The Trail of Tears.

Something every high school student taking AP United States History should know. Check out that singular flashcard on Quizlet, and done — one more point towards an A.

Something is deeply askew if the whole of the Native American experience is folded neatly into this clean package of suffering and strife — one of the lowest points in Native history becoming its single horrifically defining moment for the sake of brevity.

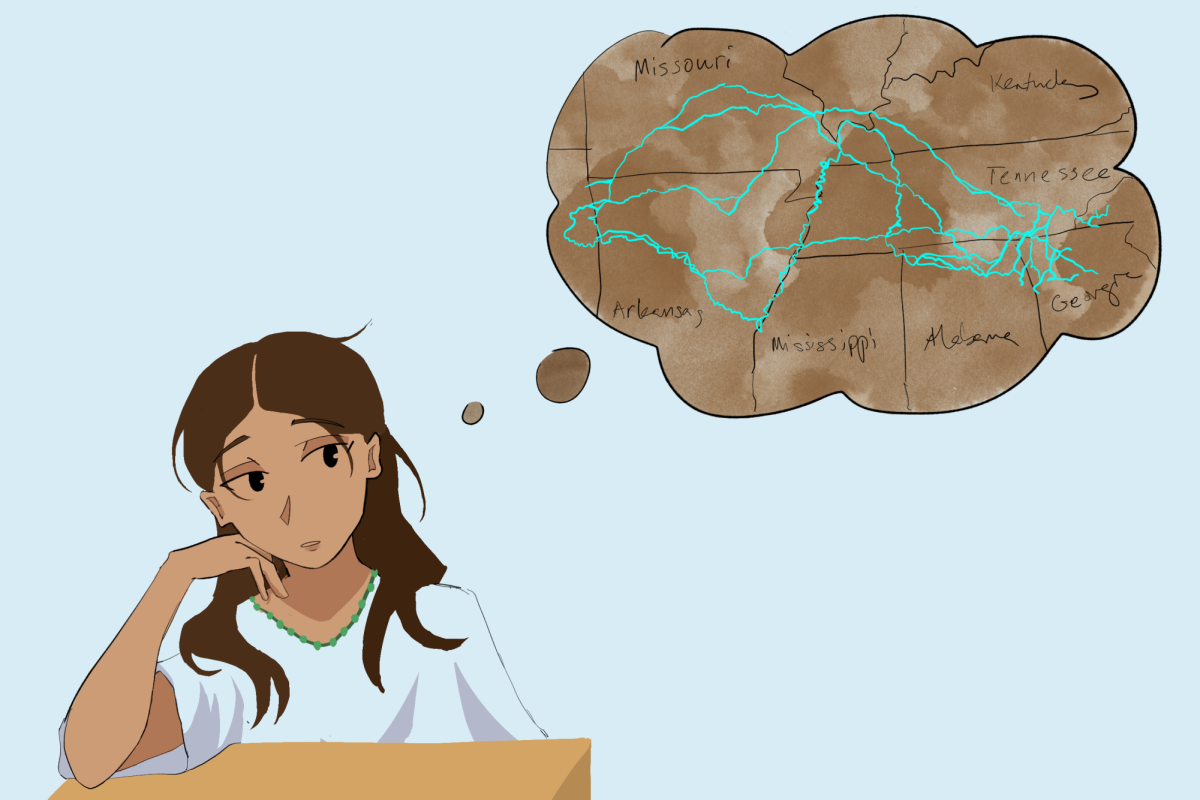

Beyond the Trail of Tears, the route of massive relocations from the 1830s to the 1850s of over 50,000 Native Americans from their homes east of the Mississippi to reserves out West, generalizations are awaiting those taught the history of the ones who settled on this continent first.

The first Thanksgiving story is the Seven Years’ War and the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

These are important events, but their typical narratives leave out one crucial element that is so often missing from Native American education — the indigenous peoples’ autonomy. In all of the commonly-taught historical events involving the natives, things simply happen to them.

What makes this so easy to fall into is that the long receipt of injustices dealt to the Native American population reaches the floor. However, if the U.S. wants to truly heal old wounds and repay the original owners of its land, it should start by integrating the proper history of Native Americans into its educational system.

It is no simple task. There is no one Native American history.

As of January 2024, there are 574 federally recognized indigenous tribes existing within the U.S., spanning across the nation with a major concentration in the Southwest. Each of these tribes has its own distinct culture and traditions, making the task of roping all indigenous history under one umbrella not only a disingenuous proposition but simply an incorrect one.

We can start by approaching the matter from a social perspective. The general population of the U.S. is aware that Native populations have suffered in the past, but present problems seem to fade into the hopeful muddled distance we have from the 1800s. An indigenous advocate group’s 2018 study found that only a third of Americans believe that Native Americans currently face discrimination.

It is from a place of ignorance, not malice, that most Americans disregard the current plights of Native Americans, including the highest rates of suicide and alcohol-related orders of any minority group in the U.S.

This can be remedied through better education, and efforts are already on the way.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian has been innovating with its lesson plans and expanding its exhibits to provide a deeper understanding of indigenous history. Not only does the museum intend to give more insightful looks into how political treaties between Native populations and the federal government failed, but it also intends to provide a voice for indigenous perspectives.

One exhibit that focuses on the Trail of Tears features interviews from descendants of the Cherokee peoples who were forced out of their lands. Their stories are not ones of passive relocation and tragedy but ones of active resistance against Andrew Jackson’s administration. The interviews also spotlight the ramifications of the removals that are still felt in Native communities today — the effects of uprooting entire nations.

Illinois is among the states making new efforts to fix the wide blindspot Native history inhabits in the American psyche.

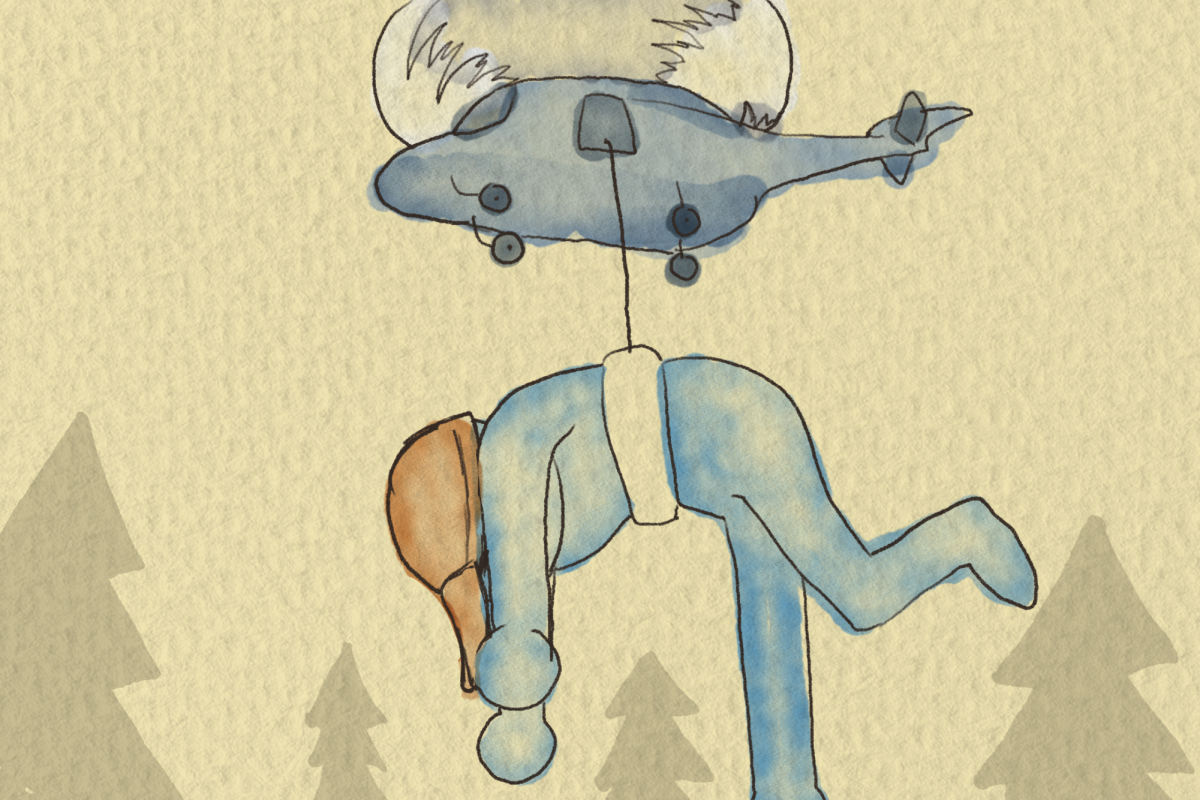

In Summer 2023, Governor Pritzker signed a bill into law that allowed public school students to celebrate their ethnic backgrounds during graduation ceremonies. The move followed a Chicago Native American student forced to sit in the bleachers at his graduation after expressing a desire to wear an eagle feather and beads with his gown.

The University of Illinois’ Department of History and College of Education have also worked to expand student awareness of Native issues, noting that the Trail of Tears is the single drop in the bucket of Native history taught widely.

However, as a university that actively reminds its student populace of its deep sorrow for being built on Native land at every possible opportunity, like a child who knocked over their mother’s vase, the University is likely not the school in most need of this outward awareness. These frequent acknowledgments from the University are nonetheless important but do absolutely nothing to give actual Natives an autonomous image in their own history.

Native American history is more than the tragedies dealt to indigenous populations. There is a mind-numbing treasure trove of vibrant culture and wisdom to be found within the communities of the original inhabitants of these lands.

The indigenous peoples of the Americas were writing their own stories long before their colonizers finally felt the guilty compulsion to do it for them. We now must let them be heard.

Aaron is a sophomore in Media.