Tap water filter aims to remove potentially harmful pharmaceuticals

Nov 15, 2018

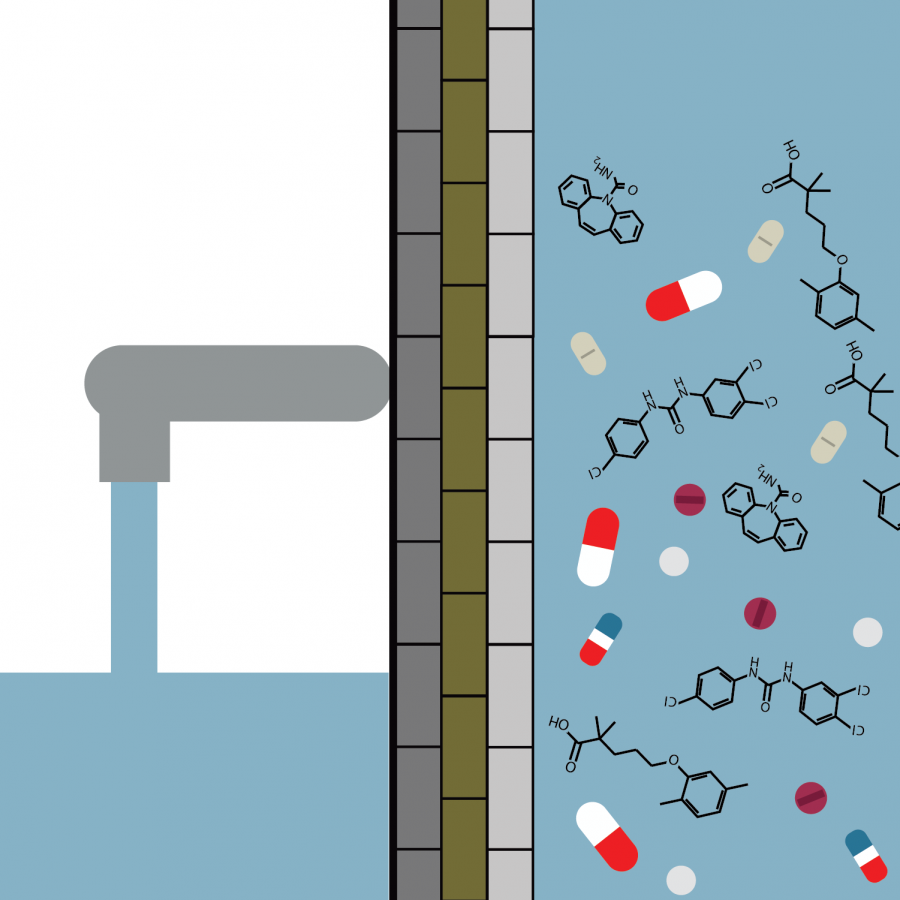

Tap water: It’s a norm in households around the world, and people don’t often give it a second thought after turning on the faucet. However, what happens when the water that comes out is contaminated?

Dipanjan Pan, associate professor in bioengineering at the University, is working on a way to remove those contaminants — pharmaceuticals — from tap water using a specialized filter.

The filter is separated into four layers, each of which serves a different purpose in removing contaminants. The primary part of the research has been on the first layer, which contains a carbon compound that collects the pharmaceuticals from the water. It’s been labeled a pharmaceutical-nano-carbo-scavenger, or PNCS.

This has evolved from Pan’s previous work, which focused on cleaning up crude oil after spills. A similar science was used: A particle would capture what needed to be removed. In the case of crude oil, the particle would “capture all the hydrocarbon” that was present in the oil, and once that happened, it would form clusters that could then easily be cleaned up.

Pan called the particle used in the tap water a second-generation particle. “It’s kind of a very expected and logical extension of our previous oil spill work,” he said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“The particle that we used for oil spill remediation, (it’s) the same type of particle but with a different shell around it that is capable of capturing all these materials,” Pan said.

There are three other layers in the filter. The second contains activated charcoal, which removes heavy metals. The third is fine sand, which removes small impurities. Finally, the fourth is sand granules, which removes larger particle-sized contaminants.

Pan does not work alone on this research. There are seven other researchers involved in the project, one of whom is Wei Zheng, senior research scientist at the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center who joined the project in 2015.

Zheng said Pan’s part of the team focuses primarily on nanoparticles, whereas his own team works on “emerging contaminants,” which are chemicals detected within drinking water that have currently unknown effects on human health.

The research currently focuses on three different drugs: carbamazepine, gemfibrozil and triclocarban. Carbamazepine (commonly known as Tegretol) is medication used to prevent and control seizures; gemfibrozil (commonly known as Lopid) is used to lower fats; and triclocarban is common in bar soaps, according to RxList.

According to the research, the PNCS is capable of removing more than 99 percent of the gemfibrozil and triclocarban, and more than 70 percent of the carbamazepine found in tap water.

“What we are showing is that after the treatment … some of these drugs are completely taken from the (water),” Pan said. “They are completely scavenging, and (there is) greater than 99 percent removal.”

While the removal of the actual pharmaceuticals is important, the research also prioritizes ensuring that the removal process is equally safe for humans and the environment.

“These particles are biodegradable, and that gives a unique opportunity to utilize these particles,” Pan said. “They can be degraded by certain kinds of enzymes that are present in our bodies.”

Including the biodegradable particle in tap water removal means that once the water passes through the filter, the pharmaceuticals will be removed and there will be no negative effects on humans through exposure to the particle itself. This is in contrast to the use of toxic and environmentally harmful materials in oil spill-cleaning procedures, which was the catalyst for this project.

“They would put some material in a plane, and they would start spreading it all over the oil spill,” Pan said. “It’s really causing harm to the sea life.” Using biodegradable particles in the filter avoids a similar problem.

So, how do these pharmaceuticals end up in tap water in the first place?

Pharmaceuticals enter tap water primarily through people flushing them once they’re unused or expired.

“This is not a proper way of disposing those materials,” Pan said. “Those (pharmaceuticals) can end up in soil, and from there it can come back to the drinking water source.”

The Food and Drug Administration currently recommends flushing 15 different types of medication after use, including drugs like morphine, methadone and oxycodone. According to its website, the “FDA believes that the known risk of harm … to humans from accidental exposure to certain medicines, especially potent opioid medicines, far outweighs any potential risk to humans or the environment from flushing these medicines.”

The FDA published a paper in 2017 analyzing the risks associated with its 15 recommended flushable drugs. According to the results, “these medicines present negligible risk to the environment.” However, the FDA said “some additional data would be helpful for confirming this finding for some of these medicines.”

According to Fatemeh Ostadhossein, graduate student in bioengineering at the University and one of the team members, there are many pharmaceuticals that may be risky.

“There are about 3,000 different substances used as pharmaceutical agents with concern surrounding them about their effect on the drinking water, development of bacterial resistance and effect on the natural ecosystem,” she wrote in an email.

While the 15 recommended flushable drugs are not the focus of the research right now, Pan sees a future where the science behind the filter could expand to include more than just the currently tested drugs.

Pan said he ideally wants the filter to become a household item.

“We think that in the next couple of years, we can kind of take it to the next level,” Pan said. “The next thing could be that we start scaling it up and we try to see how the performance of these materials are working at a very large scale because that would be a very critical thing to test.”

The paper documenting this research was recently accepted by the Journal of Materials Chemistry A, which is published by the Royal Society of Chemistry.

“We want to see how new materials can help us solve some of these burning issues in today’s society,” Pan said. “At the same time, we just don’t do something just for the heck of it. We want to do something that is meaningful and that would have a long-lasting effect on mankind.”