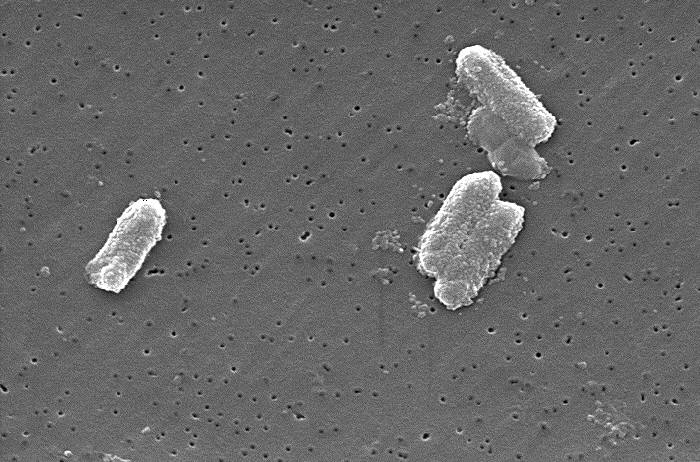

On Sept. 23, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a 70% increase in infections of the drug-resistant bacteria NDM-CRE in the U.S. between 2019 and 2023, which has few effective treatment options and high mortality rates.

This uptick represents how there are more than three cases per 100,000 people, whereas before there were two cases per 100,000 people.

Known as “nightmare bacteria,” NDM-CRE, alongside KPC and Oxa-48, is one of the main carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Carbapenems — the safest and most effective antibiotic on the market — are considered the drugs of last resort, said Brenda Wilson, professor of microbiology.

These broad-spectrum antibiotics work against whatever bacteria exist, according to Wilson. When resistance to the current drug generation pops up, companies make a new drug that has been enhanced — a process that takes time.

“By the time you get to the point where you need to resort to something else that actually works, it’s too late sometimes,” Wilson said. “That’s why the mortality rate in these cases of NDM-CREs is very high. It’s up to 50%, which is (a) 50/50 chance of living.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

NDM-CRE can cause “pneumonia, bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, and wound infections.”

There has been no evidence of an increase in local NDM-positive CRE cases, wrote Robert Davies, director of planning and research at the Champaign-Urbana Public Health District, to The Daily Illini. There has been one local case of a carbapenem-resistant organism since 2019, which was KPC-positive, reported to CUPHD.

Wilson said the CDC report told doctors to conduct a diagnostic screening as soon as they think a bacterium may have resistance. She said the strain that has caused the biggest problems in United States hospitals is KPC, also known as Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase.

Other threats to public health

The CDC is expected to release information in 2026 on at least 19 antimicrobial resistance threats. One such threat previously reported on was Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Wilson said.

Since TB has a different cell wall than other bacteria, there are about six antibiotics that can be used against it. There are some strains of mycobacteria where first-line antibiotics — the ones doctors immediately prescribe — do not work.

“These (first-line antibiotics) are the ones that are relatively cheap, that are very safe, that (are) tried and true — work almost every time,” Wilson said.

Wilson said that when these go-to drugs are not effective, doctors turn to second-line antibiotics, which are more expensive, can only be given through IV and may have side effects that make patients sick and less willing to take them.

“This is one of the reasons why, when patients have TB, the healthcare workers monitor you to make sure that you actually adhere to the regimen and take it, because the TB regimen is six to nine months,” Wilson said.

In hospitals with vulnerable populations where first-line drugs do not work, doctors test one antibiotic after another until finding one that does, according to Wilson. In the process, a patient may become gravely ill and die before the doctors find an effective antibiotic.

The problem with dormant bacteria

As patients take an antibiotic regimen, Wilson said most bacteria are wiped out over two or three days, but some go dormant.

“They get inside tissues,” Wilson said. “They get inside areas where the blood is not circulating as rapidly. Then they just hide, and they don’t grow.”

The dormant bacteria are slightly more resistant than bacteria immediately cleared away, according to Wilson. When that remaining bacteria is transmitted, the receiver needs to take an amped-up dosage of antibiotics.

Why now?

As people go more places due to travel, bacteria spread has become easier and more prevalent, causing increased awareness of the problem, Wilson said. She said many do not realize that bacteria acquired through the fecal and oral route, including contaminated water and food, cause the most problems.

“The bacteria that have these resistances go into our wastewater,” Wilson said. “Other bacteria now can get those resistances, too.”

Prevention

Wilson said she wanted to emphasize how, as individuals, we have a role to play in preventing the spread of bacteria, such as having cleaner water and reducing pollution. With less room for spreading disease, the need for antibiotics decreases, she said.

“Now the drug companies can actually have some time to make more,” Wilson said.