Nobel Prize in Physics reminds us to focus on female scientists

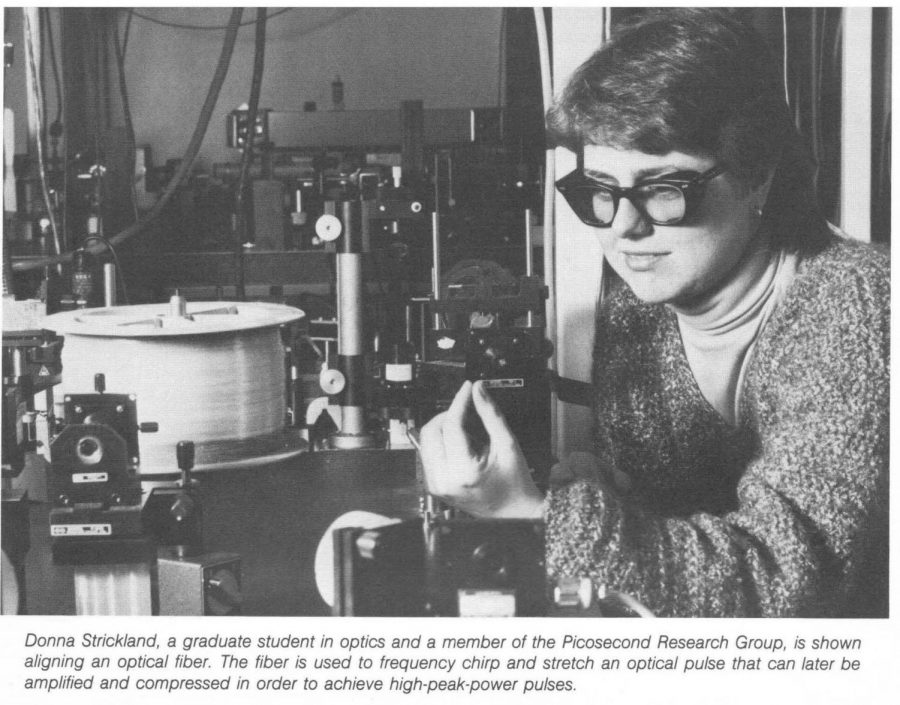

Donna Strickland on Jan. 1, 1985, aligns an optical fiber as a graduate student at the University of Rochester. Strickland was among three recipients to win the 2018 Nobel Prize and the third female scientist in history for the prize in Physics.

Oct 11, 2018

Last Tuesday, the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Arthur Ashkin from the United States, Gérard Mourou from France and Donna Strickland from Canada for groundbreaking inventions of applying laser technology to biological uses. Dr. Strickland is only the third female scientist in history who has won the Nobel Prize in physics, which is a reminder that we cannot overlook female scientists.

Female scientists receive less attention from the society than male ones. When we talk about credible female scientists, Marie Curie might dominate the conversation. And as the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in 1903 and the first person to win a second one in 1911, she deserves to be remembered by all. However, some may find it odd that we solely recognize her as a representative for female scientists since 1900. It might explain the fact that only three female scientists have won the Nobel Prize in Physics until now.

In the early 1980s, Margaret Rossiter presented two ideas for understanding the statistics behind women in science, as well as the disadvantages women faced. She coined the terms “hierarchical segregation” and “territorial segregation.” The first term describes the phenomenon in which the higher the chain of command in the field, the smaller the presence of women. The latter describes the phenomenon where women cluster in scientific disciplines. Many other sociology researchers believe contributions of women to physics are greatly diminished because of unfair payment in equal positions, and lacking the status they deserve.

Their lower salaries in the scientific community are also reflected in statistics. According to a 2018 report, provided by National Science Board, the median salaries of female scientists and engineers with doctoral degrees were 30 percent lower than that of men in 1995. As the data shows, there was less participation of women in high-rank scientific fields and positions, and female majorities in low-paid fields. However, even with men and women in the same scientific field, women are typically paid 15 to 17 percent less than men are. Even at the University, only 40 percent of faculty at the Department of Physics are female.

This needs to change.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

It is important to look at factors outside of academia occurring in women’s lives at the same time they are pursuing an education and career search. The most outstanding factor occurring at this crucial time is family formation. As women continue their academic careers, some are also stepping into new territory. Criticisms can come from marriage or even wanting to start a family.

There is an important reason: family values. When family values occupy society, there is less space for women to pursue their own academic and professional goals. Some may say women are expected to conform to traditional roles, instead of conducting research or taking full-time jobs. To assume a woman’s role as a caretaker is inherently wrong. Scientific research often diminishes when these traditional values are put in place.

The lack of female scientist organizations might be another reason. Even though we have various kinds of scientific organizations where women play an increasingly important role, there should be more exposure.

Luckily, changes are happening. A number of organizations exist to combat the stereotyping that may stray girls away from careers in physics and many other areas. In the U.K., The Women in Science and Engineering Campaign and the U.K. Resource Centre for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology are collaborating to ensure that some of the best brains in the country stay in the science fields.

In the United States, the Association for Women in Science is one of the most prominent organizations for professional women in science. In 2011, the Scientista Foundation was created to empower pre-professional college and graduate women in STEM. Some universities also have organizations aiming to inspire young female researchers, such as the Science Club for Girls.

However, issues still remain. On June 9, 2015, Nobel prize-winning biochemist Tim Hunt spoke at the World Conference of Science Journalists in Seoul. Prior to applauding the work of women scientists, he described emotional tension, saying, “You fall in love with them, they fall in love with you, and when you criticize them they cry.” His remarks were widely condemned, and he was forced to resign from his position at University College London. Unfortunately, some male scientists did not think he was incorrect.

Female scientists, and to a larger extent women in STEM, are vastly important for the betterment of humanity. They’ve endured years of mistreatment and disrespect — it’s about time for us to give them the credit they deserve.

Daniel is a graduate student in LAS.