Illinois’ public universities have the third highest average in-state tuition in 2021 nationwide, with the average cost of in-state tuition at around $15,000, per Education Data.

Dylan Sharkey, assistant editor at the Illinois Policy Institute, a nonprofit research organization that aims to represent taxpayers in the state, said the number reflects not just the University of Illinois System, but the average of all public universities in the state.

“We’re up there — the highest in the Midwest and third highest in the nation. It would be one thing if we had the third best public universities in the nation, but if you look at US News and World Report rankings, (Illinois universities on average) are out of the top 15,” Sharkey said. “So (this) kind of leads to the fact that for some schools, people are paying more and getting less in terms of quality education.”

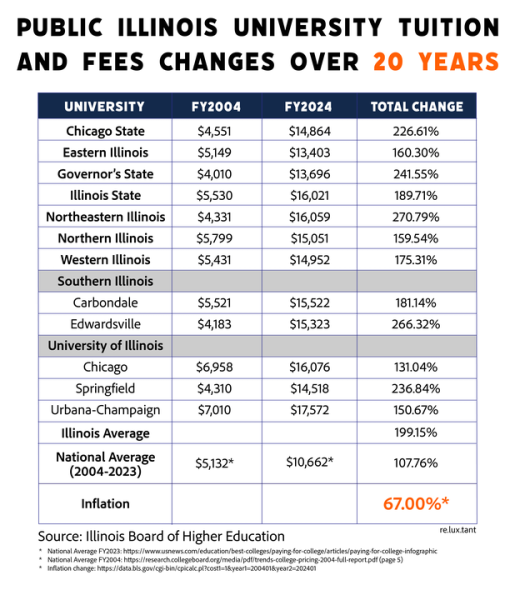

Although rising tuition and fees reflect a nationwide trend, tuition growth at Illinois universities has outpaced the national average. According to data from the Illinois Board of Higher Education, tuition and fees at all Illinois colleges have on average almost tripled between 2004 and 2024.

Nationally, however, the average tuition and fee cost at a four-year public university approximately doubled from 2004 to 2023.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Both Illinois tuition and national tuition changes surpass inflation over the same period. According to the Consumer Price Index, which tracks the increase in prices of common household goods, cumulative inflation over the same 20-year period was only about 67%.

Support from the state has declined, University of Illinois System as a case study

At the University of Illinois System, which consists of the Chicago, Springfield and Urbana-Champaign campuses, tuition at each institution is set annually by the Board of Trustees.

Tuition is based upon a number of factors, including instructional costs, state funding and the rate of inflation, according to the UIS website. However, UIS has seen fluctuations and decreases in direct state support in recent decades.

“The state spent approximately $9,310 less per University of Illinois student in (the fiscal year) 2022 than it did in FY 2000 when accounting for the impact of inflation and for changes in the mix of students enrolled,” according to the UIS Tuition Book released for FY 2024.

William Bernhard, interim associate chancellor and vice provost for budget and resource planning at the Urbana-Champaign campus, said declining state support is not isolated to Illinois.

“This is a trend nationally in American higher education where the states have … reduced their support for higher education, or it hasn’t kept up with inflation,” Bernhard said.

He noted though that in the mid-2010s, universities in Illinois received little state funding due to a budget standoff. From 2015 to 2017, then-Gov. Bruce Rauner and former Speaker Michael Madigan disagreed on the state’s budget.

“I think the only thing that might be unique is the budget impasse in 2015 when Gov. Rauner and Speaker Madigan had played chicken with a budget and never appropriated anything,” Bernhard said.

Pension spending has also impacted funding for higher education.

In 2023, Illinois had over $140 million in unfunded liabilities toward pensions. In other words, the state does not have an adequate amount of money set aside to pay the full expected cost of what they promised employees.

“(Pensions) eat up a much bigger, bigger chunk of the pie, so to speak, than it did 20 years ago,” Sharkey said. “From fiscal year 2000 to 2022, pension spending rose by about 584%, while total spending was up 21%. Rising pension costs crowds out funding that could go to operating budgets for universities.”

To fund costs, universities have to place a greater emphasis on tuition as a source of revenue, said David Merriman, professor of public administration at the University of Illinois-Chicago and leader at the UIS Institute of Government and Public Affairs.

“When (state) appropriations go down or don’t keep pace with inflation, then the university needs to have other mechanisms to raise funding, and often that is tuition,” Merriman said.

However, Merriman also pointed out that the state does pick up a good amount of employee costs by making payments on behalf of UIS toward benefits and pensions.

“The state not only makes appropriations for spending in general, but also particularly covers most of the cost of employee benefits, and … in particular, that’s retirement benefits and healthcare benefits,” Merriman said.

University budgets have changed

Increased tuition rates can reflect changing budget priorities, said Bernhard. The University has moved from a low tuition, low financial aid and high state support institution to a high tuition, high financial aid and low state support institution.

“We increased tuition a lot in the early 2000s and we have tried to offset that with financial aid, which targets students with need,” Bernhard said. “And we now … devote about $135 million each year to centrally budgeted financial aid.”

Revenue growth has also been used to support increasingly larger administrative costs, according to an Illinois Senate Democratic Caucus investigation on executive compensation in 2015.

“While tuition at Illinois’ public institutions has skyrocketed, so has executive compensation,” the investigation found. “This report finds that tuition increases have coincided with a dramatic increase in administrative costs, including the size of administrative departments and compensation packages for executives.”

Illinois Commitment, scholarships hope to ease financial burden on students

Sharkey, who attended high school in Illinois and college in Iowa, said high in-state tuition incentivizes young people to leave the state.

“I think that’s the worst group of people you could levy debt onto because it’s their youngest point,” Sharkey said. “I’ve known so many people in my high school who were ready to leave, and I don’t blame them because it made financial sense.”

To mitigate the cost of attendance, the University offers a wide variety of scholarships, grants and programs such as the Illinois Promise and Illinois Commitment.

“Tuition decisions are made in relationship to financial aid policy and resources, with the goal of minimizing financial barriers for all admitted students,” according to the FY24 Tuition Book.

However, Sharkey pointed out that it’s unrealistic to expect students to fully fund their education via scholarships or grants.

“Governor Pritzker has talked about more MAP grants (and) scholarship opportunities, which is great,” Sharkey said. “I think it’s hard to expect a student to just do all this research, on top of applying to a school, to get the most money they can get from scholarships and grants.”

Maya Bielas, junior in LAS, is one recipient of the Illinois Commitment scholarship, which waives tuition and fees for Illinois residents whose families make below $67,100 annually.

“This is the only way that I probably would have been able to get away with a full four-year university — not only that — but I’m managing to do a dual degree too,” Bielas said. “I’m not tanking my family’s wallet by actually getting an education and setting myself up for my future.”