A University professor has recently made progress towards developing a treatment for former alcohol consumers with liver disease.

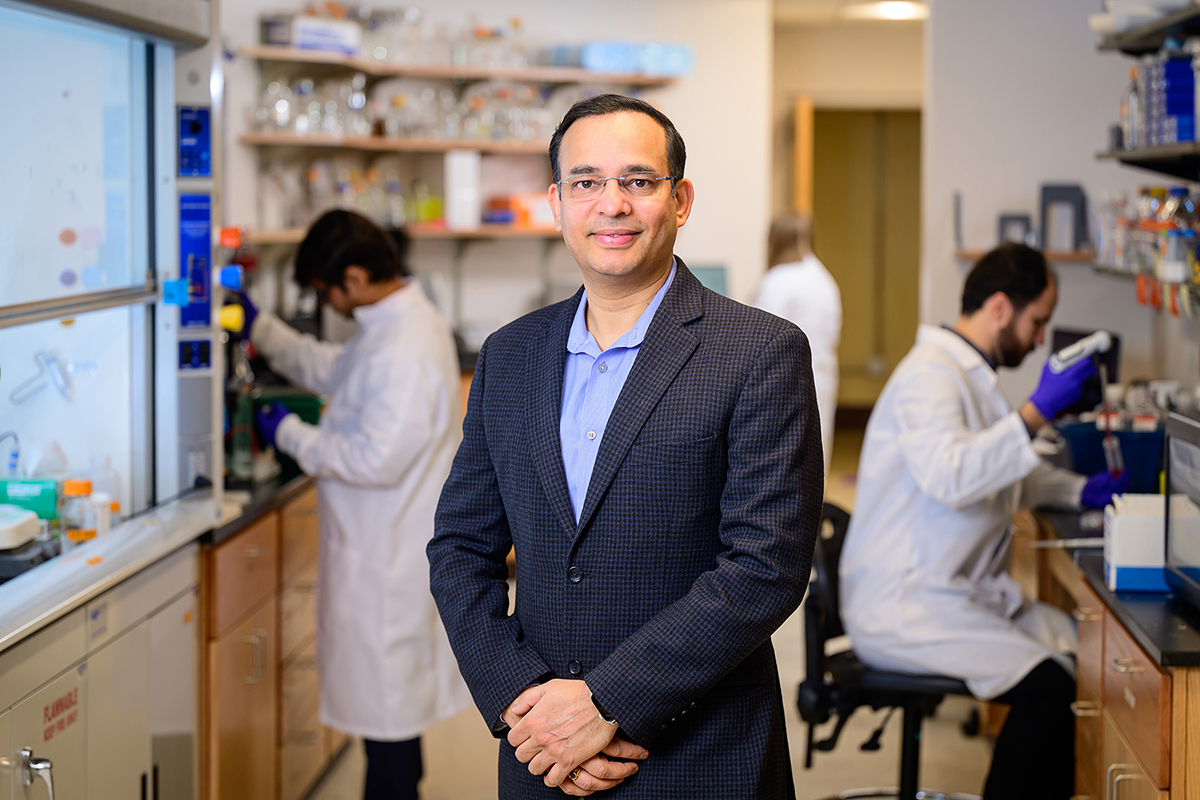

Auinash Kalsotra, an RNA researcher and professor in LAS, and Anna Mae Diehl, a professor at Duke University School of Medicine, collaborated on the study to answer why liver cells do not regenerate in liver disease patients — even after they stop drinking.

The liver has the unique ability to regenerate to its normal size, but loses that ability in liver disease patients and from prolonged excessive drinking.

The researchers published their findings in Nature Communications on Sept. 10 and made progress in answering a longstanding question. Their findings revealed that liver cells fail to regenerate because RNA — a nucleic acid that helps generate proteins — is misprocessed during protein making due to alcohol consumption, resulting in cells getting stuck between regenerating and functioning.

Kalsotra spoke to The Daily Illini about his findings and what motivated him to look further into the lack of liver cell regeneration. He referenced the increase in liver disease over the past 20 years compared to other diseases as the main reason for his research.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“The number (for liver disease) has gotten worse,” Kalsotra said. “Every other disease, like diabetes, cancer and heart disease has decreased because people are trying to work on that. What’s happening to the liver tells us that this is a serious problem. The question is, when a liver has such a capacity to regenerate, why is it failing?”

Over the past five years, Kalsotra and his team narrowed down why RNA gets misprocessed in liver disease patients. While liver cells jump between fetal and adult states in healthy regeneration, the team discovered the cells remain in limbo when trying to regenerate in liver disease patients.

“That’s a problem because a person that’s been drinking and destroyed over 50% of their liver cells still has 50% of the cells functioning,” Kalsotra said. “Because the liver is injured, it asks 50% of the cells to divide, become fetal and regenerate. The pressure is on those cells, and they get stuck, but what happens is they are neither proliferative nor adult-like, so they’ve lost function.”

The team employed several research methods to explore potential causes for this phenomenon. This included replicating liver disease in mice and comparing healthy and diseased livers by sequencing the RNA and DNA from cells in the liver.

Kalsotra and his team recently received a five-year grant to look further into potential treatments for liver disease. Kalsotra said his first step is determining how to address inflammation, a prominent symptom of the illness.

“Our hope is to find what are the best targets that we can go after without inhibiting inflammation,” Kalsotra said. “Inflammation is necessary for most responses, even for normal regeneration. You cannot turn on inflammation without turning on regeneration. Inflammation is out of control and the hope is having more targeted therapy for the bad parts of inflammation.”

Inflammation isn’t the only problem Kalsotra wants to address in the next five years. Another priority is trying to reverse the misprocessed RNA in livers by packaging small RNA molecules into lipid nanoparticles.

“The platform is ready to be used, but we need to identify which RNAs we want to go after, how we make the packaging, and at what stage we release them during the disease progression,” Kalsotra said. “We also want to see if it’s reversible in animals. Hopefully, we get positive results from animals, so we could move on to humans in the future.”

Since his team’s findings were published, Kalsotra noticed the amount of support he’s been getting from experts in his field, resulting in several invites to conferences to present more of his work.