Research reexamines mechanism of sperm movement

Courtesy of Professor Wei Yan of University of Nevada

Professors in collaboration have found that motile cilia in the male reproductive system does not push sperm forward like previously thought, but keeps them suspended, which prevents them from collecting.

Jan 28, 2019

A new study reveals that motile cilia, organelles protruding from the surface of the cell, have a different function in the male reproductive system than previously thought.

A collaboration between University Professor Emeritus Rex Hess and professor Wei Yan of the University of Nevada examined the function of motile cilia, which extend from a cell’s surface and beat rhythmically, in the reproductive systems of mice.

“All the textbooks said that the function of the motile cilia was simply to move the sperm from the testes to the epididymis because that’s what they thought was the function of motile cilia in the female upper reproductive system,” Hess said.

In the female reproductive system, cilia capture the oocyte that is released during ovulation and move it toward the sperm so fertilization can occur, which is why textbooks assumed motile cilia had the same role in the male reproductive system, Hess said.

When conducting the experiment, Yan and his team realized cutting out only the efferent ductules caused the cilia to stop beating right away, meaning they could not be observed. Instead, they dissected the entire reproductive tract from mice to see the cilia beating.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“We took a whole lot of recordings, and when we saw them, I was surprised because my original thinking based on the textbooks was that cilia, they beat in a synchronized manner to generate this wave-like pattern, so they beat toward the same direction, in the direction of the epididymis and so the sperm, once they enter the efferent ducts, they are pushed forward by the cilia. But this is not the case,” Yan said.

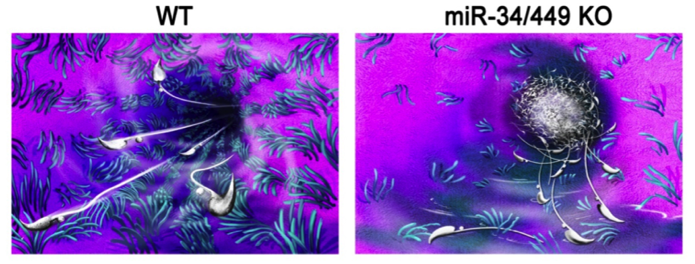

Yan found the cilia were clustered and beating in different directions, which means the cilia could not be used to push sperm forward. Instead, the motile cilia stir up the sperm and keep them suspended in a homogeneous manner, Yan said.

Removing certain portions of genes interrupted the function of the cilia in the male reproductive system.

“When they knocked out these certain microRNAs, the cilia actually then lost this ability to engage in the circular motion and what happened was that the sperm started collecting in the lumen portion of the male reproductive system,” said Cheryl Rosenfeld, professor at the University of Missouri and commentator on the paper. “It was suggested that the function was like stirring a pot, or like I talked about in the commentary, like a washing machine.

Rosenfeld likens the movement of cilia to how a washing machine moves around clothes but keeps them separate at the same time. The cilia not being able to function properly can severely damage the testes, she said.

“If you knock out the motile cilia, you cause an obstruction. You cause the sperm to form a plug, then the testes are still producing billions of sperm. They have to go somewhere and so they’re going downstream, they hit the plug, and then they back out. So you’ve got the fluid and the sperm backing up into the testes and that causes the testes to swell, and that causes atrophy of the testes,” Hess said.

If the cilia have the same function in humans as they do in mice, this may explain why some men are infertile, Yan said.

This research may be applicable to other parts of the body, not just the male reproductive system, Rosenfeld said.

In humans’ central nervous system, the brain and spinal cord, we have the same type of cilia there, and it just would be interesting if they are engaging in similar motion, Rosenfeld said.

“Even if the testes are perfectly normal, infertility is because the sperm is clogged in the efferent ducts, which nobody ever thought about, which is why I think this is going to be revolutionary if we find in humans that the efferent duct obstruction happens,” Yan said. “The problem is that right now, all the clinicians, they have no idea. They don’t even know this structure, and even if they know this structure, they have never thought about it.”