Chemical group creates new drug catalyst

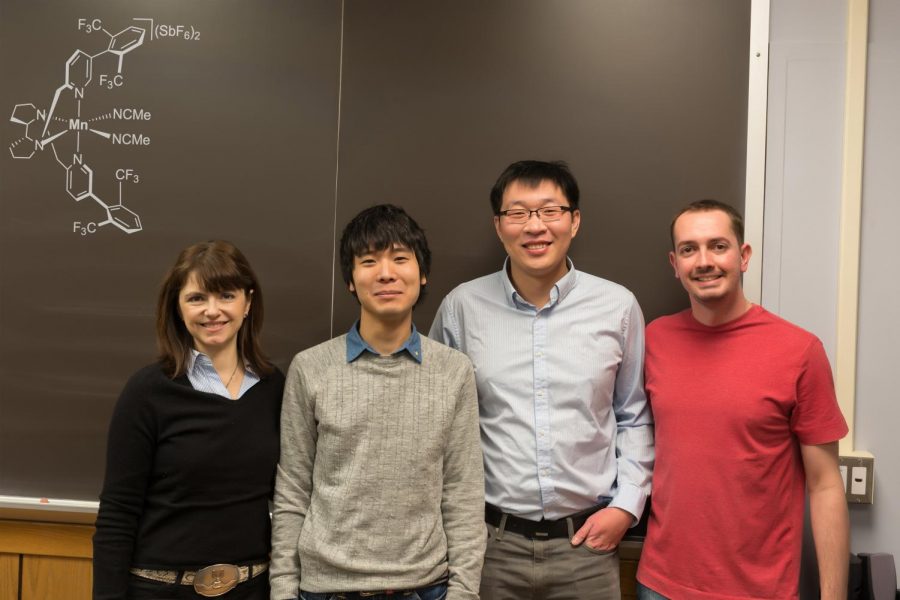

From left to right: Professor M. Christina White, Dr. Takeshi Nanjo, Jinpeng Zhao (lead author) and Dr. Emilio de Lucca Jr. The group has developed a catalyst that will change the future of medicine and pharmaceuticals.

Jan 24, 2019

A chemical research group at the University has developed a catalyst that will change the way drugs are developed by going against what were thought to be the rules of chemistry.

The White Research group works out of the Roger Adams Lab and focuses on developing synthesis-driven catalysts that are more efficient in the creation of medicine.

Jinpeng Zhao, a member of the White Research group, and two former group members, Takeshi Nanjo and Emilio C. de Lucca Jr., worked with chemistry Professor Christina White to develop the new catalyst.

“If (chemists) decide after constructing the molecule that they would like to change the hydrocarbon frame in the presence of the more reactive functionality, they often have to remake the molecule,” White said.

The newly developed catalyst can bypass the need to completely rebuild the molecule and instead focus on the strong chemical bonds that were originally supposed to be focused on after weak chemical bonds.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

White compared the creation of medicine to building a house. She said you would not build a door near where a window is, as it would possibly destroy the windows. The only option would be to rebuild the entire wall and add a door and a window.

Both Zhao and White are adamant about developing catalysts that can be used to help people and make developing medicine easier for pharmaceutical chemists.

“We always want to make our work as reachable as possible to those medicinal chemists and we want to help them to show that they can really use our system in their daily work other than just being published in the paper,” Zhao said. “We want our system to be used by other people and really make a difference.”

Nature makes the same kind of chemical reactions that this catalyst was created to perform, White said. This natural chemistry acted as an inspiration for the research on this project.

Late last year, White won an award from the American Chemical Society for Creative Work in Synthetic Chemistry for creating catalysts that drove chemical reactions that were originally only possible in nature, but can now happen synthetically.

“It turns out that nature replaces carbon-hydrogen bonds with carbon-oxygen bonds all the time, it’s happening probably right now in your body. In your liver there are these enzymes that will replace CH with CO,” White said. “So our group tries to develop artificial enzymes that will do this on these types of biologically interesting molecules.”

White described her group members as having courage for taking on problems that are both large in scope and have no obvious answer. They are the ones who perform the experiments, go over all data collected and create new ideas based on the research that they have performed.

White specifically mentioned what Zhao and his fellow researchers had done for this specific research project.

“So I guess the first thing I would say about Jinpeng, and a lot of my research group, first of all they’re attracted to solve really big problems to which there is no obvious answer in the literature and so I think it takes a very courageous person to take on that kind of endeavor,” White said. “When we started this project with Jinpeng I don’t think that either one of us has a clear idea of how to solve this problem.”

Zhao hopes that the fact that this research project has gone against the common knowledge of chemistry will inspire other fields to go against what is supposed to be true.

Even though Zhao sees the research as being targeted to chemists only, he believes performing research out of the box can be applied to other fields of science.

“What you learn in your textbook could not be true,” Zhao said. “There’s more knowledge you can bring to old paradigms.”