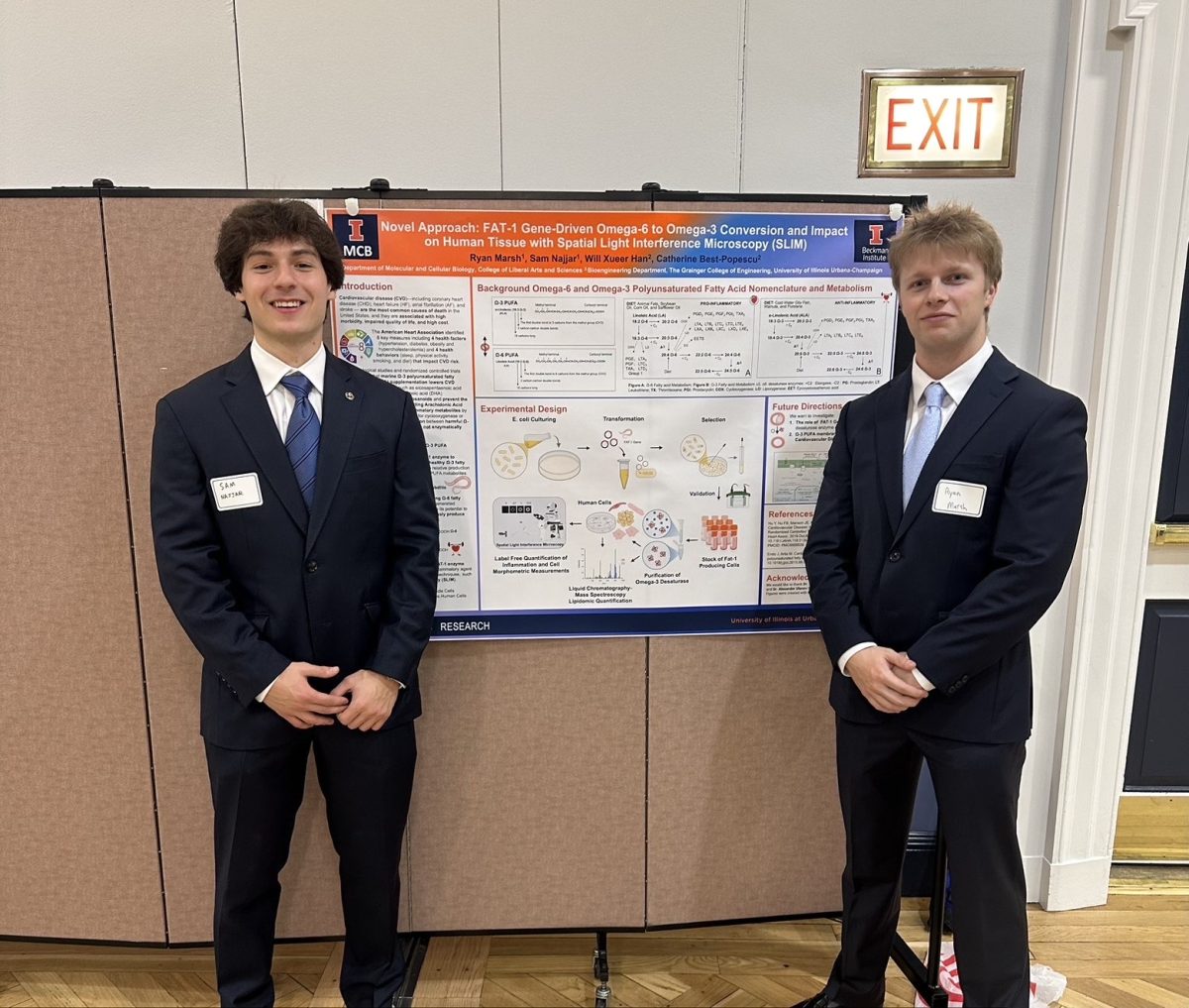

Undergraduate researchers at the University are studying an enzyme that can convert omega-6 fatty acids into omega-3 fatty acids, a conversion they say could reduce the risk for inflammation associated with cardiovascular disease.

The two researchers, Ryan Marsh and Sam Najjar, seniors in LAS, are both honors students in the School of Molecular and Cellular Biology. They work in the Cellular Neuroscience Imaging Lab, run by Catherine Best-Popescu, professor in Engineering.

Why focus on the different fatty acids

Fatty acids are the essential building blocks for fats. They have numerous biological roles, including providing energy and serving as cell membranes. Some fatty acids are essential for humans, including omega-3 fatty acids and omega-6 fatty acids.

According to Najjar, a typical Western family diet is more concentrated with omega-6 than with omega-3 fatty acids. Experts say a healthy ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids is likely between 1-to-1 and 4-to-1, but studies suggest that people who follow a typical Western diet may consume a ratio of between 15-to-1 and almost 17-to-1.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Najjar said that this ratio is bad because the high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids can result in oxidation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

LDL cholesterol impacts our body because it is responsible for transferring bad fatty acids into our tissues. When oxidized, it can contribute to inflammation and plaque buildup that could lead to a heart disease known as atherosclerosis.

Najjar and Marsh say this fatty acid imbalance is strongly correlated with cardiovascular disease. One 2024 study from the University of Georgia found that an imbalance of these two healthy fats may impact one’s risk of early death.

The students believe that an enzyme specific to the conversion between the two fatty acids can combat this risk. An enzyme is a biological catalyst that speeds up chemical reactions in biological organisms.

According to Marsh, they are working with an enzyme called a desaturase, which shifts the position of a double bond in a fatty acid. According to them, this shift is what allows omega-6 fatty acids to be converted into omega-3 fatty acids.

The students conducted experiments in bacterial cells, which they say showed a causal relationship between greater conversion to omega-3 acids and lowered risk for inflammation related to cardiovascular disease.

“Previous studies have shown this enzyme can reduce cardiovascular risk in transgenic mice,” Marsh said. “Our goal is to explore whether that same mechanism could be applied to human cells.”

In order to find more information about the enzyme, they had to locate the gene that produces it and manipulate it in order to observe their desired experimental conditions.

“The fat-1 gene encodes the exact enzyme responsible for converting omega-6 fatty acids into omega-3 fatty acids,” Najjar said. “Once we identified that gene, we knew it was what we had been searching for.”

Motivation for the Study

The researchers launched this project from scratch, saying that it resulted from their own interest. More specifically, what interested them was that they wanted to solve a biological problem.

Seeking faculty mentors, they pitched their project to professor Best-Popescu, who they said welcomed them.

“This project was built entirely from the ground up,” Najjar said. “We identified the gene through literature review, designed the experiments ourselves and carried out the lab work independently.”

Though they are happy with their progress thus far, Marsh said the production of the enzyme in the lab was difficult, but made the experience more worthwhile.

“One of our biggest challenges has been expressing the enzyme efficiently, since it’s a transmembrane protein and difficult to produce,” Marsh said. “But overcoming those challenges has been one of the most valuable learning experiences of our undergraduate careers.”

Future directions

In the near future, the student researchers plan on shifting from bacterial cell experiments to human tests to see if increased expression of the enzyme can lead to lower inflammation within human cells. If they can show said results, this can lead to a big breakthrough toward reducing heart disease.

“Next, we plan to test whether this enzyme can reduce inflammation in human cardiovascular cell lines,” Najjar said. “If successful, it could represent a major step toward translational applications.”