Last updated on Sept. 30, 2024 at 05:00 p.m.

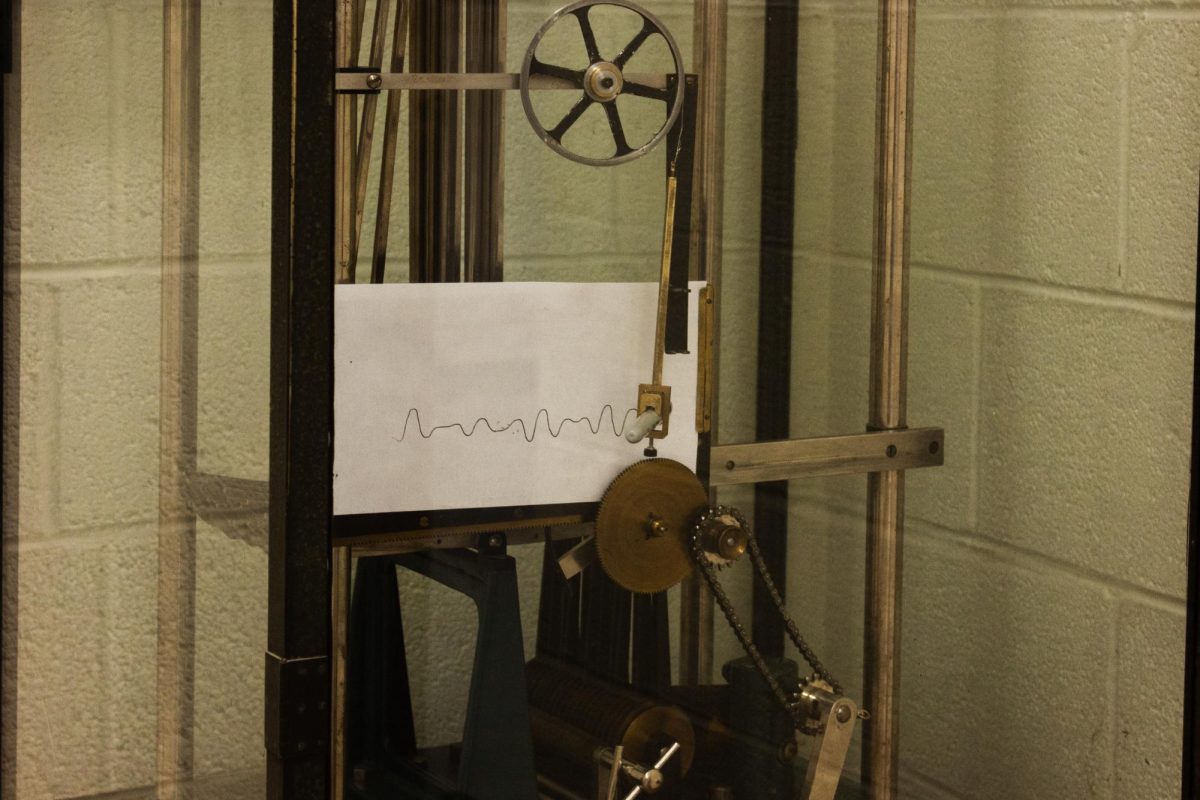

The harmonic analyzer is a historic mathematical instrument housed in Altgeld Hall that has been performing a mathematical technique called Fourier Analysis since its creation in 1897.

Speaker Maria de Lourdes Ortega Mendez, member of the Gutenberg Research College, came to the University to discuss the over 100-year-old Altgeld Analyzer, one of the only operational analyzers left in the country.

Fourier analysis is used to manage bandwidth for phone networks and audio compression to make audio files easy to send. It was also used to analyze the wavelengths of colors.

Mendez talked about the history of these harmonic analyzers on the first day of the Harmonic Analysis and Differential Equations, also known as HADES, seminar. This series of talks covered how the topic of differential equations varies by field. Some talks had to do with the history of important machines and the field’s application within the physical sciences.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

She said that two people were responsible for creating the machine: Professors Albert A. Michelson and Samuel W. Stratton.

Albert Abraham Michelson was a German-American physicist whose main field of study was measuring the speed of light. As a result of his work, he was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant to teach at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, making him the first American to win the prize.

“He went to Washington to see the president because everybody was believing in this young man, but he didn’t get the information,” Mendez said. “So President Grant used an exception and sent him over and I think we can agree … he did something good with that.”

In 1897, Michelson made the first harmonic analyzer prototype, where the machine carried 20 gears originally. This machine is the harmonic analyzer in Altgeld Hall today.

Samuel Wesley Stratton was a physicist, similar to Michelson, and held administrative positions in the American government. Stratton was also an alumnus of the University and kept good relations with the University over time as he developed his career.

“Stratton received a letter from the College of Engineering congratulating him on his new appointment as the president of the world standard,” Mendez said. “They are proud of him and they also say it will be to visit the University. So they tried to stay in touch with him.”

Michelson and Stratton then met at the University of Chicago and worked together to make a more finished version of the harmonic analyzer in 1898 with 80 gears instead of the prototype’s 20.

Mendez said the machine is made of gears, springs and levers. The cams and rocker arms interfere with the machine depending on how far the machine is rotated. As a result, the waves modeled from the machine are drawn out.

One member of the audience asked Mendez how someone using the machine would calculate how many squares were down there under the graph made.

“So counting the squares is the way to do the calculation,” Mendez replied. “The problem is wondering which ones were there. Because I don’t see any kind of point or anything? And how does he escalate them? What numbers did he put into the machine? So that’s what I’m finding out right now.”

Mendez said the main differences between the machine in Champaign and Chicago are the number of gears each machine has and the condition. Mendez said the machine in Altgeld was in good condition, while the machine in Chicago had missing parts.

For more of an in-depth analysis of the harmonic analyzer, as well as the mathematical technique used, visit Engineering professor Bill Hammock’s website, where he explains the machine in short videos.