Growing up as a Korean American girl in a predominantly white suburb of Chicago, I had a very specific idea of what beauty was. It only took me until the age of about eight to realize that I was not it.

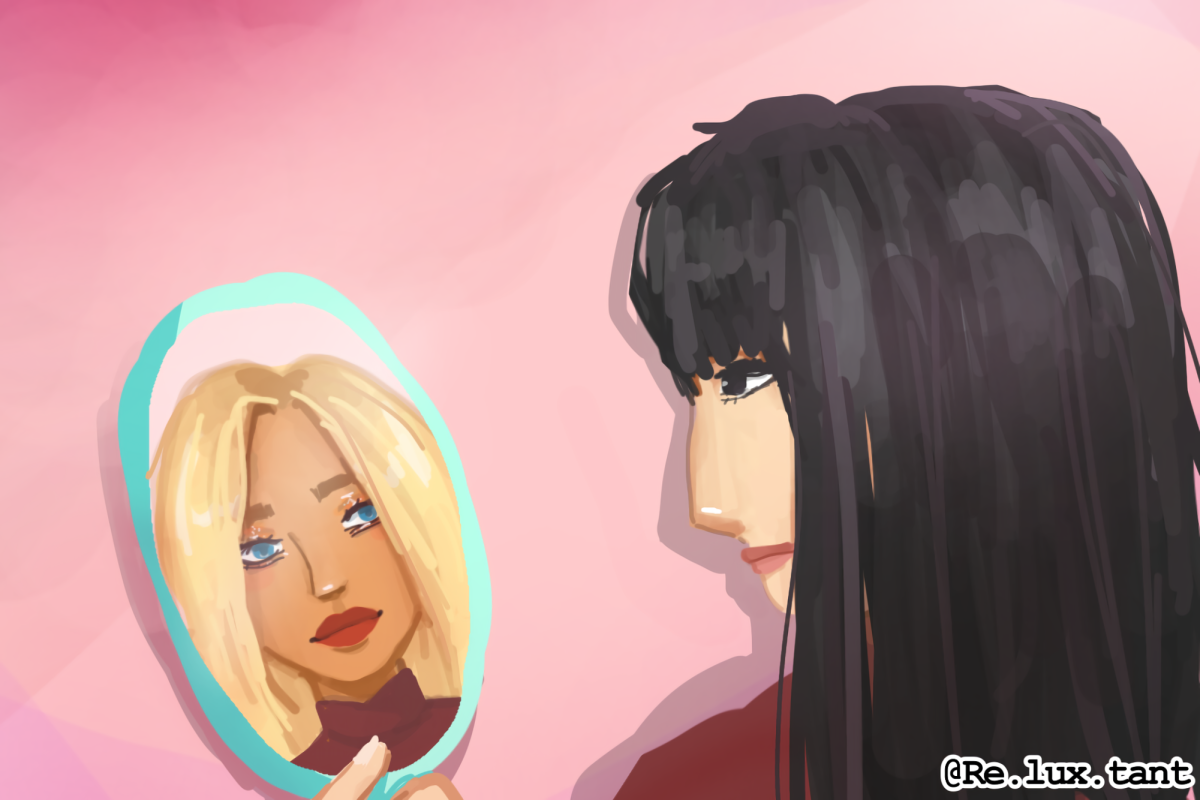

As a child, I would draw myself with blond hair and blue eyes, coloring away any aspects of my appearance that worsened my internalized racism. It never occurred to me, sitting there at the kitchen table with a pack of crayons, that maybe I wasn’t the problem.

Despite recent trends of inclusivity in the mainstream media, there is still an undeniable foundation of racism that most of society’s beauty standards are based on.

We see it everywhere: The sharp cheekbones, imperceptible body hair, pale skin and perfectly pointed nose are all tell-tale signs of a true all-American beauty. These are the features that teens are taught to envy and to strive toward, despite the fact that most are impossible to achieve for people of color — and this very well might be on purpose.

During colonialism in the early 1900s, race theorists sought to prove that white people were superior to other races in all aspects, including in physical beauty. The only way to ensure ultimate power was to deem other races as unwanted, less than or savage.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

By creating a system where whiteness and Eurocentric features were the definition of desirable, these race theorists successfully started a ripple effect that would define beauty for over a century.

The bottom line: Beauty standards have always been political.

Furthermore, these standards, in spite of their origins, continue to be a prominent part of our culture today.

One Stanford study done in 2018 found that one in five South Korean women had cosmetic surgeries done, one of the most popular being for “ssangkkopool,” or double eyelids.

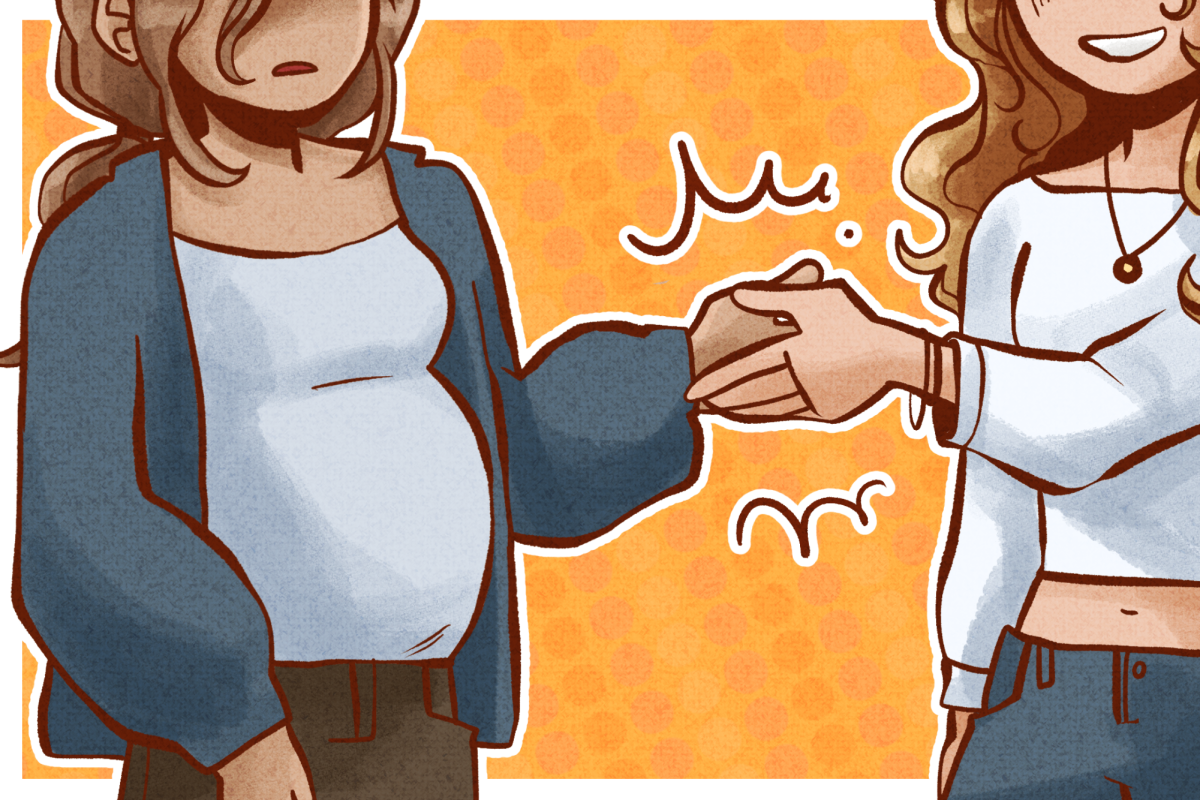

I strongly believe that one should never be shamed for getting plastic surgery and that individuals have every right to exercise control over their own bodies. That being said, I do think that a certain moral line is crossed when industries directly target young women — especially women of minority cultures — with specific ethnic features.

An analysis led by the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health reported that pressure to conform to beauty standards was the leading motivation behind the use of chemical straighteners and skin lighteners for women of color.

Reports such as these suggest that people conform to beauty standards not because of their own preferences, but because they feel a need to mask insecurities imposed by racialized beauty.

On the rare occasion that non-Eurocentric physical features are idolized, they are almost always portrayed on white women rather than on those who are part of the culture they are being taken from.

The presence of cultural appropriation in the beauty industry has become more evident over the years, but people are also waking up to how problematic it is.

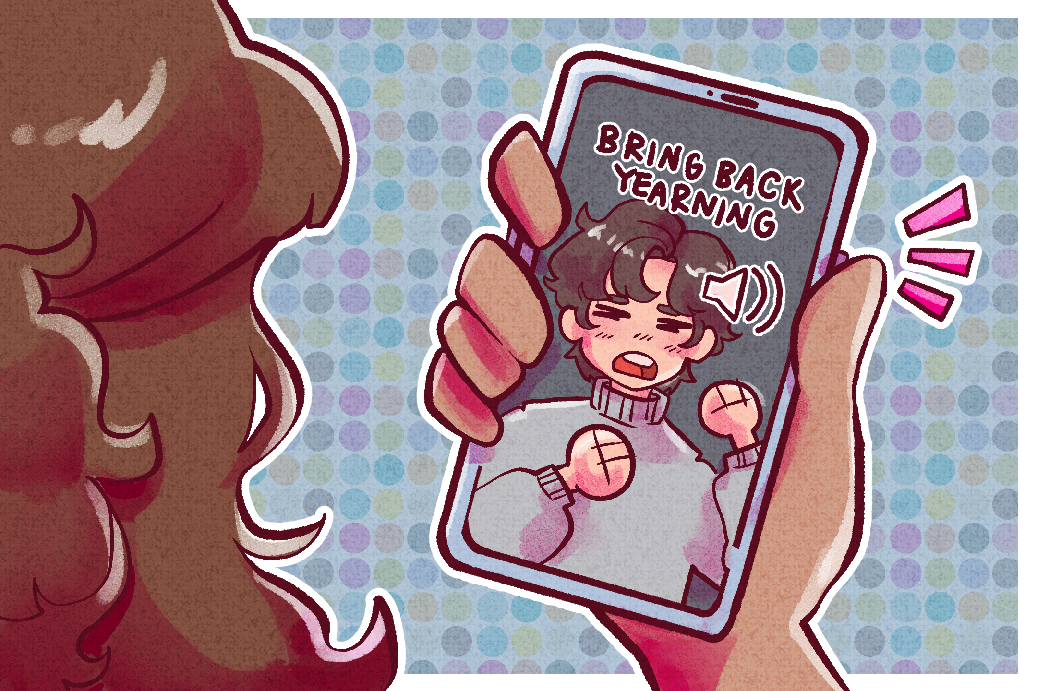

One example of this can be seen in the fox-eye trend that was popularized on TikTok in 2020. The trend consists of doing your eye makeup in an intense wing, like the eye of a fox, and then pulling back your eyes to pose — a pose that many Asian Americans remember being used to bully them as kids.

In my eyes, the issue with cultural appropriation lies more in ignorance than it does in the actual trends that white people “borrow.” It can be frustrating to see something you have been made to feel insecure about your entire life romanticized and praised because a white person is now doing it. The line between appreciation and appropriation is thin, and too many have become comfortable with crossing it.

The answer to ridding society of heavily racialized beauty standards is not to turn ethnicity into a trend, but to recognize the beauty that different backgrounds bring from all angles.

We need to dismantle the preconceived idea of beauty that has existed in our minds for so long.

My hope is that the eight-year-olds of the next generation will be able to look at their reflections without flinching and are able to see themselves as beautiful. I hope that when they draw self-portraits, they reach for a crayon that matches their true colors.

Hailey is a sophomore in Business.