This past winter break, I returned home to family traditions that carry more weight with every year that goes by. Over bowls of tteok mandu guk and galbi-jjim to ring in the new year, my mind was transported to my grandma’s old condo. Her kitchen table was crowded with hundreds of dumplings that my brother and I folded — a practice so tedious that it could only be seen as exhilarating by kids who had not reached 10 years old.

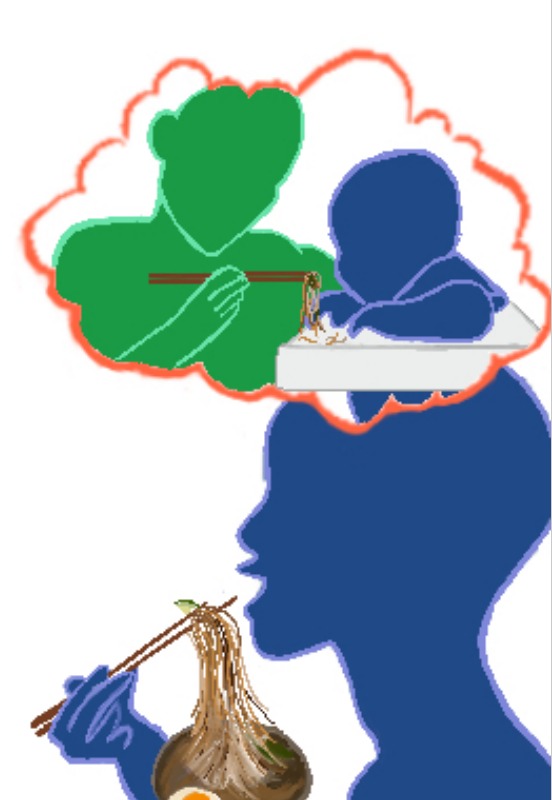

Perhaps this extreme nostalgia is the result of an increased anxiety and resistance toward growing up, or maybe it’s due to the prolonged time spent away from the environments I grew up in. Either way, I have found one thing to be true during each visit home: Food carries the most vivid memories.

Evidently, I am not the only one to have experienced this. In a BBC article, a journalist described the role food played in her turbulent childhood after her family fled from the USSR. Features correspondent Susanna Zaraysky recalled first experiencing this “gastronomic déjà vu” when she tasted wild berries she had not had since she was a toddler.

When interviewed about this encounter by Zaraysky, Susan Krauss Whitbourne, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, explained that food memories often extend past one’s conscious awareness.

“This is why you can have strong emotional reactions when you eat a food that arouses those deep unconscious memories,” Whitbourne said. “The memory goes beyond the food itself to the associations you have to that long-ago memory, whether with a place or a person.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

This instinctual response to taste reminds us of past experiences that we likely couldn’t have recalled on our own.

Boston University published a similar article citing the “Proustian Effect,” a phenomenon where involuntary memories triggered by taste or smell can help spark past social experiences or relationships. This response is often utilized in nursing homes to promote sense memories and increase self-esteem.

By manipulating taste nostalgia, individuals with dementia or aging minds can reach pieces of their lives that they have not seen in years. Some might suggest that the effect of these reactions is simply superficial — a temporary spark of joy and nothing more.

On the contrary, I would argue that a moment of happiness is often all you need.

When I look at my grandpa — a long-time Alzheimer’s patient who assumes that I am family but can’t quite remember my name — I see the irreplaceable value that memories truly carry. Subsequently, I see the fatigue in my grandma’s eyes on the bad days when he refuses to eat full meals or leave his bed.

More often than not, these are the days that we see the most; but they’re not the ones that make the greatest impact on me.

The days that burrow themselves into my long-term memory are the ones that start with that small spark of joy. They are the ones where my family breathes a collective sigh of relief as my grandpa fully cleans a bowl of mul-naengmyeon — a North Korean soup with cold buckwheat noodles. It is a dish that somehow reaches through gray matter and reminds him of the young boy he once was and the home he once had.

For one day in the summer, my grandpa is like how he was before his sense of self escaped him. He eats, he laughs and he makes the same joke about how I shouldn’t grow taller than him at least 20 times — but on this day, no one really minds all that much.

It is a moment where time stands still and, for a single meal, we live happily in the past.

Hailey is a sophomore in Business.