Great films remind us that it’s impossible to define the human experience.

As humans, we’re addicted to trying to understand ourselves and our condition of being alive. These days, we funnel these efforts through internet discourse, needling our friends for self-evaluations and validations and, most importantly, taking in art.

Art has value because it is made by humans in the effort to understand themselves. Film is the most accessible and arguably most lucrative of the modern art forms, and no studio has perfected this understanding quite like Studio Ghibli.

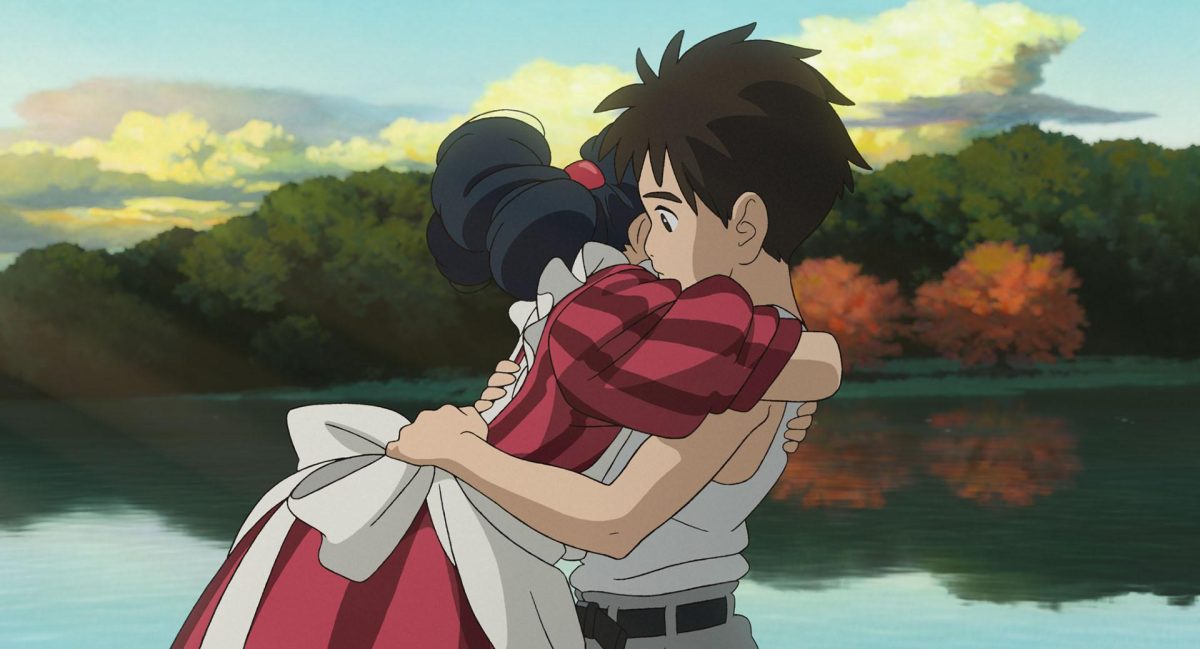

Last week marked the end of its annual back-to-theaters run, Studio Ghibli Fest. Stopping at our AMC 13 in Champaign, the Japanese animation studio, founded in 1985, upholds its prestigious and beloved place within world cinema. For its 40th anniversary, eight fantastic films were shown again in theaters, including the Oscar-winning “Spirited Away” and “The Boy and the Heron,” both directed by the esteemed Hayao Miyazaki.

Ghibli films, at their best, are masterpieces, and at their worst are still well-drawn and thoughtful films. The majority that comprise the best of their catalog delve into this understanding of the human experience through a unique lens — sidestepping direct answers in favor of pinpointing small moments that are universal to the human experience.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

It’s the aforementioned 2023 film “The Boy and the Heron” that gives little explanation to the audience for its colorfully realized world, choosing to ruminate on grief, adolescence and making one’s way in the frightening reality of growing up.

When we can’t understand something quickly, such as untangling the many metaphors of a Ghibli world, it’s frustrating. We often crave immediate gratification in our age of speedy communication and research. Perhaps it’s this laziness that has led to the startling rise of artificial intelligence in creative endeavors.

Quite the antithesis to the lovingly hand-drawn works of Miyazaki, AI art has been simmering to the surface of our technological zeitgeist for some time. I don’t mean to comment here on the wide benefits of AI’s use within other fields, like the ever-expanding and dire needs of institutionalized medicine.

I mean to only speak on AI’s use in creative endeavors. I make no effort to conceal my disdain for it, having been born with a comically oversized quill pen in my hand.

What is most startling to me, however, is just how easily we seem to have been taken in by this not-so-cheap magic trick. Sure, it’s a fun gimmick — asking ChatGPT to concoct a scene of a grotesquely realistic Squidward commandeering the LZ 129 Hindenburg.

But the writing and visual capabilities of AI are purely regurgitative — they only imagine what’s already been created. It’s in direct continuity with the ever-churning Disney remake machine and our fascination with controlling our understanding of ourselves.

Art has value because someone made it. Take the final release of Studio Ghibli Fest, “The Boy and the Heron.”

Every moment could fit beside a Monet — painstakingly hand-drawn frames of mysterious seascapes, frightening and adorable creatures and gorgeously-rendered details. From contemplative views of rain washing over rocks and spirits rising to the real world to be born, what makes it all so profoundly human is how little we understand it all.

We’re not treated to exhaustive exposition surrounding these fantastical worlds — no backstories, no lore and nothing to whet the curious whistle. We’re simply presented with these wondrous events and are encouraged to identify how they make us feel. We enter these stories as children, small and daunted by the enormity of what we don’t understand.

The nuance and empathy of “The Boy and the Heron” is, ironically, contrasted by AI’s once-popular trend of creating Ghibli-esque characters with all the studio’s visual aesthetics but none of its human imperfection or emotional vulnerability.

AI, in both visuals and writing, forgets the story. Much more than beautiful frames are found within Miyazaki’s filmography. Recurring trends in his films include fully fleshed and powerfully realized female protagonists, vehement anti-war sentiments and impassioned environmentalism. Amid its extraordinary fantasy elements, this art is truly grounded in the world of today.

Inversely, the constant self-refinement of AI-generated art and writing only holds as much value as the shattered pieces of human creativity it plunders. It has nothing to say.

However, we seem to be realizing this. Studio Ghibli Fest’s run through theaters this year was a massive success, with millions of tickets sold across the United States and a steadily rising number of participating theaters.

The festival has drawn audiences to both relive some of their favorite animated films and also experience cinema that they’d never quite imagined. This columnist’s own theater for September’s showing of “Spirited Away” boasted an encouragingly packed crowd on a random Wednesday night.

Humans will always choose the genuine over the artificial. There is a reason why beloved films like “Spirited Away,” “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Princess Mononoke” have enjoyed financial success in America, aside from their legendary pop culture statuses across Japan, China and Southeast Asia. They are accessible, bite-sized pieces of wisdom that both frighten and inspire us, as all good art should.

We give things value by paying them attention. Just as quickly as we allowed ourselves to become transfixed by the siren charms of AI, we can also turn back to art that reaffirms our lives and demonstrates real beauty, in all its imperfections.

Aaron is a senior in Media and LAS.