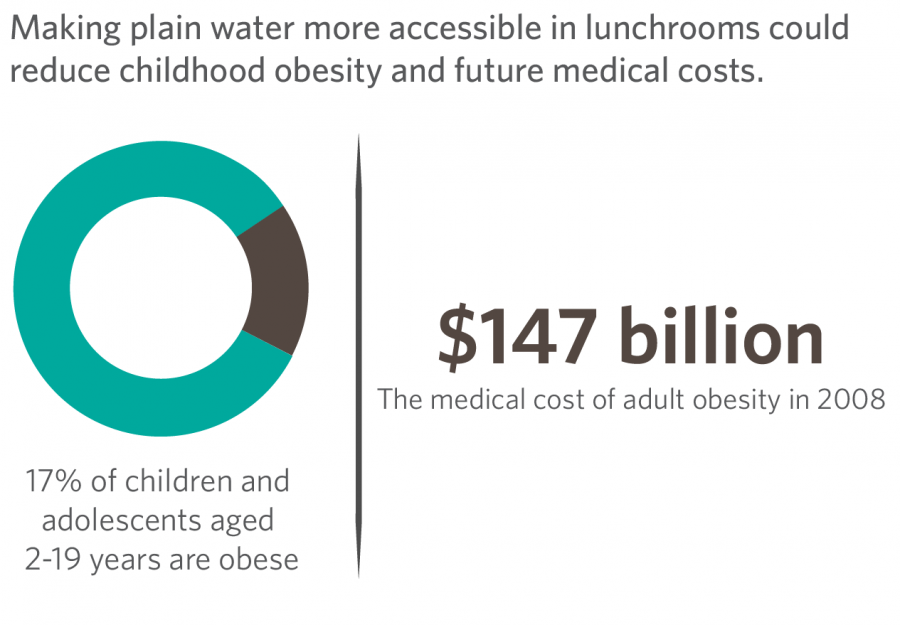

According to the new study, currently approximately 12.5 million or 17 percent of children and adolescents between two and 19 years of age are obese, tripling the childhood obesity prevalence in 1980.

The plain water intervention will help decrease risks of obesity by changing the environment of students to be more healthy, nutrition professor Manabu Nakamura said. By offering water instead of high-calorie drinks, it will will decrease risks, he said.

“Several small-scale interventions to improve plain water access in school settings have documented increased water consumption, reduced discretionary calorie intake, and/or healthier body weight status among students,” An said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, six out of 10 youths were found to drink a sugar-sweetened beverage on a given day between 2011 and 2014. The plain water intervention would hope to decrease these numbers.

However, Nakamura said the intervention will only have as much impact as people choose to follow the policy or drink plain water.

“You cannot just guide someone with policy. The policy can definitely help, but it is not the primary solution,” Nakamura said.

The cost-benefit of a school-based water intervention competes favorably with other mainstream population-level childhood obesity interventions and policies, An said.

Policies such as imposing excise taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages and enforcing nutrition standards for foods and drinks sold in schools outside of meals have all reduced risk of obesity or becoming overweight in some way. The plain water intervention in An’s study compares closest with the sugar-sweetened beverage excise tax, with a cost-benefit of $14.2 billion and reduction of childhood obesity cases by .58 billion.

According to the study, the school-based water intervention was estimated to have more of an economic impact among boys than girls due to boys having higher expected overweight reduction rates than girls. Despite this difference, An and his co-authors have suggested the probabilities of both sexes benefiting from the intervention were high.

The study was co-authored by Hong Xue and Youfa Wang, both of Ball State University, and Liang Wang of East Tennessee State University, and was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health.