Professor: Social media key to anti-sexual assault movement

Google Trends

Mar 8, 2018

From a camera velcroed to the inside of a toilet, doctors at a major hospital videotape nurses as they change inside the women’s locker room.

In another instance, a factory floorman questions his female employee about her sex life and shows her a picture of his penis. He asks if it’s bigger than her husband’s.

Louise Fitzgerald, a Professor Emerita at the University, is no stranger to cases like these. For the past two decades, she has been hearing and researching stories of sexual harassment in the workplace.

“People would look at me like I was crazy. It was not easy to do research on this topic,” Fitzgerald said. “It wasn’t seen as a serious issue— most people at the time simply thought it was flirting.”

Though the #MeToo movement has left a trail of actors, politicians and executives facing public scrutiny, Fitzgerald speaks about the movement’s potential with measured optimism. She keeps in mind the Clarence Thomas hearings in 1991, a scandal she thought would have been a turning point in the discussion of sexual harassment.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Thomas’ nomination to the Supreme Court was stymied by testimony from Anita Hill, his long-time employee, who alleged Thomas had made inappropriate sexual comments while she worked for him at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Under close scrutiny from the media and the public, Thomas was narrowly confirmed to the Supreme Court.

Unlike the Thomas hearing, which left people in power untouched, the #MeToo movement has managed to topple senators and Hollywood kingmakers.

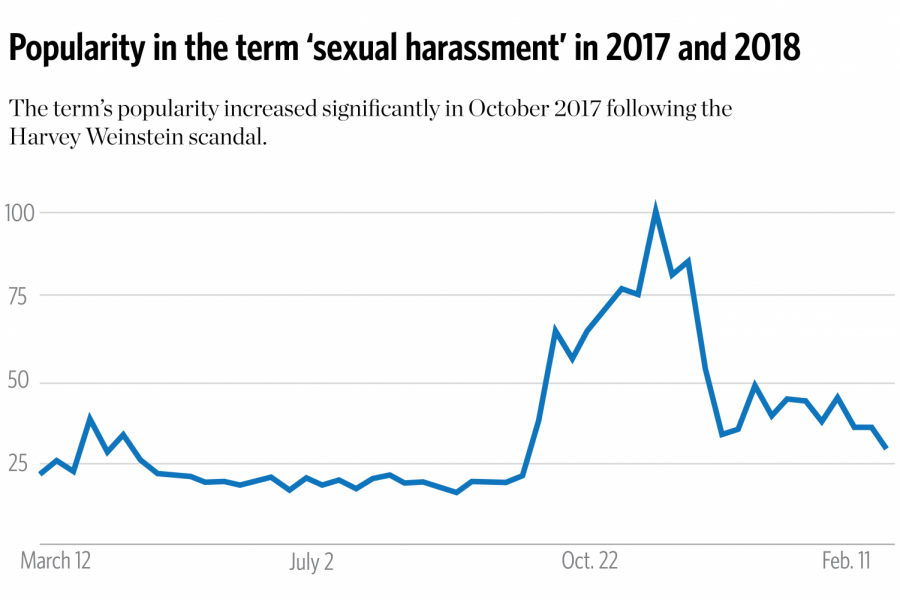

Fitzgerald attributes the bulk of its success to social media, a powerful tool that allowed the Harvey Weinstein scandal to trigger something the Thomas hearings didn’t: A nationwide reckoning of sexual harassment that has leaked below the high profile cases that sparked the movement.

By breaking down barriers of location and industry, Fitzgerald said social media connects women across the country who have shared the experience of sexual harassment.

“Social media taps into what is essentially collective rage at what has been going on ever since women entered the workforce,” Fitzgerald said. “We’re a long ways from solving it (sexual harassment), but I do think it’s on the table now. I think it’s on the agenda and I don’t think it’s going to disappear.”

Fitzgerald predicts social media will give the #MeToo movement the staying power the conversation around the Thomas hearings did not see.

Though Fitzgerald said sexual harassment was widespread among women in the workforce during the hearings, she says few women spoke out about their experiences, and the big push to acknowledge and call out sexual harassment that accompanied the #MeToo movement failed to materialize.

Though the Thomas hearings induced the corporate and legal worlds to view sexual harassment with a new sense of seriousness with the Civil Rights Act of 1991, public conversation surrounding the issue faded away.

Today, Fitzgerald recognizes some of the questions currently being asked about sexual harassment as the same ones she was asked in a 1991 episode of an NPR show.

Fitzgerald recounted being asked, “‘How could this happen? Somebody like that couldn’t do that. Blah blah blah.”

Wendy Heller, head of the University’s psychology department, said social media plays a critical role in sustaining a variety of social movements, from the revolutions of the Arab Spring to the revelations of sexual harassment of the #MeToo movement.

“Overall we’re continuing to make steps in the right direction,” Heller said. “Certainly the #MeToo movement isn’t going to cause everything to go away overnight.”

The EEOC reports that anywhere from 25 to 85 percent of women have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. Fitzgerald said sexual harassment prevention programs need to go beyond instituting policies and instead create workplace cultures unfriendly to sexual harassment.

Fitzgerald likens the process to turning a battleship— a long, slow, continuous effort. She said organizations need to convince their workers that they take the issue seriously, it is safe to report sexual harassment and that the perpetrators will face consequences.

Heller described implicit bias against women as the primary obstacle to putting women in positions of power and reducing sexual harassment.

“When you’re in a hurry and you’re reading 27 applications for a job, you’re going to be taking shortcuts,” Heller said. “If you have stereotypes that women aren’t as good at this as men you’re more likely to activate those stereotypes automatically and not even be aware that you’re doing it.”

Though she said affirmative action policies often encounter resistance, Fitzgerald describes gender parity in the workforce as a powerful tool to reduce sexual harassment.

“When workplaces become gender neutral, or more gender neutral, it will seem more natural, and women will start being seen more as professionals or workers as opposed to that hot chick over there,” Fitzgerald said. “Equalizing the numbers makes it seem more normal and familiar and part of everyday culture.”