Opinion | Centrism is a failing strategy

Photo Courtesy of Michael Stokes

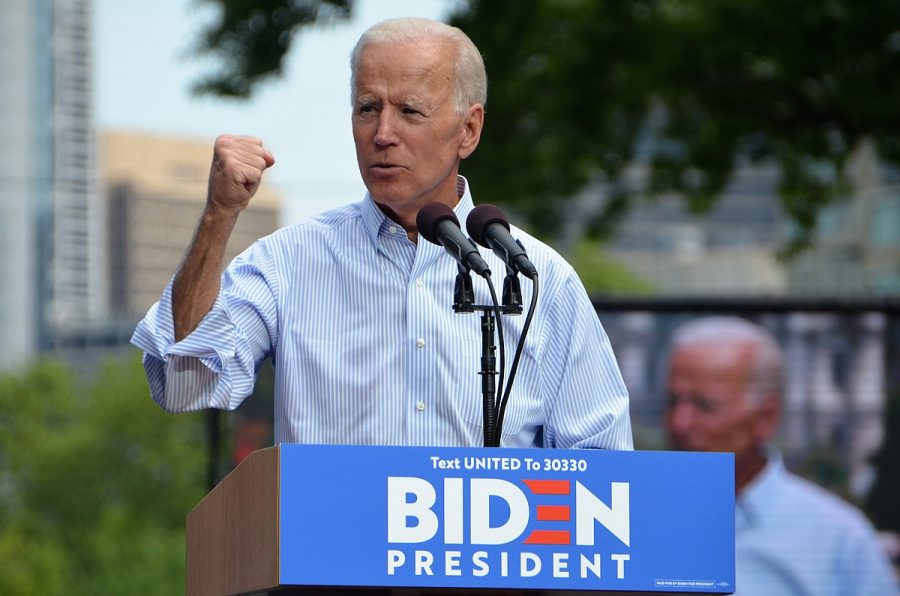

Former Vice President Joe Biden’s kickoff rally for his 2020 Presidential campaign

Sep 11, 2019

As Democratic hopefuls jockey for the party’s endorsement for the 2020 presidential candidacy, the divided Democratic Party must decide yet again whether to proceed with a progressive candidate or a centrist one.

Through media and party messaging, the party has seemed frightened by the prospect of a progressive candidate winning the nomination and have encouraged voters to choose someone with ostensible appeal to more voters — a moderate.

The Democrats nominated moderates like Barack Obama and conservative Democrats like Bill Clinton. They expected the captured groups of voters to the left of center to eat their vegetables and fall in line. In 2016, then radical candidate Donald Trump won an unprecedented victory for manifold reasons, but one was that his main opponent, Hillary Clinton, was a moderate. As Democrats conduct the routine autopsy report on their loss, one conclusion should be painfully unambiguous: Centrism is a losing strategy.

Clinton lost for a variety of reasons surrounding personality, career record and shoddy campaign strategy. She also struggled as a moderate. Some progressives, lacking enthusiasm for her or her policies, proved that the liberal wing of the party would no longer be a guaranteed monolith.

People always want change. Being a centrist candidate often means supporting the status quo and lacking real beliefs in change that should be brought to the country. Even if a voter is doing well under the status quo, he or she will always want it to be better. People yearn for change that could help them achieve the American dream, regardless of their current socioeconomic status.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Furthermore, politics is an emotional field. Voters love passion. It is difficult, however, to be passionate about centrism — especially when much of it hinges on unenthusiasm toward both sides. Candidates who promulgate the status quo find it difficult to inspire passionate supporters the way fringe candidates can.

Similarly, revisionist candidates have a much easier time staying on message because of the radical change they propose. Center-left and center-right candidates often bicker about who can best do what officials have been doing, but extremists can more easily retain their message and unique ideas while seeming like the country’s sole Messiah. They carry more political convictions that can potentially scare off centrist independents but also have a chance of exciting a large turnout of impassioned ideologues.

Additionally, it is a partisan’s duty to propose and support ideas that may be seen as extreme. Support for the extremes may not be good for bipartisanship, or unity, but from a prudent standpoint, it is healthy for the party. Fringe candidates help to keep “extreme” ideas within the political mainstream.

Senator Bernie Sanders proposed “Medicare for All” during his 2016 presidential run, an idea that was berated for being too radical. Ignoring the ahistorical ignorance of that statement, “Medicare for All,” is now within the realm of mainstream political thought, because Senator Sanders gained a platform and media attention and persevered in the face of those who called it extreme.

Furthermore, according to historical trends, one of the two major parties will capitalize on the opportunity to double down on their extreme whenever one party moves closer to the center. If one party moderates its stances and the media attempts to maintain its image of fairness in depicting both sides, the “center” of American political thought shifts in the direction of the other party. Ergo, moderating concedes ground to the other party, like a team losing in a game of tug-of-war.

Finally, centrism is no longer the popular ideal it used to be. The “enlightened centrist” is often satirized as a smug political layman who does not have a stance on any issue and prioritizes above all else finding middle ground on issues in which there just is not. This negative depiction of the modern day centrist has helped to foster this reluctance to support one.

The only thing centrists have to contribute is the potential for unity in a divided country. But voters seem to prefer meaningful change that agrees with their ideology over unity every time. The amount of Bernie–Trump voters in 2016 demonstrates that many people will vote for someone with ideas on how to change the country in profound ways.

This isn’t an impassioned cry for radicalized partisans to feel morally justified in their position. It is an acknowledgement that good political strategy is moving away from the center. It is hard to be the poster child for boring, old middle ground compromise in a divided country. It is difficult to take down the romanticized fringe candidate who will solve all the countries’ problems.

Status quo Joe Biden at a recent campaign fundraiser said to rich donors that during a Biden presidency, “nothing would fundamentally change.” And well, this is not exactly a campaign slogan to inspire the disgruntled masses.

Andrew is a sophomore in LAS.