Graduate student uses AI to advance epilepsy research

Photo courtesy of Yogatheesan Varatharajah

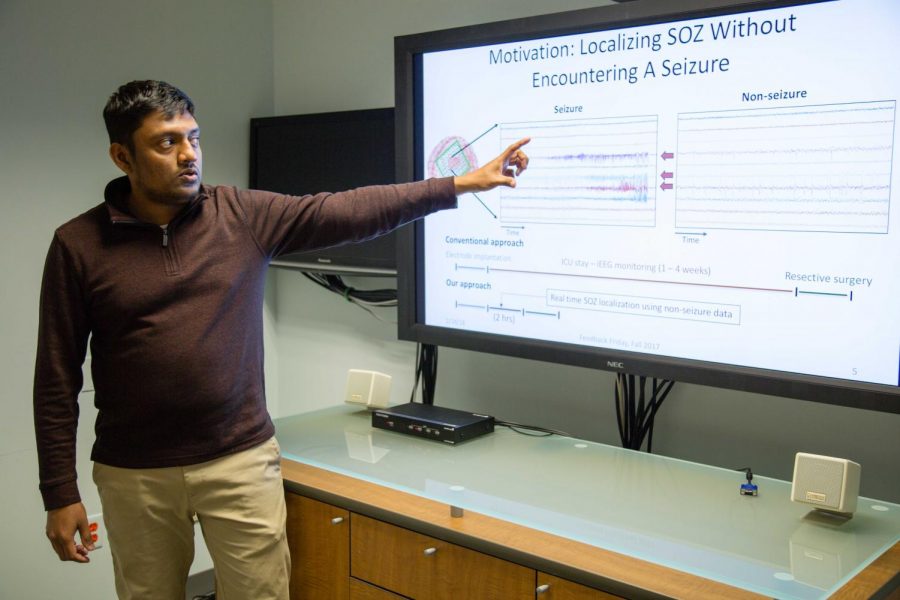

Ph.D. candidate Yogatheesan Varatharajah has developed an artificial intelligence technique that can help identify seizure-causing brain regions for those with epilepsy.

Jan 30, 2018

Last updated on Feb. 1, 2018 at 08:22 a.m.

Artificial intelligence may be the next great medical tool for those with epilepsy, according to a research project done by Ph.D. candidate Yogatheesan Varatharajah.

His research with AI resulted in a technique that can identify the brain regions that generate seizures without requiring the inspection of actual seizures.

“While there is a lot of skepticism about whether artificial intelligence has a negative impact on humanity, we firmly believe that AI can be used to make mankind stronger, and our work is a perfect example of that,” Varatharajah said.

Varatharajah’s technique helps forego the manual way to find these regions, which is done through electroencephalograms (EEG). The EEG test is a way for epileptologists, neurologists specializing in epilepsy, to record information from brain regions by attaching small, flat metal discs (electrodes) to your scalp.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Epileptologists usually wait days or weeks in between patients’ seizures, as the EEG test can best identify regions during those spasms. Automating this process using Varatharajah’s AI software can eliminate the need for multi-day EEG recordings and can save time for doctors .

“Later, we found out that we need not even record seizures, and only non-seizure recordings can be sufficient to achieve accurate identification of seizure-generating regions,” Varatharajah said. “This was even more exciting because it has the potential to transform the way epilepsy surgery is currently performed.”

Usually, in epilepsy research, if a brain region is responsible for seizures, it generates abnormal “sparks” or activity. Varatharajah said past research hasn’t led to any clinically relevant results in identifying seizure-generating regions, and simply finding these “sparks” isn’t enough.

“We identified that in addition to the abnormal activity (sparks), taking their temporal patterns and spatial similarities across different brain regions into consideration can improve the accuracy,” he said.

Varatharajah’s research was done in collaboration with Dr. Gregory Worrell, who is the chair of clinical neurophysiology at the Mayo Clinic. Varatharajah first began his collaboration with the Mayo Clinic one summer, and a University professor, Ravishankar Iyer, encouraged him to look into that program.

“Since then, I have been collaborating with the Mayo Clinic for the past three years, and he is constantly involved in all my projects, providing directions and suggestions to improve my research,” Varatharajah said.

Iyer said the University and the Mayo Clinic have an alliance that connects University faculty and students with Mayo physicians, hoping to bring more engineering and computing technology to medicine. He said it’s been an excellent partnership so far.

“The partnership with Mayo physicians like Dr. Worrell and others in the Center for Individualized Medicine is crucial since they have the domain knowledge and insight that we can learn and leverage,” he said.

Varatharajah said their AI technology is currently in the patenting process and Dr. Worrell is evaluating if they can incorporate it into the usual clinical workflow at the Mayo Clinic.

“The opportunity to develop technology that can augment real human lives is the greatest impact of my research,” Varatharajah said. “We are making every effort to make this possible and soon will be in a position to witness the real impact of our technology in the patients suffering from epilepsy.”

Correction

The article previously stated that Vatharajah’s research eliminates the need for EEGs. This is incorrect. His research actually just reduces the need for multi-day EEG recordings, as he said they still need at least of two hour EEG recordings to do the AI analysis. The Daily Illini regrets this error.