Midterms force cramming, not learning

Oct 27, 2018

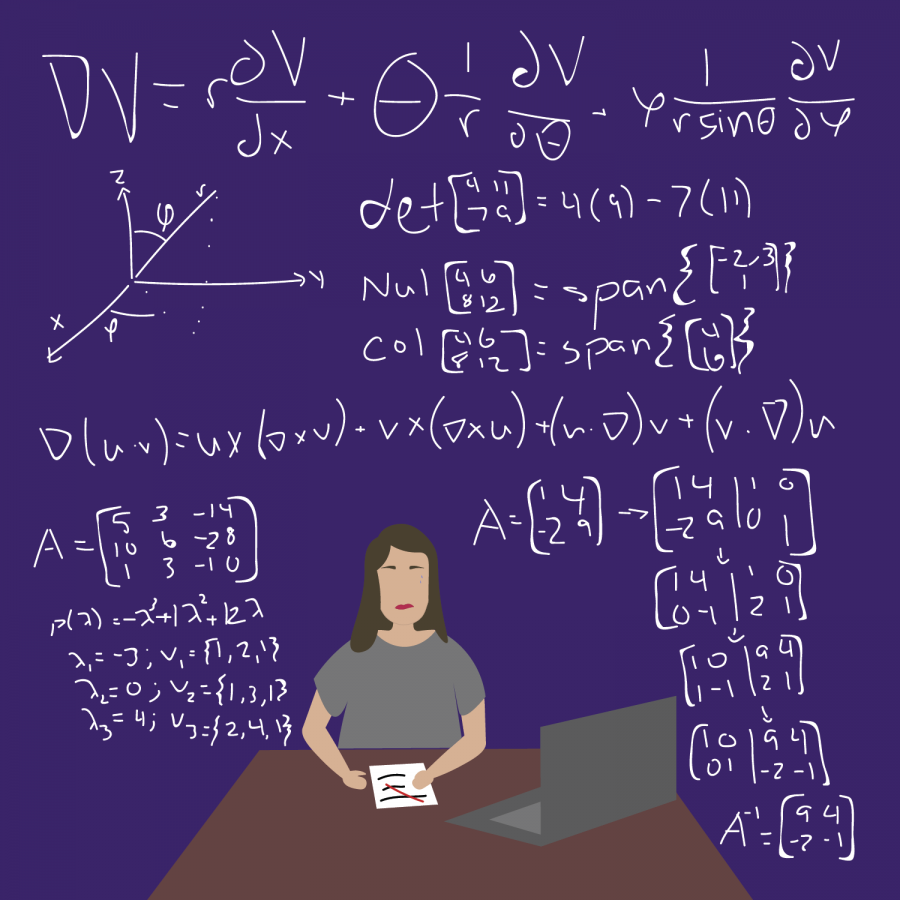

It’s midterm season. The last vestiges of summer are still hanging on, but the brutal 2 p.m. heat does nothing to ease the icy chill of the blasting air conditioning inside giant lecture halls at half-capacity. The interminable symphony of rickety desks and creaky chairs is interspersed only by a chorus of coughs and sniffles because, of course, it’s also flu season.

In the golden days at the beginning of the semester, my professors had the audacity to look me in the eye and tell me they honestly didn’t believe in grades. Exams, they declared, were a terrible measure of a student’s true ability and had an extremely negative impact on learning. Of course, exams were unfortunately 80 percent of the grade in the course, just to be fair to all students.

As a sophomore, there are a couple of 400-level courses in my schedule that are run almost entirely at the whim of the professor. Instead of the rigid, standardized format of courses with a 20-year history and at least as many practice exams, the professors’ only advice for midterms is to practice all content covered in lecture and to make sure that we’ve “mastered the material.” This isn’t an entirely unreasonable expectation, but it’s definitely not a small task to master six weeks worth of highly complex material.

If every one of my five classes asked me to master all the content in every lecture since the beginning of the semester and review every homework problem and review material not covered in class to even have a chance of doing well on the midterm, I’d be dead. Except the more high-level classes I take, the more likely it is I’ll end up in those dire situations.

There is, of course, the argument that it’s up to the student to be prepared for whatever a class throws at them. If it’s too hard, take a lighter course load or just accept they’re going to take the “L” without complaint. Just work harder, do better or resign to accepting less.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

And for now, yeah, that’s the only solution. But we shouldn’t be content with the way things are. I’m constantly cramming, constantly stressed. I’m not a genius. I can’t master difficult material without a significant amount of time to consider it, and I make dumb mistakes doing simple calculations. I usually don’t have the time to actually understand material before I’m tested on it, and I end up memorizing situations and steps instead of the theories behind them, which it makes it almost impossible to retain that knowledge for the future.

Those flaws don’t reflect worth or capability of success in a technical field; they’re just a fact of life because we’re all human beings with limitations.

There’s a disconnect between what I want out of my education and what I’m actually getting. I want to be able to understand everything I’m learning. I’m in my major because I want money, but also because I have a genuine interest in what I’m studying. I want to be able to spend enough time on my classes to really get something out of them, but if I take a course load light enough to allow that, I’m not going to graduate in four years.

It’s easy for me to sit here and complain that we need a universal, systemic change in the way we educate and in what we should expect from an education. A solution is near impossible to even contemplate given the scale and complexity of the problem we’re considering. It’s equally as incomprehensible that we should remain satisfied with the status quo or just accept the state of matters as is. We’re paying for our education in time, in money, in sanity and confidence and health.

We’re betting our futures on it. It’d better be worth it.

Sandhya is a sophomore in LAS.

[email protected]