Research aids process for turning water into fuel

Oct 11, 2018

A world where cars are fueled with water instead of natural gas may become a reality sooner than people imagine, thanks to a team of researchers at the University.

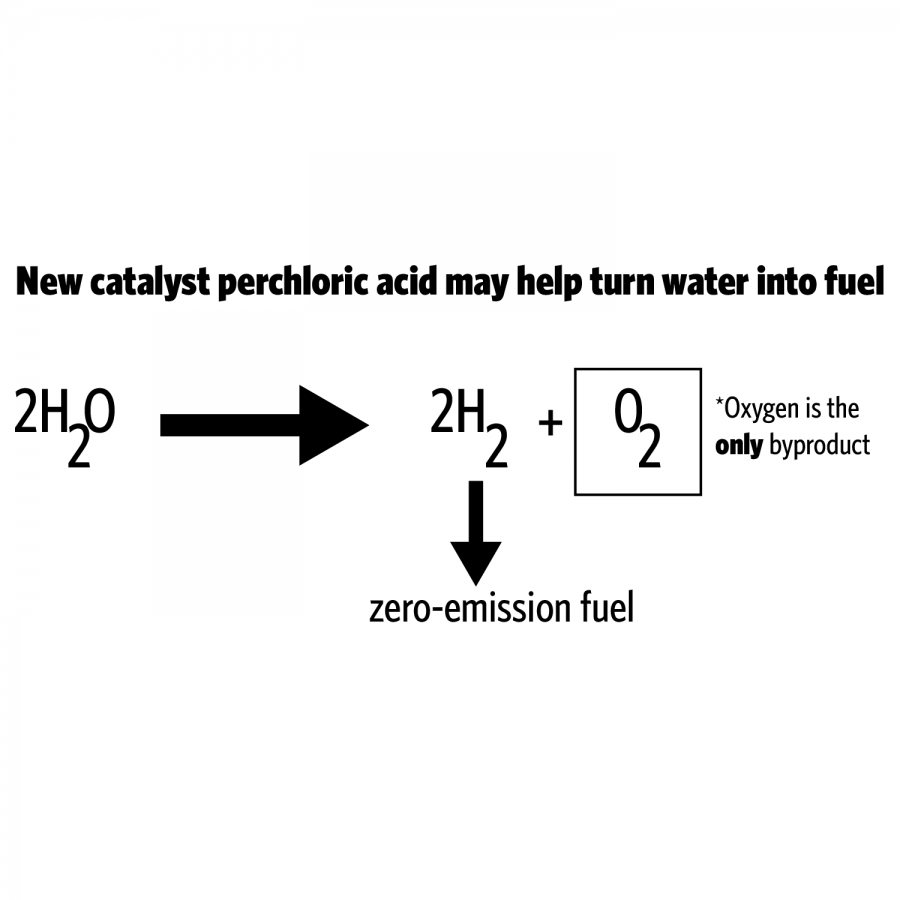

The team has found a new catalyst that expedites the rate of water-splitting reactions, which allows hydrogen to be produced faster and in larger quantities for cheaper distribution.

“Everything will be changed. Specifically, when we use a cheap material,” said Jaemin Kim, lead author of the study and postdoctoral researcher. “So, we can easily plug in this kind of catalyst. Then, it will generate hydrogen gas easily.”

Using water as the raw material to produce ecologically sustainable gas is not a new process, but the current catalysts used by researchers to break the bonds between oxygen and hydrogen, iridium oxide and ruthenium oxide are both very expensive.

This study has found a more stable and durable catalyst, which reduces production costs and increases sustainability. The catalyst is a combination of ruthenium and yttrium, which is more stable and efficient than when ruthenium is used on its own.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The higher efficiency of the new catalyst lowers the overall cost of producing the same amount of hydrogen.

Usually people use natural gas and apply heat to a catalyst to produce hydrogen, but this simultaneously produces carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and other carbon materials that are harmful for the environment, Kim said. When water is used instead, elements of hydrogen and oxygen can be produced without the carbon pieces being released.

“This research is entirely using sustainable resources, meaning water, to generate a sustainable energy source,” said Hong Yang, co-author of the study and professor in Engineering.

The study contributes to the big picture of a green technology transformation, Yang said. He hopes this new catalyst can be used to derive useful and sustainable products.

“With hydrogen having many different utilizations, it could lead to an alternative way of transportation vehicles, where cars can be fueled with water instead of gas,” he said.

The study is not yet completed, and the team ultimately strives to look for more new materials that will undergo the water-splitting process at lower costs, said Pei-Chieh Shih, graduate student in Engineering.

“We want to avoid this expensive element, but at the same time, they are the only durable materials,” Shih said.