A long way to go

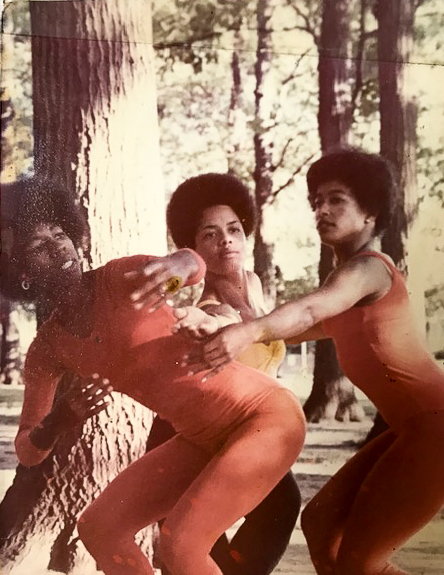

Connie Eggleston (left), who graduated from the University of Illinois in 1972, dances with friends in the 1960s for the Champaign studio “Artist in Motion.”

Feb 11, 2019

A few short months after Project 500, an initiative to recruit more black and brown students to the University, was implemented in 1968, minority students claimed they were still being discriminated against by administration through housing, funding and lack of equitable resources.

Although students planned to meet with campus officials to discuss their concerns, it was not anticipated this would result in the largest campus arrest in United States history.

The arrest

Like every start of an academic school year, University students return to campus with anticipation and excitement for the new year, purchasing textbooks last minute, decorating dorm rooms and planning out schedules.

However, some students were fighting for equal opportunity on campus.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Minority students were upset about the change in their housing accommodations, as they were relocated from staying at Illinois Student Residence Hall to spaces not suitable for living like sewing rooms, laundry rooms and lounges.

Connie Eggleston, a 1972 alumna, and her peers wanted to meet with administration to discuss how to remedy the circumstances. In doing so, the black students planned to march to the Illini Union and host a peaceful sit-in to attract Chancellor Jack Peltison’s attention to discuss their demands.

On Sept. 10, 1968, around 7 p.m., the sit-in began.

The students gathered and occasionally gave speeches regarding their concerns. Eggleston said they had no intention of causing any problems, but they wanted to make sure the black students’ voices were heard.

“The students were socializing and playing games, nonviolently, when administration showed up. The students were informed that they will get the chancellor and gave the students permission to be in the building,” Eggleston said.

Eggleston also said University officials addressed the students multiple times to say the chancellor was on his way. But, he never showed up.

Students were asked to leave the Union because of a mandatory student curfew at midnight. However, no one left.

At the Project 500 panel, Patricia McKinney Lewis, ’73 alumna, said as the night progressed, students became fearful for their lives.

“Around 1 a.m., we were told we could not leave because there were people outside of the Union who could harm us,” she said. “I could hear glass breaking, but (I) did not see any damage.”

At 2 a.m., students were told it was safe to return to their dorms. But as the students were leaving the Union to return home, they were instead led to a police paddy wagon.

Over 240 students were arrested and taken to local jails for partaking in the sit-in.

Eggleston’s feisty and strong-willed personality did not cease once the policemen showed up, but rather allowed her to use her platform to combat the mistreatment. Instead of going to jail like many of her peers, she jumped out of the paddy wagon and walked back to her dorm.

Eggleston said although it was disheartening the sit-in wasn’t successful, students left the Union peacefully.

After the arrest, black student involvement increased as tension grew on campus within the faculty, staff and administration.

Before the arrest

Like many students on campus, Connie Eggleston had every intention to succeed when she got to the University. Encouraged by her brother, she decided to put her modeling career on hold and pursue her education.

However, when she got on campus, it was not what she expected.

“When I first came here in 1966, there was about 33,000 whites and less than one percent black, so there were only 100 something of us on campus,” Eggleston said.

Recruitment and retention within the black and brown community was an area of concern for students. The issue stemmed from their lack of housing.

Black students were not able to live in residence halls due to high pricing and lack of accommodation. However, different groups on campus, like Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. and Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. provided housing for minority students.

Even the former director of the black cultural center, Bruce D. Nesbitt, helped house students at his campus home to keep them from walking over two miles to class.

Valeri Ann Nesbitt Howard, Bruce D. Nesbitt’s daughter, said many of the students that lived in her home became like family.

“It was really cool because there were different students that we’d house every school year, and just growing up under his jurisdiction (brought us closer).”

One thing Eggleston noticed was the lack of campus resources and African-American education on campus. She said the University “didn’t have any cultural activities for blacks besides parties at the Union.”

Although she faced several obstacles at the University, education hindered her the most. Eggleston said she questioned her professors’ intentions in teaching students. She recalled her teachers marking up her papers and not having a good relationship with them.

“It was very disheartening,” Eggleston said. “I was not discouraged (and) I kept going, but that did not help me with my grade point average. It was almost like we felt like they were trying to flunk us out. They wanted us out of here.”

Yvette Long, ’72 alumna and clinical supervisor for the College of Education, said it was a culture shock for black students on campus and her academic life.

“The professors and instructors were hesitant teaching us because they didn’t think that we were capable of being part of the University,” Young said. “Other obstacles were your peers. Ignorance was a big part of the obstacles we had to face both in the academic community as well as the community of Champaign-Urbana.”

Due to the lack of support from her professors, Eggleston withdrew from the University. But she did return back to school with the help of her brother, James Eggleston, one of the originators of Project 500.

Project 500 was created in effort to increase minority enrollment at the University, and as a result, more than 500 students were admitted into the institution.

“After the punch, that’s when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. That’s when my brother James Eggleston and the other upperclassmen marched to the chancellor and others from the community and said ‘enough is enough … we need more black students down here,’” Eggleston said. “That is how the name Project 500 came about and how I got back in.”

Project 500 and the demands of 1968

After months of recruiting students in larger cities across the country, 565 minority students were admitted into the University. In fall 1968, among 25,347 students, only 852 students were black. Throughout the years, the rate of African-American students on campus has increased, and it’s benefitted other minority groups as well.

Visiting Faculty and University Archives Resident Jessica Ballad said this initiative recruited roughly 470 black students.

“When you hear that there (were) 565 black students, you were under the assumption that it was only black students,” Ballad said. “It is very possible that there were more than 500 students that got in that year. However, they were not considered Project 500. It was a program and qualifications that you had to apply for.”

As there were more underrepresented students, the University could not accommodate all of them. They assumed the recruiters would only be able to get 250 students from the initiative.

That number doubled and there was no plan in place from the administration for these students.

Long recalls the moment she knew she was going to be treated differently from other students as she was placed in a University laundry room as her housing.

“That was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Long said. “We knew that we’d be treated a little different from the (first) week that we were here, but when we realized that we didn’t have a place to stay, a place to eat … We were all 17-year-olds … The security blanket was taken away from us.”

Within the next week, these students demanded more equal rights, leading to the sit-in and the arrest.

After the sit-in where the chancellor bailed on the students and police arrived to arrest them, students were still determined to make a better experience for themselves at the University.

After the arrest

Despite the arrest, the Black Student Association wanted to ensure its demands were met. The retention rate for African-American students jumped from 852 students to 1,025. There were more African-American classes, and in 1969, the cultural center opened. Under the supervision of Clarence Shelly, the director of special education opportunities, a faculty and staff were commissioned for the center.

According to its website, the Bruce D. Nesbitt African-American Cultural Center has two major goals: “to encourage within African-American students a growing sense of pride and dignity based on their rightful cultural heritage” and “to promote campus-wide understanding of the unique contributions of African-Americans to the life and culture of the campus, the nation and indeed the world.”

This aligned with the views of the former director of the cultural center, Bruce D. Nesbitt, who was a large influencer in the advancement of the African-American community on campus.

Howard reflects on the impact her father had on the cultural house and even her own life.

“When they say, ‘It takes a village,’ that’s exactly what (the center) was: (students) going to the University of Illinois and being active in their groups and even Project 500,” Howard said. “When you have people who encourage you, motivate you and care for you, that’s part of what molded me to be the person I am today.”

Because of BNAACC, opportunities were created for other minority groups to get their own cultural centers as well, like La Casa Cultural Latina, which opened up in 1974. Jorge Mena Robles, director of La Casa, said without the black house and student activism, other cultural houses would not exist.

“When we think of BNAACC, that was the first campus cultural house, and it’s because of students coming together (that) they realized there was a huge need for spaces for them that felt equitable,” Robles said.

Howard said despite the changes that have happened throughout the years at the center, it was important her father’s vision was carried out to this day.

“This is about community,” Howard said. “My father was very passionate about community. He always wanted to bridge the gap and wanted to bring (Champaign and the University) together. That was what his vision was, (and) he was profound on it. His works (speak) for himself.”

Read part two in print and online Thursday.

Editor’s note: Taylor Howard is involved with several black organizations at the University. She is the president of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., Alpha Nu Chapter and the president of 100 STRONG.