We live in the age of social media. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok and dating apps are essential in navigating our daily lives.

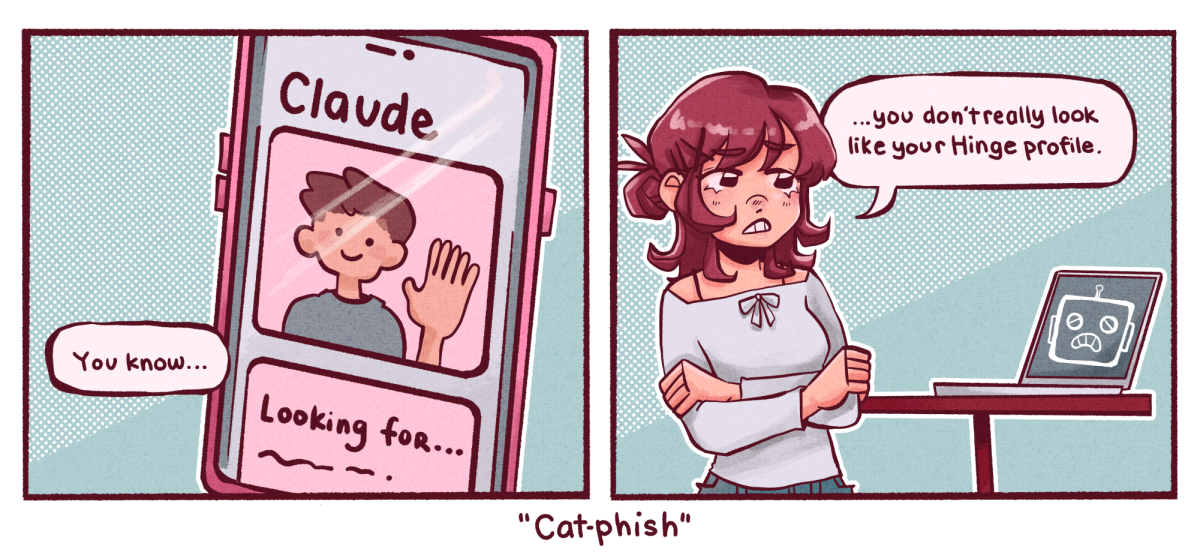

We post our successes, failures and all the in-betweens, but somewhere along this surge of online interaction arose the catfishing problem — creating a fake online identity and using it to trick and control others.

Books, TV series and online storyboards are devoted to understanding this phenomenon. Somehow, catfishing remains one of the most mysterious issues on social media. For many, these stories are anything but entertainment — they’re real life, and the consequences are devastating.

Danielle Knafo, clinical psychologist, psychoanalyst and professor at New York University, helped explain why people catfish in her 2021 article, “Digital Desire and the Cyber Imposter: A Psychoanalytic Reflection on Catfishing.”

“The phenomenon of catfishing, the adoption of a false online identity for romantic purposes or trickery, is a laboratory in which self-creating in the virtual world plays out in real time,” Knafo wrote.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

For Noah Frederking, sophomore in Business, online deception is a topic all too familiar. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Frederking believed he was communicating on Snapchat with a girl from a nearby town. The online relationship lasted months, during which they exchanged Snapchat messages, texts and intimate conversations. A few months later, he discovered the person he thought he knew didn’t exist.

In fact, it wasn’t just one person deceiving him, but two. What started as a playful online conversation quickly took a turn for the worse and ended in exploitation.

“I remember the last night we were actually talking,” Frederking said. “I got a Snapchat, and it wasn’t from the person I thought it was. It was from two people, and the Snapchat just said, ‘Gotcha.’ Then, I was blocked. I had no time to react.”

Knafo said people who decide to catfish often have low self-esteem and extreme insecurity, using social media to portray themselves as someone they like more than themself.

Catfishers believe that by presenting themselves a certain way online, they’ll receive more validation and attention. In some cases, this works. But healthy, long-term relationships are not based on lies.

Kitty DeHaan, sophomore in LAS, shared her friend’s experience with a catfisher in high school.

“He started talking to (the catfisher) and was totally under the assumption that she was this random, pretty girl that was trying to get attention from him,” DeHaan said. “Turns out it was just this crazy girl that was flirting with him a lot.”

DeHaan, the catfisher and the victim have been acquaintances since middle school. According to DeHaan, the catfisher, now a college ballet dancer, had a reputation for dishonesty.

“I don’t know, specifically, who else was affected, but she was definitely known, in general, to pull stunts like this,” DeHaan said. “There were a couple of stories of her exposing personal photos of a friend of hers, exposing people in general and doing manipulative things in order to get information that she wanted.”

DeHaan’s story aligns with Knafo’s description of catfish behavior. Knafo also states that narcissism, a trait encompassing features like selfishness, lack of empathy and the need for admiration, is common in catfishers. The online praise catfishers receive outweighs the negative impact of their actions despite the gratification coming from an elaborate fantasy.

In the case of DeHaan’s friend, the catfisher became accustomed to exploiting people through social media platforms. The catfisher was then able to manipulate people through the vulnerabilities they shared online.

Knafo explained that there are numerous reasons why catfishers take to the internet scheme. They range from low self-esteem to more sinister reasons like vengeance, humiliation or manipulation. Most of these reasons could have driven what happened to DeHaan’s friend.

Some individuals use catfishing to express themselves more authentically than how they normally act outside of the internet, Knafo wrote.

Understanding what lies beneath the surface of an online conversation can be tricky. A 2024 survey stated that 1 in 5 online dating service users lied about their age on their dating profile. Another 14% lied about their hobbies and interests, and 12% lied about their height. An additional 14% reported lying about their income.

However, posing as an entirely fake identity is different.

While catfishing may be as old as the internet, developments in artificial intelligence make the catfishing conversation increasingly relevant.

Schemes no longer require photos of real humans — people can now assume the identity of an AI-generated image. All catfishers need is the power of a computer and working Wi-Fi.

“If someone’s not willing to call you or FaceTime you, and they just kind of disappear, make sure you acknowledge the red flags,” Frederking said. “And it’s hard at the time, it really is. If I could go back and tell my younger self something to save myself a lot of stress, it would be, ‘You’re not a criminal; you’re the victim, so remember, it’s OK to talk about it.’”

As long as the internet continues to evolve, catfishers will continue to strike. Prioritizing authentic, face-to-face interaction and more thorough online safety can put an end to catfishing.