I recall when I was at my grandma’s house with my Aunt Bib, God rest her soul. Aunt Bib randomly said to me, “Jasmine, I need you to know that you are a Black girl.” In my head, I thought, isn’t that obvious?

Until that point, I had never questioned my Blackness before. I grew up with my Black side of the family, and it remains that way to this day. Most of the time, I’d forget that I had a whole other side of the family that was white, but even then, it didn’t matter to me. Because when I looked in the mirror, all I saw was my mother’s face.

I grew up sitting in between my cousin’s legs, tense and in pain, as she tightly braided the hairs on my tender head. I’ll always remember the smell of Blue Magic and the sound of hair beads and barrettes clinking together as they hugged my ponytails. When I got slick with my grandma, she always told me that a hard head makes a soft behind. To this day, I still have spaghetti-stained plastic bowls in my kitchen cabinets.

However, my grandma disputed her by saying that I wasn’t Black, but that I was biracial. They then went back and forth on what my identity is or should be. Aunt Bib was so passionate about fully convincing me that I was indeed Black, but my grandma made it sound like being biracial was something clear-cut.

The truth is, neither of them are wrong. Yes, I am biracial, but I identify as African American.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

First, I believe it is crucial to begin by explaining the importance and legitimacy of self-identity, and the privilege I have to be able to ultimately decide between either identity.

Racial identity is complex and multifaceted, and biracial individuals have the right to self-identify based on their own experiences and personal understanding of their racial culture and heritage. My family upbringing, cultural connections, shared experiences of racism and the strong sense of belonging within Black spaces have allowed me to be unapologetically Black.

I have the agency to define my own identity in a way that feels authentic and affirming to me. Regardless, unlike ancestry, race is a socially constructed concept. It is completely manmade; therefore, there is no “correct” way for me to identify myself. Race is less about biology and more about an individual’s own, and others’, perception.

But I was recently sent into an identity crisis. I’m now questioning whether or not I’ve been a liar by telling people I’m Black my entire life. I’m questioning if I actually fit within the Black community. Am I really not Black enough?

But I decided to call my Aunt Nicky to talk about this. She reminded me of a few things.

“First of all, your nose is a dead giveaway; it’s your mother’s. And yes, you have white in you, but you have been raised by a strong Black woman. The Black side is the side of Jasmine that represents comfort and belonging. You don’t have to pick a side, but you have the right to do so, and nobody gets to choose that for you.”

Aunt Nicky has two Black parents, but she still has people questioning her racial identity. She’s been teased for her “Eurocentric” features all her life. They’d ask, “How can you be Black? You have green eyes, freckles and you are as white as you are.” She’s literally had to argue with people over her Blackness.

Once you consider my aunt with two Black parents is light-skin, and myself with one Black parent, our shared experiences prove that race is arbitrary.

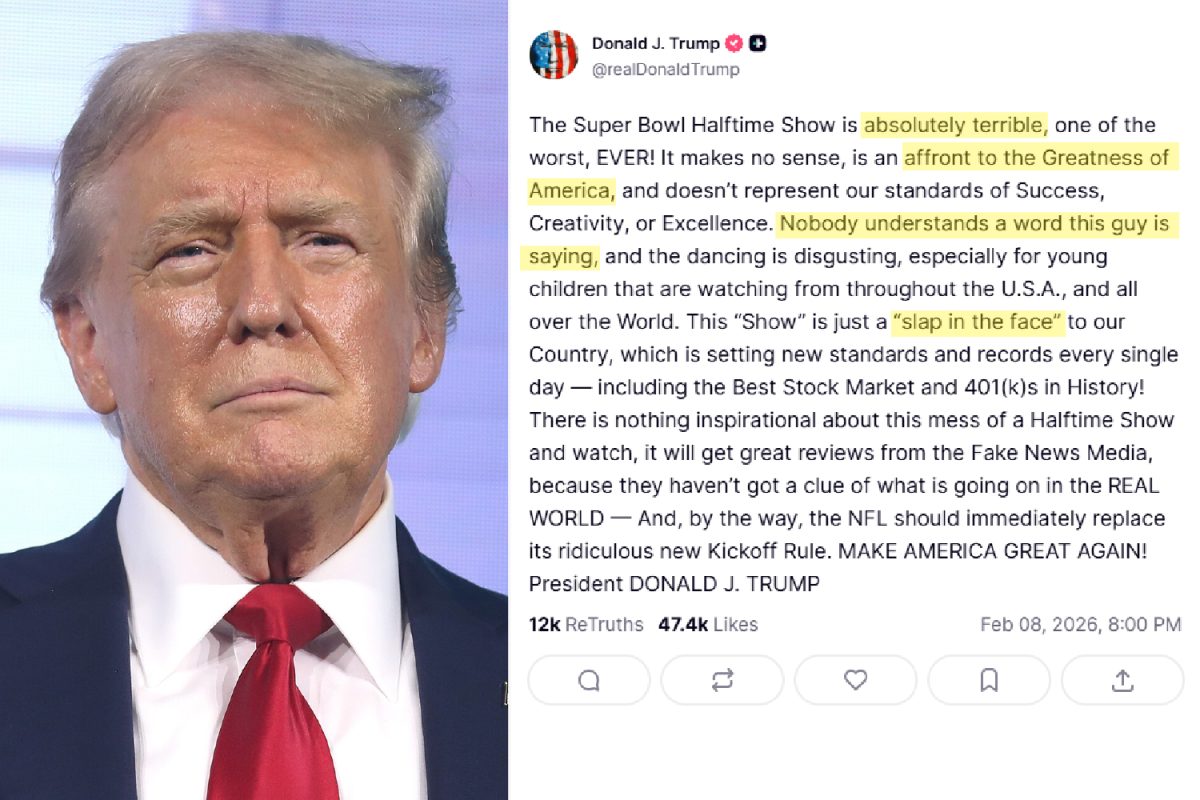

Society tells us what we are as though it’s such a fact. In reality, everyone is confused and comes up with different answers for each light-skinned or biracial person they see.

Opinions on how biracial people should identify have changed over time. Biracial children once symbolized enslaved women’s struggles with sexual abuse. Originating during slavery and persisting into the 20th century, according to the “one-drop” rule, anyone with a single “drop” of African blood in them was considered Black.

This rule has been discredited and legally abolished, but it goes to show that, again, race is completely arbitrary. Racial categories are not based on biological or genetic differences but on white America’s maintenance of power and systems of oppression.

Despite this, it’s critical for me to acknowledge the privilege I have to be able to choose. There are obstacles faced by being half-Black, but there are also privileges that come with being half-white. I have not experienced the same degree of racism that people with two Black parents or darker skin have.

Regardless, the racial policing of any biracial individual’s identity is wrong.

Racial categories are not based on biological or genetic differences, but instead on white America maintaining power and systems of oppression. Many people don’t want to openly admit to their Blackness, but in a white supremacist society, loving your Blackness is a form of political resistance. Blackness is deemed threatening or dangerous, suspect or criminal — but I will choose my Blackness every time.

That’s because being Black is something to be proud of despite the hardships that come with it. As a society, we need to realize that racial identity for biracials is deeply personal and can encompass a range of factors beyond ancestry, including cultural upbringing and lived experiences.

Jasmine is a freshman in Media.