A new study from the University found that wetlands in the Mississippi River Basin effectively filter nitrogen runoff from bodies of water, saving municipalities thousands in filtration costs per year.

When excess nitrogen is left on the surfaces of crops, precipitation events can cause the nitrogen to run off into nearby ponds or streams. This pollution leads to hypoxia and algal blooms in water sources, both of which are associated with deaths of marine life and overall decreased water quality.

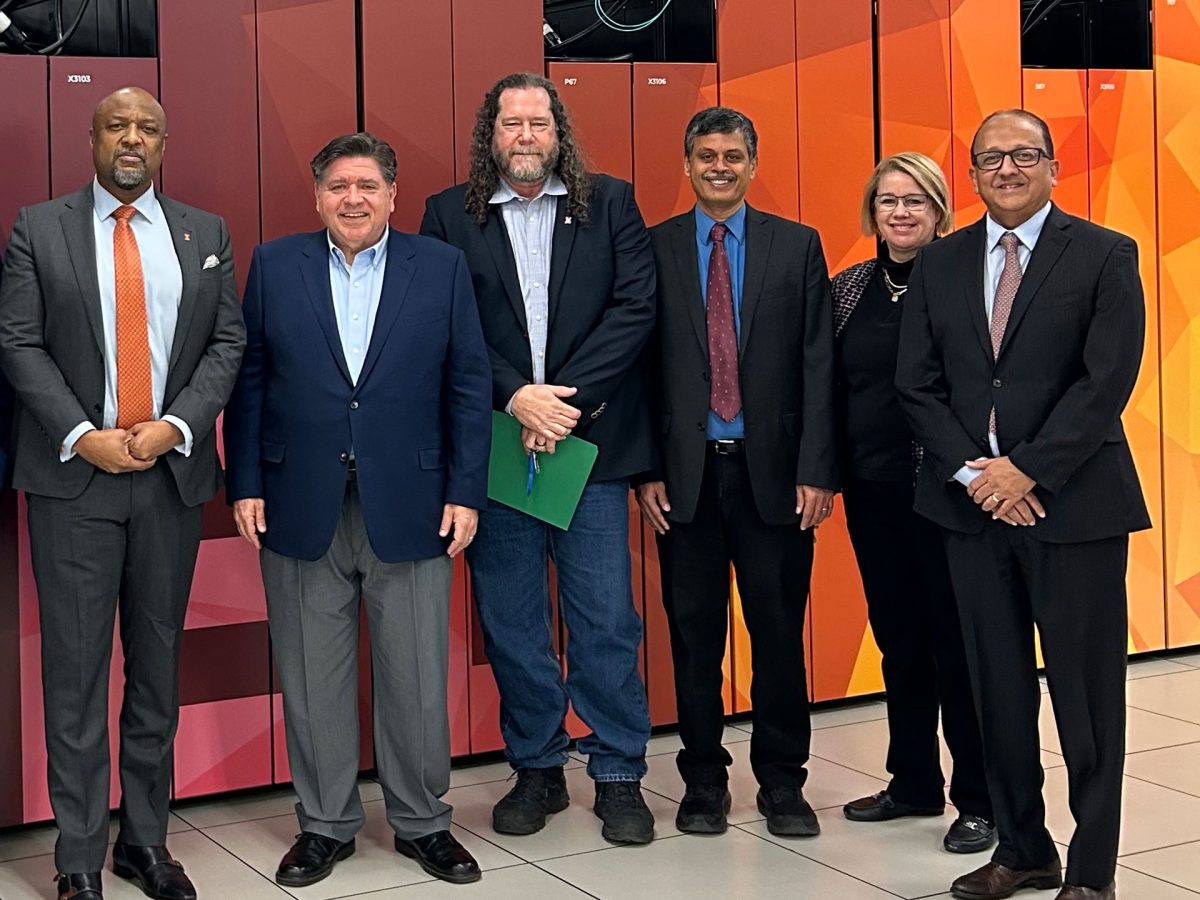

Marin Skidmore, professor in ACES, published the study in collaboration with Montana State University professor and researcher Nicole Karwowski.

“In the same way that your kidneys pull toxins out of your body and release them, wetlands can do that with nitrogen,” Skidmore said. “Wetlands are also equated to sponges, because under high precipitation events, they absorb a ton of water, so they can actually prevent flooding downstream.”

Wetlands are defined as areas where water covers the soil for at least part of the year. The presence of water creates specially adapted soils and provides habitats for a variety of wildlife.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The pair used 30 years of data from the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, formerly known as the Wetland Reserve Program, to measure the filtration abilities of wetlands.

In the program, farmers whose land sits on converted wetlands can be compensated for giving up part of their land to be restored to its natural state, creating an area known as an easement. Skidmore and Karwowski studied wetland easements along the Mississippi River Basin — a region that encompasses 40% of the conterminous United States, according to their study.

The researchers measured the filtration of three nutrients: phosphorus, ammonia and total Kjeldahl nitrogen — a measure of combined ammonia and organic nitrogen. Like nitrogen, ammonia and phosphorus can act as harmful pollutants and cause eutrophication — harmful algal blooms — in water.

They found that wetland restoration reduced ammonia in water by 62% and total Kjeldahl nitrogen by 37%. Restoration did not have a significant impact on phosphorus levels, as wetland plants can store phosphorus effectively, but not filter it out of water completely.

“One of the things that we were worried about is that, if there’s too much nitrogen coming into the wetland, the wetland could be overwhelmed,” Skidmore said. “We actually find that the wetland easements perform equally as well, or maybe even a little better in areas with a lot of agriculture.”

Skidmore said this finding is especially promising for Illinois, where crop production is widespread but poses high risks for nitrogen runoff.

The study also found that wetlands help municipalities save money on water treatment due to their effective filtration abilities.

For small utilities, a 100-acre wetland restoration can save $1,289 in treatment costs. For medium-sized utilities, the same plot of restored wetlands could save over $17,000 per year.

“The wetlands are really cost-effective because the local communities have to spend less on water treatment,” Skidmore said. “You spend money restoring the wetlands, but you save money by having cleaner water.”

Skidmore said she wasn’t aware of any other studies of comparable size and depth.

“I believe that our study is the first of its kind and scale,” Skidmore said. “We’re looking at 30 years of data and really large geography. I have not seen any that do the same thing.”

As the wetlands Skidmore studied were restored, they are not included in the 72% of Illinois wetlands recently found to be unprotected from development. She said she predicts increases in surface water nitrogen levels near wetlands that are converted to agriculture, following the recent removal of protections.

Skidmore said she was glad to examine the ACEP’s effectiveness, as many similar programs don’t receive these tests.

“Being able to communicate to federal policy makers, to the American public, the tax dollars that go to this program are getting a return … I think is part of my role as an economist,” Skidmore said.