Opinion | Recognize biases, diminish political division

Nov 10, 2020

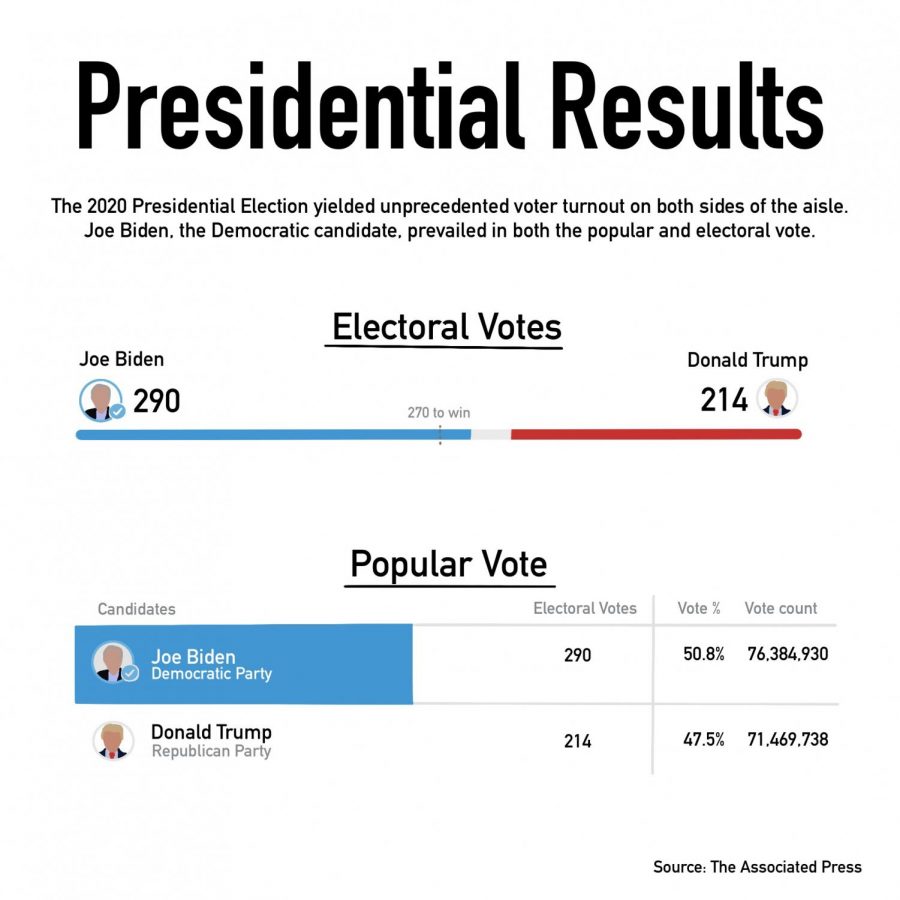

Well, it came and it went. The 2020 election for all intents and purposes is over. Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. is the President-elect of the United States. I received this news with a sigh of relief for many reasons, the most important being the roller coaster of the last several months is coming to an end.

In the four years since the 2016 Presidential election, the division in the United States has only deepened. If you’re a part of Generation Z, which 60% of students at the University are, odds are 2016 was the first time you were old enough to be cognizant of the elections, candidates and maybe even some of their policy implications.

As 2016 was the first time many young people tracked presidential politics, one may be apt to think that particular election represented “normal politics.” It didn’t. We are a nation more deeply divided now than at any point in recent history.

For example, some people are actively itching for a second civil war. Right-wing insurrection groups who look like they’ve raided their local army surplus stores have made their presence known at left-wing protests, leading to a series of deadly meetings and heightened tensions. It’s also been disconcerting to see businesses around the country having to board up in anticipation of post-election violence.

So, how can we decrease this division? One answer has been to vote Trump out of office. Joe Biden has made note of this, promising via Twitter, “You won’t have to worry about my tweets when I’m president,” for example.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

However, love him or hate him, voting Trump out of office won’t magically return life ‘back to normal.’ Trump is often purposefully divisive with his careless rhetoric and vilification of his political opponents. But he is a symptom of the nation’s divisiveness, not the disease.

In the 1980s, scientists began analyzing twin databases to understand nature versus nurture and its relation to politics. They concluded that siblings grew up to have very similar political preferences to one another regardless of whether they were raised together or not. This finding signifies the way you lean politically may not be as much a rational choice as a product of your genetics.

The next question to answer is, how can we use this information to heal the divide in our country? We need to build bridges to our political adversaries.

Karen Stenner, a political psychologist, says the prescriptions to healing are different for the left versus the right. The left, she says, can consciously help reintegrate conservatives into shared institutions where they face a hostile climate such as academia or the mainstream media.

The right can help by not retreating from these shared institutions to create murky alternatives which lead to the rise of websites like Breitbart, InfoWars and the Gateway Pundit. Right-wing individuals must also combat intolerance within their own ranks.

In what was an overtly negative election cycle, it’s important to separate your feelings about a particular candidate from your feelings about said candidate’s voters. One helpful metaphor NYU Psychology Professor Jonathan Haidt uses to explain the public’s close-mindedness is “the matrix,” the idea that each voter exists in their own political reality as dictated by their choice of media.

Haidt goes on to say when living in your own matrix, everything appears in black and white and is subsequently easy to label: “They’re socialists,” “They’re racists,” “They’re the worst people in the world.” You feel you have all the facts necessary to back those labels up.

However, somebody in the next house from yours is living in a different matrix, in a different reality. They see a completely different set of facts, different threats to the country.

Haidt’s analysis has concluded both sides are right. Each side, though able to recognize the threats to democracy this country faces, is wholly unable to understand the perspective of the other side.

The antidote to how this country views politics is to not immediately assign malicious intent to the actions of one’s rivals; doing so is often one of the biggest obstacles toward unity.

Don’t buy into the myth that your political adversaries hate you and want what’s worst for our country simply because their values differ from yours. Instead of trying to change their values, reach across the aisle and try to understand them. Martin Luther King, Jr. said it best: “Build bridges, not walls.”

Grant is a junior in LAS.