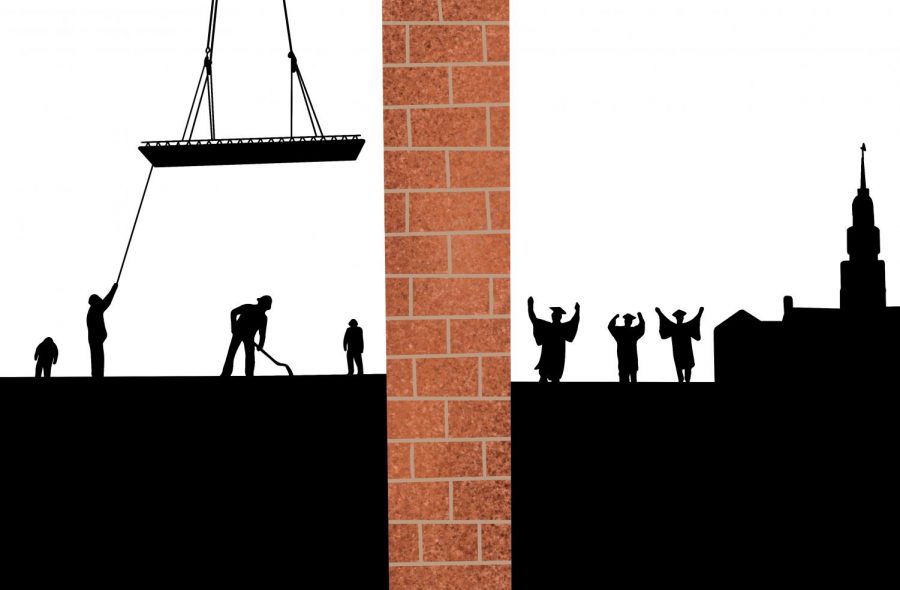

Opinion | College heightens class division

Apr 19, 2020

College is viewed as a quintessential part of life in America, a phase of relatively low responsibility compared to “true” adult life and more freedom than high school. Young adults are leaving home for the first time, but are still students. Because of this, it is sometimes referred to as “extended adolescence,” alluding to its role as a period of learning and development that, in previous generations, may have been the beginning of “real” life.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, college enrollment in America mostly swelled to its current levels following World War II, particularly during the 1960s–70s. In the 1959 school year, roughly 3.6 million students were enrolled in some form of college. By 1979, over 11 million were enrolled. Since then, college has been increasingly viewed as the biggest step towards a “better life,” if such a thing can be so easily measured. College is ostensibly an opportunity to further specialize and hone a skill set for the workforce, but in reality, it often exacerbates class division and functions as a means to make money off of impressionable high school graduates.

For years, college has been marketed to young people, which has engendered a significant student loan crisis. The average amount a college graduate pays on student loans has increased by over $100 per month since 2005. When college is encouraged to everyone, people will attend even if it is not in their best interest, especially if someone else will earn another kind of interest.

But what is most important is this: college is not for everyone. College should be an option for those who want it, but young people need to be given a better understanding of what options are available after high school. Many jobs do not require 4-year degrees, and many others require trade school or other forms of post-secondary education. College should not be treated as the “one size fits all” path for high school graduates.

This phenomenon not only causes naive high school graduates to accrue massive debt in a short amount of time but also worsens the quality of education available to each individual student. This does an injustice to everyone involved (other than student loan lenders) and orients future generations and by extension, the country, for failure. The goal of universities should be to provide the best education possible to students in order to brighten their future and the future of society as a whole.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The opportunity to attend college should not be taken for granted, nor should it be taken lightly. The ability to attend college, particularly a more expensive and selective state or private institution, is a privilege. Many people, even very smart and capable students with scholarships, cannot afford college and don’t want to incur the massive debt associated with student loans and decide to forgo the process altogether. This is the fundamental flaw of the university system in America.

When college becomes a means to generate capital, and the value of education is given secondary consideration, people have been effectively tricked. Not only are people not going to college for the right reasons, but the wrong people in the first place are going. This is reflected in the fact that the national college graduation rate is declining.

Unfortunately, college is frequently associated with intelligence, and people who cannot or choose not to attend are looked down upon. But for many, the choice not to go to college is more economical. There are many reasons that one wouldn’t want to go to college, and the decision of whether or not to go should be weighed heavily.

Sadly, many jobs use college as an arbitrary “barrier to entry”. There are many professions that need a degree, but far from all of them. Often, the degree acts as a de facto way to perpetuate the class divide. People who can afford to go to college can get good jobs and afford to send their kids to college: the cycle repeats itself.

Part of this is the frequent branding of college as “the best time of your life,” with the bleak implication that there’s nowhere to go but down after the age of 22, less than a third of the average American’s life expectancy. If one accepts this premise as true, why live for another four to five decades after graduation? I can only hope in the twilight of my junior year that this is not the case.

College is a great opportunity for many people. It can be a chance at a better life for a person, especially first-generation college students. But it should be that way because of the education and opportunities it provides, not simply because a degree is a piece of paper that somehow justifies spending four years and thousands of dollars.

Dylan is a junior in the College of Media.