University faculty address concerns on U.S. trade deficit

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Apr 2, 2018

President Donald Trump’s decision to add tax on imported goods from China has led to a campus conversation about the potential outcomes of and solutions to the U.S. trade deficit with China.

Candace Martinez, clinical assistant professor in Business, said it is not a good idea to add more import duties.

“If you have two economists in a room, there will be three opinions. But … they agree on one thing — free trade,” Martinez said.

Fabricio d’Almeida, visiting assistant professor in economics, said President Trump is using the threat of a trade war with China to extract a better bargain and to keep his constituents happy.

“Trump’s political base is blue-collar,” d’Almeida said. “He tries to build upon the platform that he can bring back those jobs to them, so that he can keep the political support.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

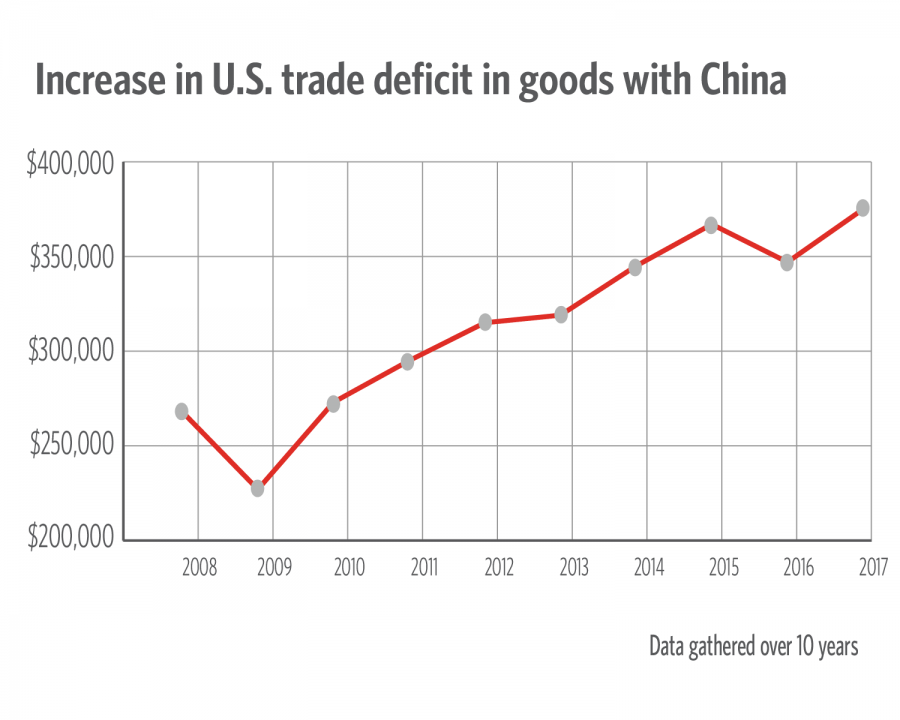

In 2017, the U.S. had a $566 billion trade deficit, according to the U.S. Census Bureau website.

The best solution for the trade deficit would be to increase the savings of American families, d’Almeida said.

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the personal saving rate of the average American last year was less than 5 percent of disposable income.

“Compare that to the saving rate of 17 percent in 1975; we can see the ability for the U.S. to save has been reducing,” d’Almeida said. “While the average Chinese family in the urban areas saved almost 25 percent of income last year.”

Martinez said the problem is that Americans buy too much and save too little.

“You can’t tell people what to buy,” Martinez said. “If you don’t import, eventually it’s called retaliation.”

D’Almeida said if the trade war begins, the price of imported goods will increase, causing American consumers to suffer.

Companies would reduce investments and jobs because of political uncertainty under a trade war, which would negatively impact American corporations, he said.

The flow of U.S. capital to China contributes to the trade deficit, Collin Philipps, a graduate student in economics, said in an email.

“Trade is beneficial to economic systems, but the benefits from trade are not always realized in an equitable fashion,” Philipps said. “Right now, the administration seems to believe that China has reaped huge gains from decades of trade with the U.S., but the U.S. gains have been minimal or negative in some sectors.”

Philipps said many U.S. firms complain they cannot export to China without paying steep tariffs.

“When you consider the loss of low-skill jobs to Chinese firms, you can argue that current trade relations might be worsening U.S. income inequality,” Philipps said.

Philipps said the best solution would be if China relaxed some of its protectionist policies in exchange for the U.S. dropping these tariffs. This would create more trade and economic activity, ultimately benefitting the U.S.

Since Trump announced his decision, the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar to Chinese currency, Renminbi or RMB, has decreased.

“Usually, we see the exporters’ currencies weaken after trade barriers are erected,” Philipps said. “That doesn’t necessarily represent a weakening dollar, at least not immediately.”

Nuo Jin, graduate student in LAS from China, said a trade war would be an economic and political disaster for both countries, but for now he is benefitting from the decreased exchange rates.

“As a foreign student, I believe the decrease of exchange rate is good for me since I can spend less money on tuition fees and other expenses than before. I might be able to take advantage of it for a while,” Jin said.