Opinion | It’s time for an update to the Constitution

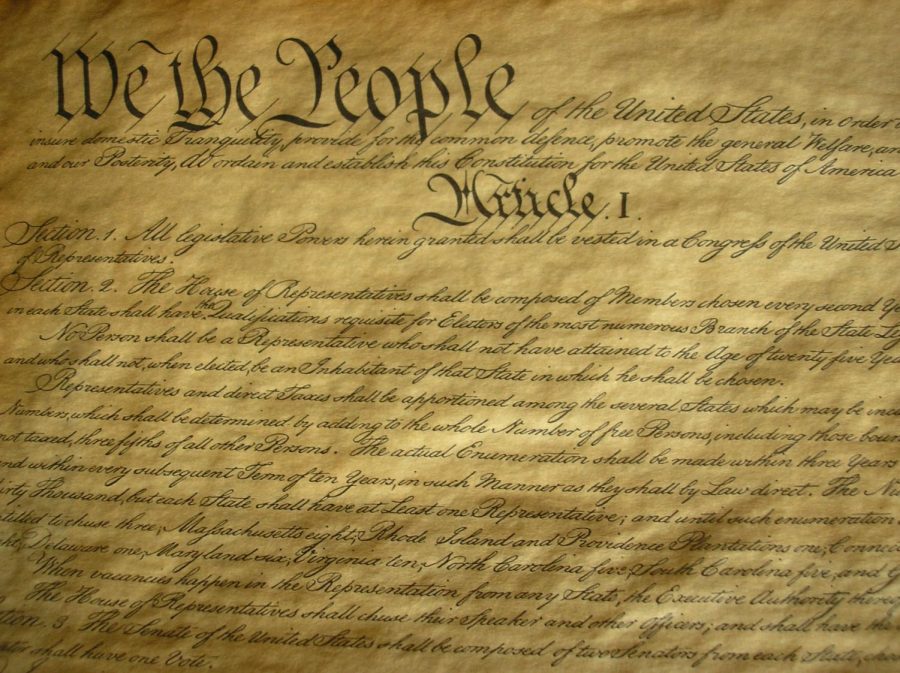

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Thorne/Flickr

The U.S. Constitution contains the 14th Amendment, which guarantees birthright citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.”

Jul 31, 2022

In the musical “Hamilton,” Founding Father Thomas Jefferson gets a sarcastic musical number while arriving back in America after having missed the bitter battles over constitutional text. Jefferson was in France during the Constitutional Convention.

But perhaps if Jefferson were present for the Convention, he would have argued for a “refresh” of the document every 19 years, just as he once did in a letter. The idea stemmed from the basic truth that societies develop as new generations usher in new ideas and champion new causes.

There is only one constitution older than the United States Constitution — it belongs to the mountainous microstate of San Marino.

Most governments have newer, more modern constitutions. Chile is currently drafting a new constitution that is seen as incredibly progressive. According to the University of Chicago Law School, the average lifespan of a constitution is a measly 17 years.

But the lifespan of America’s Constitution is not necessarily a testament to its strength and efficacy. After a regressive and reactionary Supreme Court term, a truth that has been plain for decades has now become unavoidable: America would greatly benefit from a constitutional refresh.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The Constitution, in its inception, represented the new, fresh democratic ideals that galvanized the masses at the end of the Age of Monarchy. It progressively established limits on power, sought to prevent tyranny and enumerated essential freedoms. But in the 21st century, it is clear that it does not meet the demands of modern democracy and in some ways serves as a hindrance.

The American Constitution should be jealous of some of the amendments produced by other contemporary, new constitutions. To date, the Constitution lacks an Equal Rights Amendment, an explicit right to privacy, badly-needed electoral reforms, an environmental protection clause and a limitation of executive powers through a clear definition of “war.”

After the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Democrats must push for an unambiguous, constitutional right to privacy to avoid “textualists” interpreting the document only as it was meant, in an era before the White House even had modern plumbing.

The ERA is long overdue for ratification, which nearly succeeded in the late 1970s. Some believe an ERA would be redundant, but the Roberts Court has proven the United States is capable of backsliding. Today, an ERA could go further than gender equality and protect all types of marginalized classes.

Modern constitutions have addressed modern problems, such as climate change and environmental degradation. An ecological protection amendment would be progressive and welcome, especially in the wake of the Court’s defanging of the Environmental Protection Agency.

The United States has embraced the reality of “constitutional crisis,” mostly due to an electoral system that has, with some help, warped itself so drastically that it seldom produces outcomes that reflect the people’s will.

This hypothetical 21st-century constitution would ideally clarify new rules for the electoral process. It would codify the ideals of the ever-debilitating Voting Rights Act of 1965, outlaw partisan gerrymandering, reject the Electoral College and, in a perfect world, embrace a unified, effective ballot system like ranked-choice voting.

This wishlist of proposed amendments would only be deemed likely by someone with their head in the clouds. Still, without some of these aforementioned changes, the United States will only grow as much as a document from 1789 would realistically allow — which is to say, not much.

But this only scratches the surface of changes that should be etched into the country’s doctrine. Others have proposed amendments that codify a right to unionize or establish regulations on campaign finance. Explicit rights are undoubtedly better than the state attempting to stretch the Commerce Clause to get gun control.

A constitutional refresh would allow clarity on the contentious, antiquated language. It now requires subjective interpretations of the intentions of individuals who have been dead for centuries.

In the Bill of Rights, constitutional analysts cannot even move past the First Amendment before disagreeing on the extent and meaning of certain enumerated rights. Is the Establishment Clause meant to provide freedom to practice religion or freedom from religious coercion?

The Constitution was meant to be difficult to amend to ensure that the incremental progress that occurred was rightly organized.

However, its impossible amendment process today causes problems. It means that certain rights are held at the whims of politicians and motivated judges. It means that the country cannot address urgent matters like climate change. The failure to enshrine these rights does not mean “nothing happens,” it means that the benefit of the doubt is granted to the powerful and the privileged.

These ideas aren’t a hate poem toward the Constitution. But idolatry of the Constitution is blinding. The country needs dedicated public servants, lawyers and legal scholars who realize that the Constitution is a fallible founding doctrine. It was written during a time when slavery was widespread and few had the right to vote — how on Earth can we call that time perfect?

Conservatives love to say “the Founding Fathers would be horrified to see what the federal government has become.” The truth is, the Founding Fathers would probably be horrified to see what the constitution has become — frequent grounds for denial of progress.

In its heyday, the American Constitution was a glorious, progressive document. Doesn’t the country owe it to the authors to maintain that glory rather than trample it?

Andrew is a senior in LAS.