Last updated on July 3, 2024 at 10:29 a.m.

For 13 days last semester, pro-Palestine supporters set up encampments — first at Alma Mater, then on the Main Quad — to demand the University cut ties with companies profiting from the war in Gaza.

These protesters are not alone. Student bodies at over 100 colleges in 30 states around the country have pressured their administration to be held accountable for their investments as well as partnerships with Israel.

On Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups launched a surprise invasion of southern Israel, killing 1,200 Israelis and abducting 250. In Israel’s subsequent bombing campaign and invasion of Gaza, the military has killed 36,000 Palestinians, with over 1.7 million internally displaced, and the enclave is also facing a severe food and humanitarian crisis, according to the United Nations.

In January, the International Court of Justice ordered Israel to take measures to prevent genocide in Gaza. Eight months into the war, the International Criminal Court now seeks arrest warrants for war crimes against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Defense Minister Yoav Gallant and Hamas leadership.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

On April 28, Students for Justice in Palestine at the University published a list of demands on their Instagram. They asked the administration to divest from corporations profiting from the occupation of Palestine, cease collaborations with corporations involved in the oppression of Palestinians and publicly disclose all of its financial assets.

So, what do these calls for divestment mean and what would potential divestment look like?

The University is well endowed

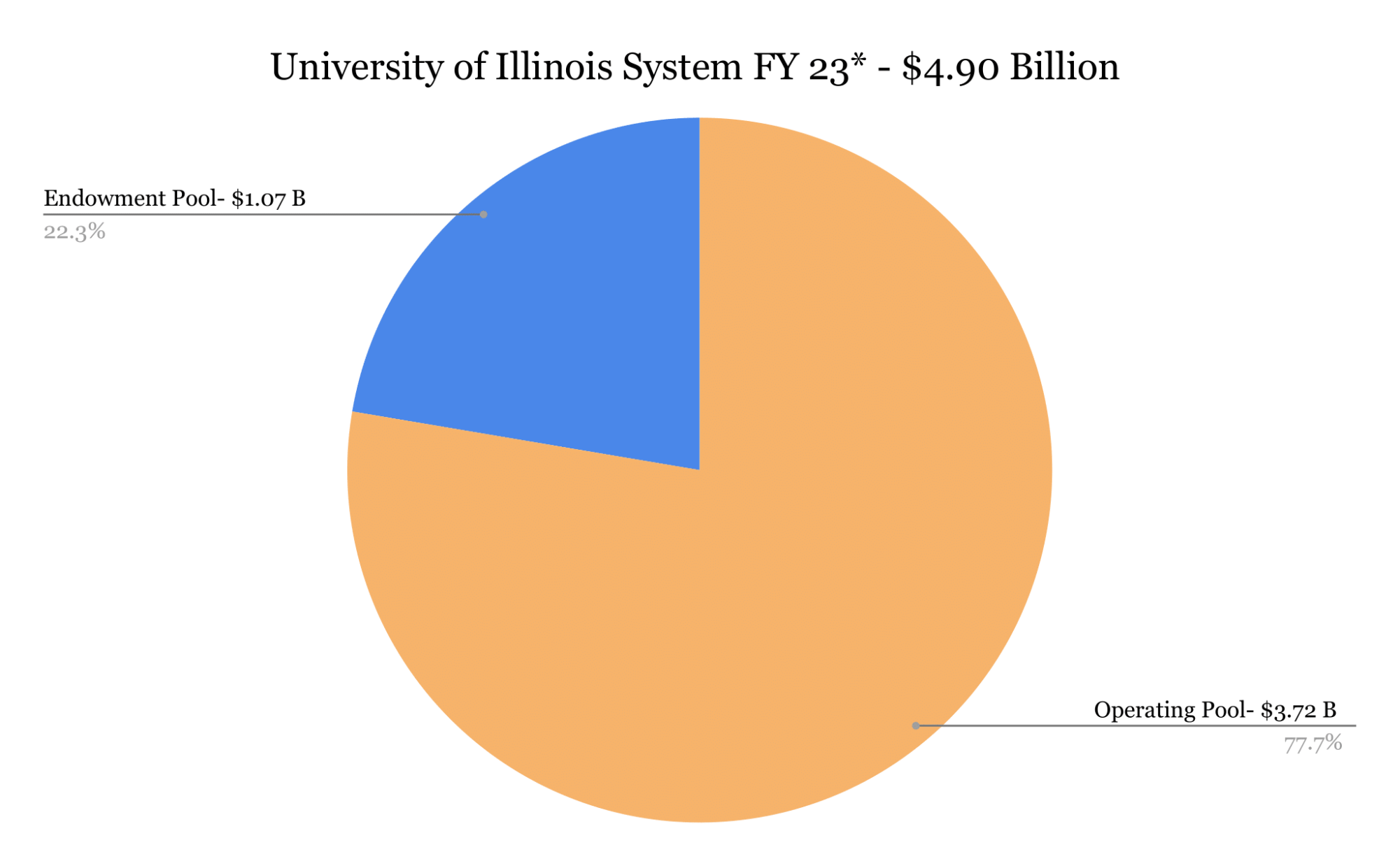

The University has two large pools of money: the University of Illinois System and the University of Illinois Foundation.

University of Illinois System

The first, the University of Illinois System, holds $4.9 billion in assets as of fiscal year 2023. This $4.9 billion is split into the Operating Pool and the Endowment Pool. The Operating Pool — composed of revenue from tuition, state funding and grants — makes up $3.72 billion, and the Endowment Pool — worth $1.07 billion — comes from private gifts and donations.

UIS is managed by a board of trustees, who set investment policies and appoint members to oversee committees such as the audit, budget, finance and facilities committees. The UIS is a public body, and information about the UIS’s portfolio was obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

University of Illinois Foundation

The second pool, the University of Illinois Foundation, serves as the fundraising and private gift-receiving organization of the University. In 2023, UIF had an endowment worth $2.73 billion. However, unlike UIS, the UIF is not a public body under the FOIA and the exact contents of the organization’s investments are unknown.

Institutional ties to the war in Gaza and Israel

Money Out

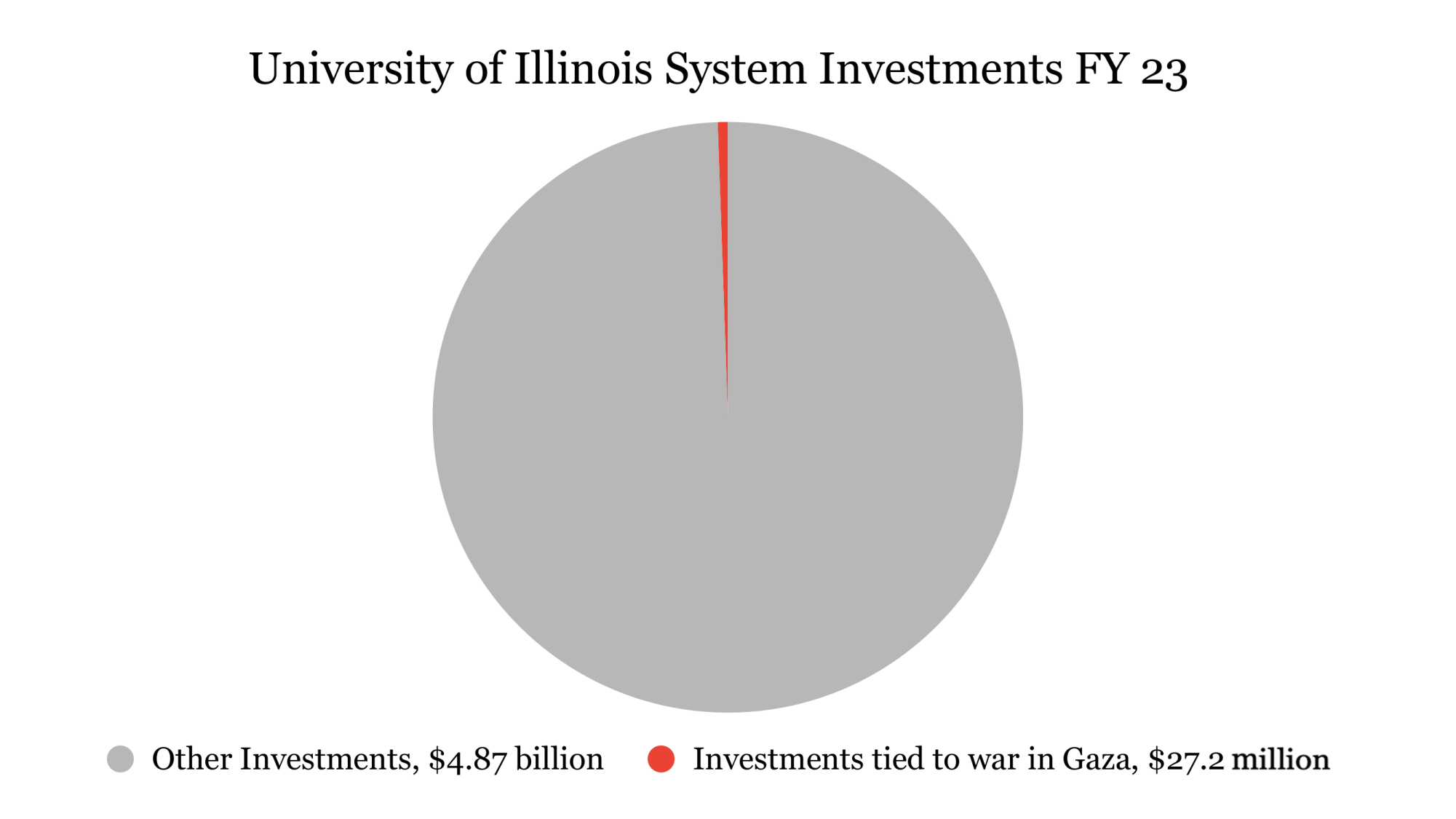

The UIS portfolio held $21.3 million in assets tied to companies involved in the war in Gaza and Israel in fiscal year 2023. These assets consisted of investments in the following companies.

- $20.3 million in BAE Systems PLC., Boeing Co., Northrup Grumman Co., Caterpillar Inc. and Lockheed Martin Co. These companies are present on the Action Center for Corporate Accountability’s divestment list of publicly traded companies that “enable or facilitate human rights violations or violations of international law” in Gaza.

- $443,000 in State of Israel securities in the form of a corporate bond and an international government bond.

- $643,000 in Expedia Group, linked to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in a 2020 report by the United Nations.

Much of the UIS’s money is placed in the hands of third parties. These external managers, known as asset management companies, set and manage their own investment funds.

Most notably, UIS invested a total of approximately $387 million in two funds managed by BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest asset manager. These two funds were the ACS US ESG Insights Equity Fund, in which the UIS invested $228 million, and the ACS World ESG Insights Equity Fund, which holds the other $159 million.

According to BlackRock’s website, the engine manufacturer GE Aerospace represents 1.56% of total holdings in the US EGS Insights Fund and 1.42% of total holdings in the World ESG Insights Fund.

The U.S. Department of Defense awarded a $684 million contract to GE Aerospace, the legal successor to General Electric, to manufacture helicopter engines for the U.S. Navy and Israeli military in 2023.

Thus, the 2023 UIS portfolio holds at least an additional $5.8 million, related to war in Gaza, managed by BlackRock. Combined, there is a sum of $27.2 million in University investments linked to the war in Gaza and Israel in FY 23. This number is a lower bound and excludes any investments in the UIF portfolio.

Money In

University connections to some of the previously mentioned companies also extend beyond institutional investments by UIS. Several of these companies support the University through donations, projects and academic programs.

According to their website, the Grainger College of Engineering’s industry partners include Boeing, Caterpillar and RTX Co. (formerly known as Raytheon Technologies Co.). In 2023, Boeing — one of the world’s largest defense contractors — pledged $300,000 over the next three years in support of the Center for Sustainable Aviation at the University.

Caterpillar, which has supplied armored bulldozers to Israel for decades, operates a satellite office based out of Research Park. Last November, the Champaign-Urbana chapter of the Party for Socialism and Liberation organized a student and worker demonstration at the Caterpillar office in support of Palestine.

What calls for “divestment” really mean

Given the complexities behind University investments and multilateral links to companies involved in the war, what does divestment mean — both as an idea and a realistic course of action?

In itself, divestment is the act of selling off shares and stopping future investments in specific companies or a sector.

“Basically, you’re selling the current holdings you have, you’re restricting new investments … and you’re doing it in a manner that continues to meet your fund’s investment return targets,” said Dan Cohn, energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Reasons for divesting can vary, but it is often to achieve a political, social or ethical goal. Alternatively, it can be for purely financial reasons. For example, Cohn said the movement to divest from the fossil fuel industry uses not only a moral argument against climate change but also an economic one.

“The fossil fuel sector is no longer producing the kinds of financial returns for investment portfolios that it once did, and when you take a serious look at its future, the future looks pretty limited,” Cohn said. “We see divestment as being a practical way to limit endowment losses from fossil fuels.”

Illinois Rep. Abdulnasser Rashid, the first Palestinian-American elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, pointed out that divestment is very targeted, citing Lockheed Martin as one instance.

“One example is a university’s endowment investing in Lockheed Martin, a weapons manufacturer which is very much aware that Israel is using … its weapons to commit war crimes — yet it’s still supplying Israel with those weapons,” Rashid said. “A divestment call says that the University’s endowments should not be investing in Lockheed Martin and it is as straightforward as that.”

Divestment from the war in Gaza is primarily based on ethical grounds — supporters say the University has a moral impetus to cease financially supporting companies complicit in genocide.

On May 10, Students for Justice in Palestine and Faculty for Justice in Palestine released a joint statement in which they argued this idea. According to the statement “The U of I System puts millions of dollars into the Israeli war machine and refuses to acknowledge it. The U of I System must be held accountable for its complicity in the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the occupation of Palestine.”

Yet, divestment is not as clear-cut in execution.

Challenges to divestment

The Board of Trustees, in charge of the UIS portfolio, is a fiduciary body and is responsible for the system as a whole, per their website. Thus, calls for divestment can conflict with the financial interests of the University.

“Divestment by its nature undermines the diversity of investments,” said University College of Law Professor Lesley Wexler over email. “With the nature of modern investments, it often means selling not just stock in a single company, but getting out of a fund that incorporates hundreds of companies — only some of which might be ones that students wish to divest from.”

George Taylor, sophomore in FAA, is a member of Students for Environmental Concerns and a pro-Palestinian supporter who acknowledged these difficulties. He compared the two ongoing divestment movements at the University.

“With the fight to divest from fossil fuels, there are very specific companies … we could identify and then pose alternatives to,” Taylor said. “But with the war effort, we can divest from all the small companies that we want … but we’ll still be giving money to Blackrock, and Blackrock is gonna give money back to those (companies).”

Divestment from the war in Gaza also faces legal challenges.

Known as anti-boycott, divest and sanction laws, these policies aim to take action against boycotts of Israel. Illinois’ anti-BDS law, the first of its kind passed in 2015, applies to the state pension system.

“The Illinois retirement system must sell (redeem, divest or withdraw) all direct holdings of companies identified by the Illinois Investment Policy Board and it may not acquire securities of restricted companies,” Wexler said. “In other words, the Illinois pension system can’t invest in companies that are engaged in boycott activities towards Israel.”

Anti-BDS laws also vary from state to state. For example, in Ohio, Revised Code Section 9.76 prevents state agencies from contracting with companies that divest from Israel. Therefore, per the Columbus Dispatch, Ohio State University legally cannot divest from Israel.

However, these financial and legal challenges have not impeded schools around the country from divesting.

Other schools have divested, and so has UI (in the past)

Several other universities have agreed to take steps towards potential divestment, typically in return for student encampments shutting down.

On April 30, Brown University became one of the first major universities to come to an agreement with protestors, with the Office of the President releasing a statement that declared Brown would act in two ways. First, the university would hear students’ concerns about divestment at a corporate meeting in May. Second, and more significantly, the Office of the President asked the school’s Advisory Committee on University Resources Management to write a divestment recommendation to be put to a vote in October.

“The students and administration agreed that I will ask the Advisory Committee on University Resources Management (ACURM) to provide me with a recommendation on the matter of divestment by September 30, 2024, and this will be brought to the Corporation for a vote at the October 2024 Corporation meeting,” the statement said.

Similarly, the University of Minnesota agreed to hear students at a board meeting and make their investments more transparent — again in return for their encampment closing. The Evergreen State College in Washington declared they would explore potential divestment by creating a committee of students and faculty tasked with reviewing investment policies.

Union Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Columbia University in New York, became the first school to adopt a divestment plan when, on May 9, the Board of Trustees endorsed policies by Union’s investment committees that directly target investments in Israel.

According to a statement by Union, the policies include “revising the section of our investment policy statement section pertaining to responsible investing to include an overt reference to the Israel-Palestine hostilities, in addition to current robust policies regarding fossil fuels, military weapons, private prisons, etc.”

The policies also target Union’s externally managed investment, with Union “directing our investment managers to exclude those companies from the portfolios managed on behalf of Union.”

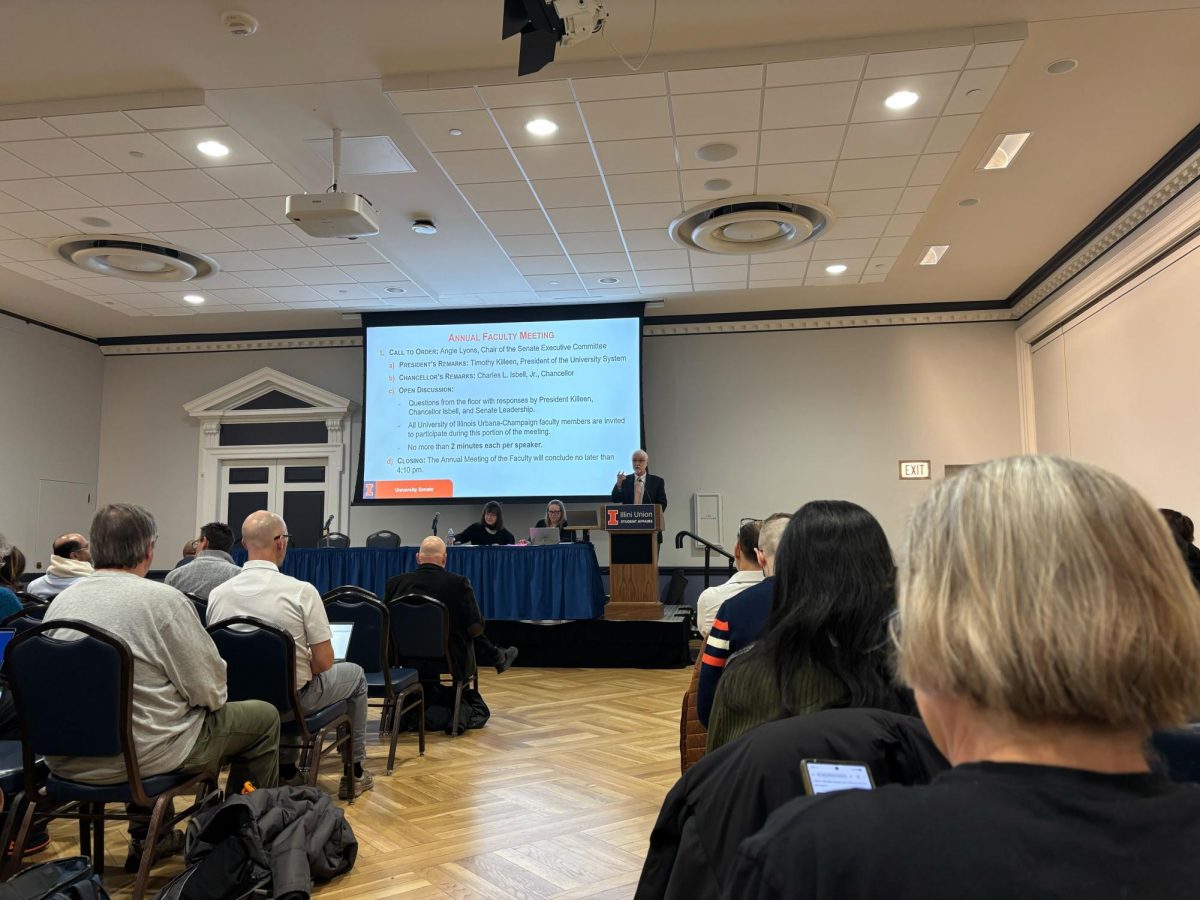

While there have been discussions between protestors and the University of Illinois administration last semester, they have not reached any agreements to divest. But the University of Illinois has divested in the past.

In the 1980s, there was a large push for divestment from companies profiting from apartheid in South Africa. Protesters built a shantytown on the Main Quad, staged mock riots and sent out postcards calling for the release of South African political prisoners.

In 1987, after having defeated previous motions, the Board of Trustees agreed to divest, however, the move was largely viewed as symbolic, as the total divested was just $3.3 million.

What then, would divestment actually accomplish?

In this context, Rashid said he believes divesting even a small amount of money can snowball into a much larger effect.

“Three million here and 10 million there and 100 million here — it will add up and will have an impact economically and financially on the companies that are being divested from such that they change their policies and no longer supply Israeli weapons,” Rashid said.

Rashid added students and grassroots movements calling for divestment make a tangible difference beyond the finances.

“They’re educating so many people about what’s happening and what has been happening to Palestinians for decades, and that itself is a major victory (to help) change the hearts and minds of generations of people,” Rashid said.

Institutional divestment also sends a signal to the rest of the market in general, Cohn noted.

“There’s people who say when you (divest), institutional investors are basically telling the rest of the market this company is not that creditworthy, and I think that’s true,” Cohn said.

Looking ahead

Beyond the University’s financial priorities and potential legal issues, creating a comprehensive divestment policy plan is not a simple task.

“It requires some due diligence to make a specific plan and it requires some deliberation about that plan to make sure it’s done right,” Cohn said, speaking broadly on divestment.

Still, if the University plans to divest — as many hope it will — it will have examples from other major universities and its own history of divestment as reference.

For now, Rashid, who visited the encampment at the University with fellow Illinois Rep. Carol Ammons, emphasized the need for transparency and dialogue between protestors and University administration.

“I encourage the students, faculty, administrators and trustees at the University to work together in good faith to make sure that the investment of the University … are in line with their values,” Rashid said. “There should be real engagement by those who are in decision-making positions with the students and the faculty who are asking for divestment.”