I am going to mistype a word: opinion. Opinion. Opinion. Wait — every time I typed that word, Google Docs automatically corrected my spelling.

I tried to make a mistake, and yet it was mechanically overridden to say the same thing over and over again. Even while typing that last sentence, a ghostly light-gray font appeared following “overr” to help me complete writing “overridden.”

In other words, a platform I use for academic and personal purposes forced artificial intelligence assistance onto my writing.

The New York Times reporters Neil Vigdor and Hannah Ziegler published an article on Oct. 29 about a scandal at our University. Wade Fagen-Ulmschneider, professor in Engineering, and Karle Flanagan, professor in LAS, found that students in STAT 107: Data Science Discovery had been cheating on attendance, somehow completing the daily attendance form despite not being in the lecture hall.

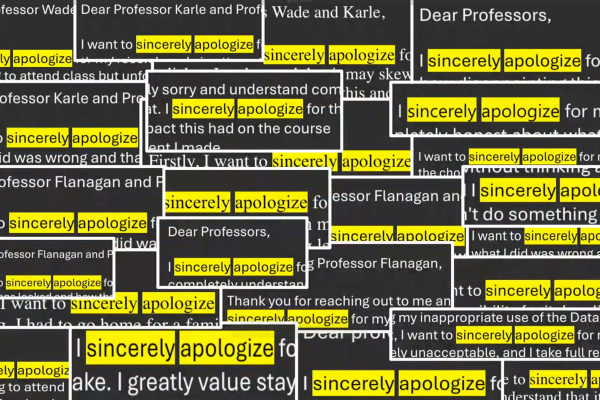

After confronting their students, Fagen-Ulmschneider and Flanagan — known as Wade and Karle to students — received an influx of apology emails. But then, they started to notice a pattern. Dozens and dozens of the emails started with “I sincerely apologize.” The professors claim the students used AI to generate the apology emails in response to the accusations of academic dishonesty.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Vigdor and Ziegler effectively describe this situation, providing information on the University and the course’s AI policies as well as perspectives from the professors, students and Allison Copenbarger Vance, deputy associate chancellor for strategic communications and marketing.

But this is as far as they go.

The professors’ accounts do not provide any proof that the students used AI to generate their emails, despite the fact that part of the headline of the article is “(Students) Used A.I. to Apologize.” The cover photo is a trending collection with “sincerely apologize” highlighted in yellow among a sea of responses that, despite being cropped, clearly show different phrasing and writing voices.

Some students address them as “Professors,” some by their last names, some by their first names. Some students start with “sorry,” while others thank them for reaching out.

But then again, it’s hard to tell exactly what each student said differently; this cropped picture of two dozen emails is all we get.

Despite the “Data Science Duo” claiming they received “more than 100” nearly identical emails, there is a deliberate telescoping of student responses. The New York Times’ article focuses on a minute detail of the students’ apologies, ignoring that the emails all sounded different outside of the one phrase.

Why did so many students coincidentally say “sincerely apologize,” though?

Vigdor, Ziegler and the professors’ arguments all fail to acknowledge the glaring truth: The students of STAT 107 have been trained by society and the University curriculum to sound the same and to (sometimes) use AI in writing.

STAT 107 is a popular option for freshman business majors’ computer science requirement or data science minor at the University. Business majors are also required to take BUS 101: Professional Responsibility and Business, where students learn various business basics: what to wear to networking events and how to make follow-up emails and presentations more “professional” by adding buzzwords.

Teaching assistants will tell students: “Trust me, just do it like this, and you’ll be fine.” Trust me, I was in BUS 101. I vividly remember my TA going over the AI policies for the course, saying that AI can be used as a “writing tool” to help brainstorm ideas, correct grammar and improve vocabulary.

“Congratulations (insert name)!” “I am thrilled to announce …” “I’m happy to share …” These are just some of the many sentence starters you’ll find on LinkedIn, a platform that students use for career development and “networking.”

Studies show that an estimated 54% of long-form LinkedIn posts use generative AI. While they may not all be AI-generated, they sure sound like it.

And it’s not just students. Five months ago, Ziegler, a 2024 graduate from the University of Maryland, started a LinkedIn post about her fellowship at The New York Times with “I’m excited to share.” Why do you sound like AI, Hannah?

While formulated “professional” language breeds cultural uniformity based on institutionalized standards, it also explains why so many emails from the STAT 107 undergraduates sound the same.

Let’s “utilize” the LinkedIn estimate and “ballpark” that half of the apology emails used generative AI. That means the other half of students could have indeed intended to write a “sincere” apology for their actions — except they felt compelled to say it the “professional” way.

Students using the phrase “I sincerely apologize” were making a trained attempt at professionalism.

And yet the reporters, as well as Vance and recent University alum Vinayak Bagdi, endorse the professors’ claim as the cold, hard truth: “That made it especially disheartening that some students had used A.I.,” Mr. Bagdi said.

Where is the perspective that the professors jumped to a conclusion too quickly?

Wade and Karle posted an Instagram video addressing the viral incident, generating over 1,000 likes. Where is the suspicion that the duo capitalized on their unproven claim to promote themselves and their recently founded data science curriculum at the University?

Beyond business majors, “this codespeak” surrounds University students in general.

The Career Center at Illinois publicly provides a list of “action words” to discourage more conversational tones. This can be a valuable resource to help strengthen students’ writing — not all buzzwords are bad. However, curricula and students treat lists like this as a solution rather than a tool. Students will frequently plug in as many buzzwords as possible just to sound more like a premium LinkedIn user.

The University’s mission statement is no exception to blasé business lingo, either. It uses words like “enhance,” “engagement” and “development.” This is not an attack on the University, but rather proof that these dull, indifferent words are everywhere.

Microsoft Outlook — the University’s email platform — also cultivates the use of AI in writing. In the top right corner of the Outlook screen lingers a Microsoft Copilot button. By clicking this button and using the AI bot, students can generate summaries of emails and essay-length responses within seconds.

How can you expect students not to use AI to write emails when the University’s email platform provides a shortcut to do so?

Even if proof arises that all students who said “sincerely apologize” used AI, this is not the full extent of the problem.

Vigdor, Ziegler and the University representatives in The New York Times article dismiss the reality that society and the University encourage students to sound like AI, as well as literally provide the opportunities to use it.

The reporters use a baseless, blanket-statement claim from the professors as a means to subtly criticize students for doing nothing but abiding by the suggestions and using the platforms provided by the University.

I took STAT 107 in Fall 2024. Professors Wade and Karle made it clear they did not tolerate the use of AI on assignments. This is understandable and acceptable, as AI fosters learning shortcuts and false truths. It reduces the benefits of learning from mistakes as well as from experienced professors and teacher’s assistants.

However, the introductory course is no stranger to AI. In fact, one of the units in the course, machine learning, is critical to the development of AI. The “factory” is discouraging its “workers” from using the products they are making. Strange.

The final line of the article is also unnecessarily targeted and confusing. It is a quote from Bagdi: “‘Out of any class at the university, why skip that one?’”

The reporters using this as the final line implies the purported yet unproven use of AI to write emails is just another incident of students being lazy. It does not focus on the greater institutional challenges and ethics at play. Rather, it chalks students’ (University-encouraged) AI writing up to indolence and disrespectfully dismisses STAT 107 as a “blowoff” class.

None of this is intended to attack professors Wade and Karle as purposely smearing UI students’ reputation. They are hard-working, educated and fun professors that do an incredible job encouraging an interactive and contemporary learning environment. Rather, their claim and The New York Times’ framing of it showcase a complex misunderstanding that students and institutions need to address.

The duo was right to call out students for “employing” futile language posing as sincere. They were also right not to punish their students for being victims of an omnipresent narrative that language can be replicated rather than representative of individual perspectives.

But perhaps professors, the University and The New York Times should consider the fact that students are using blasé business lingo to apologize for skipping class because they are not interested in a culture and curriculum designed to diminish their individuality.

Students using AI or AI-sounding language is not only a product of “professionalism” but also a rebellion against it. Students are, intentionally or unintentionally, telling professors: “Nah, I’m not going to waste my time using a voice you’re trying to silence.”

Alex is a sophomore in LAS.