My earliest political memory takes me back to the not-so-fantastic eighth grade. It was a cold November morning in 2016, and I walked into my dimly lit school surrounded by the dejected, exhausted energy of my peers and teachers.

I didn’t understand the election’s consequences at the time. All I knew was that everyone in my blue-soaked world wanted the potential first woman president to win; that simply ended up not being the outcome.

Eight years later, I experienced the same phenomenon, despite the dimly lit halls of my middle school transforming into the neatly cut grass of my college campus quad. A female presidential candidate lost again, ironically to the same man, and my surrounding environs once more felt despondent.

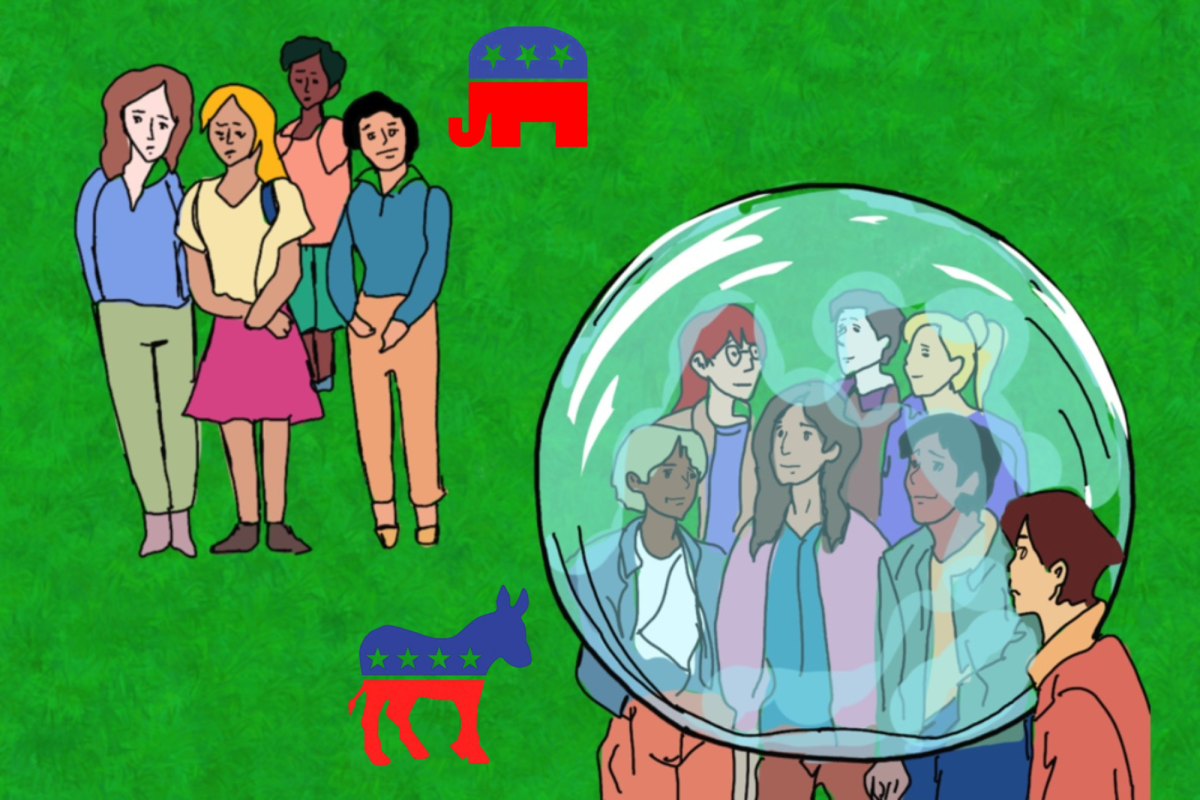

It took a repeat of this circumstance for me to realize I was caught in an echo chamber, receiving endless feedback loops where the same beliefs are repeated constantly, thus deluding their proponents’ notion that the belief is widely accepted.

Initially, it was difficult to understand how an election that felt so one-sided to me, just as it had in 2016, could result in Donald Trump not only winning the Electoral College but also securing the popular vote — a scenario that, according to FiveThirtyEight’s pre-election forecast, had only a 29% chance of occurring.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Brian Gaines, professor in LAS, said via email “that the (Kamala) Harris campaign … suffered from ideological blinders. Too many people lost sight of what swing voters want.”

Indeed, in a country where the outcomes of our elections are heavily influenced by a select few states, the importance of the voter base’s opinions in those states cannot be overstated and should be prioritized.

The distinction between the Harris and Trump campaigns, according to Gaines, was that “(Trump’s) campaign played up trans issues and immigration down the stretch, and those were both winners for him regarding on-the-fence voters. Harris played up the ‘threat to democracy’ argument that is a big winner with strong Democrats, but not with moderate independents.”

In other words, since the Trump campaign centered around issues important to undecided voters, he was successful in his bid to return to the White House. Meanwhile, Harris and her campaign believed painting Trump as a threat to democracy would be their campaign’s most successful claim solely because of the reactions in stronghold Democrats.

Exit polls taken the night of the election corroborate Gaines’ claims: Independents were much more likely to side with Republican issues, such as immigration and the economy, rather than with the issue of the security of democracy, which was the largest among Democrats.

The Harris campaign, in this facet, caved into the walls of their echo chamber by repeating the trope that Trump was a threat to democracy. Since that issue, as Gaines pointed out, was so popular among Democrats, the Harris campaign was effectively blinded and chose to brand themselves around it.

Losing sight of what matters to the average swing state voter is a recipe for disaster in a political campaign. The Democratic Party struggled with this in their representative’s campaign, and they are facing the consequences.

Aside from the political advantages of breaking down the walls of the tallest echo chambers, there are personal benefits for us as college students in ensuring we listen to as many voices as possible — including those outside our own echo chambers.

Something must be learned from the missteps of the Harris campaign and the continuous shell-shock of Democrats if we want to conquer the physical limits of echo chambers. That duty falls on everybody, including students on campus.

For example, Champaign County was won by Harris by the largest margin of almost any other county in Illinois, second only to Cook County.

While that contributed to the morose tone on campus in the days that followed the election, perhaps we, as a campus population, can work toward understanding the world beyond our campus while retaining our political beliefs.

As Nicholas Grossman, professor in LAS, said via email, “Every community, however it’s formed … is to some extent an echo chamber.” However, the true challenge lies in recognizing the limits of our perspectives and actively seeking to engage with those outside them.

After all, that’s what contributed to the loss on Harris’ part. Speaking for myself, I hope in 2028, whatever the outcome, the energy in my immediate surroundings will provide a slightly more diverse perspective.

George is a senior in LAS.