Surge in college student voters may impact 2020 election

Sep 30, 2019

A surge in college student voters may show an ongoing change in the political landscape on college campuses and could affect the upcoming primary elections next year.

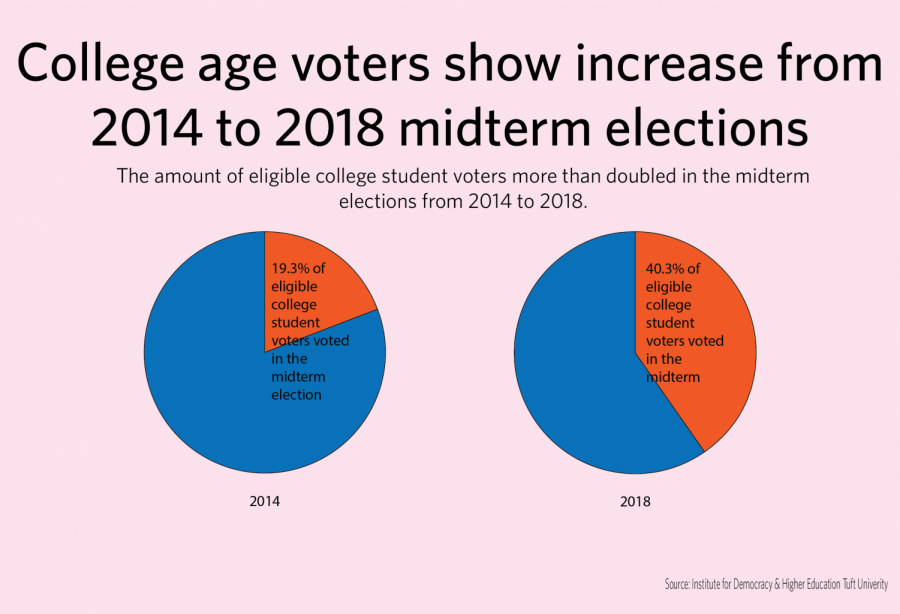

A research study recently published by Tufts University’s Institute for Democracy and Higher Education shows that college student voter turnout, from 2014 midterm elections to 2018 midterm elections, more than doubled. In 2014, 19.3% of eligible college-age voters voted, whereas 40.3% voted in 2018. The study reports an increase in all voters throughout the United States but reports a significantly greater increase in voters that are college students.

David Brinker, senior researcher at the IDHE, said he thinks it is partly due to a shift in the way college students are thinking about politics.

Brinker said he has seen a general rise in student activism on college campuses and more students are feeling they can voice their political opinions. Voicing political opinions is becoming more of an integral part of being a student and the student experience, and is now being considered a bigger part of the purpose of college, Brinker said.

Another reason, Brinker said, is that political views may be getting more personal and polarized. He said because of this, “your attachment to your political party is more directly tied to identity, and, therefore, is more of a motivation to become engaged.” Students may feel a much stronger connection to their political identity and views, and thus develop a stronger proclivity to voicing their views, through political activities like voting.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The University seems to follow this trend. Jonathan Bonaguro, senior in LAS, said he has personally experienced greater interest in politics from fellow students since his first year on campus. Bonaguro pointed directly to the election of President Donald Trump.

College-age voters grew up with Barack Obama as their president, who often did well with this group and supported their political interests, Bonaguro said. Trump does not, in general, support college-age voter’s political interests, and his election served as a wake-up call to many student voters.

This prompted some college-age voters to start voicing their political opinions and have their voices heard; voting was one of the ways for them to do this.

Both Bonaguro and Scott Althaus, professor in LAS, said they agreed that it is hard to judge how big of an impact this surge in student voters will have in the upcoming primary elections. Many voters will vote in the midterm elections and not show up to the polls two years later.

“Voting is sort of like how cigarettes used to be. It’s a hard thing to pick up, but once you pick it up, it is a hard thing to let go,” Althaus said. “The challenge is that young voters don’t yet have the habit.”

Because young voters do not have this habit, campaigns are not willing to reach out to college-age voters. Bonaguro said this makes college campuses a political “dumping ground,” a place where political campaigns test out strategies, without actually putting any real effort or money in targeting the student demographic.

If college-age voters continue to grow like they have been, then this will eventually change, and student voters will start to have a bigger political voice, Althaus said. College-age voter’s interests will be more represented in politics and will have a greater effect on future political outcomes.

“I am continually reminded in the interactions I have with undergraduate students on this campus that our future is in good hands,” Althaus said. “But we need to get those good hands into the habit of making their political views known in a way that will register as making a difference politically, and voting is absolutely one of the ways that that happens.”