Experts, advocates express need for Black mental health resources

Jan 19, 2022

For many, COVID-19 has been a wake-up call that has revealed some of the everyday things and experiences people often take for granted.

But mental health professionals and advocates said that in the medical field, COVID-19 has been a stark reminder of the inequalities and barriers that minority communities face.

For example, people of color have had higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death due to COVID-19 than white people.

When it comes to mental health in the United States, about 13% of the U.S. population identifies as Black or African American, and of those, 16% reported having a mental illness in the past year.

That’s about seven million people.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Within the Black community, 63% of people believe that having a mental health condition is a sign of personal weakness.

Karen Simms, founder of the Trauma and Resiliency Initiative in Champaign-Urbana, said this could be attributed to the way wellness is viewed for African Americans historically.

“Wellness wasn’t a strategy that we were allowed to have,” Simms said. “So, lots of things got pathologized.”

This stigma, Simms said, has historical roots in slavery and other periods of inequity where Black people weren’t allowed to be mentally healthy.

“Part of it is giving language to an acknowledgment that there have been some structural and systemic barriers that have not allowed for us to have this whole concept of mental health or understanding of mental illness,” Simms said.

She also said that historically, Black folks tend to have a strong sense of community and faith. She said there’s also a narrative that to be Black is to be strong and resilient, especially in the face of pain or struggle.

This description mixed with a connection to faith, she said, leaves little room for being able to experience mental health struggles.

“To be somebody who is not well – you could internalize that it means that you’re not a representation of healthy Black behavior, that means that you’re weak and that you’re vulnerable and that something is wrong,” Simms said.

She said this stigma carries into the medical field because it led to a period of time where medical professionals didn’t view Black people’s unwellness as a mental health issue.

This, she said, then led to a wrong diagnosis or no diagnosis at all, which then may have led Black people to self-medicate since they didn’t receive proper medication.

“It’s so much easier to say, ‘Uncle Johnny drinks too much’ than ‘Uncle Johnny has depression’ or ‘Uncle Johnny is anxious,’” Simms said. “It might be nice to think about it more of a moral failure than a structural need.”

Recently, Simms said Black mental health is also associated with generational trauma that can come from witnessing acts of violence.

In the United States, Black people are three times more likely to be killed by the police than white people, and in 2021, Black people were 27% of those killed by the police despite only being about 13% of the population.

This type of violence, she said, along with escalating rates of violence in general among and to Black people, can lead to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, which both fall under the definition of trauma.

She said these cognitive feelings can manifest physically as well.

“Witnessing somebody be murdered increases your stress response, so it gives you more stress hormones,” Simms said. “If you feel like there’s nothing you can do to keep yourself safe, then it leads to some feelings of hypervigilance.”

Feelings of disempowerment, she said, can affect dopamine and serotonin levels that then impact the heart and the brain, which can look like a bunch of different mental health needs.

Other people, such as teachers, she said, might not view this behavior as adaptive to what a child may be experiencing or seeing but rather as pathological behavior that needs to be disciplined.

This can then lead to what researchers call the punishment gap.

Black students in middle school and high school, for example, were four times as likely to be suspended as white students.

This, Simms said, could also be due to implicit bias, which is described as discriminatory or racist behavior against someone else without consciously doing so.

Simms said one way this can be avoided is by viewing experiences from a trauma-informed lens.

“We always say that when you see somebody do something, the question is not what’s wrong with them, but what’s happened to them,” Simms said.

Basically, she said, be curious rather than judgmental.

A whole other piece of Black mental health, Simms said, is intersectionality, which means taking into account all aspects of one’s identity and acknowledging the many types of oppression one may be facing.

“The more you’re impacted by structural inequalities and inequities, the more likely you are to have a mental health need,” she said.

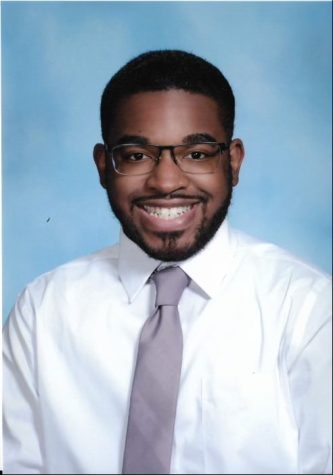

Justin Michael Hendrix, community engineer and creator of local advocacy group HITNHOMEBOY, works regularly with Black and brown communities, as well as LGBTQ+ members.

He said Black people that also identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community face discrimination within the medical field at much higher rates than Black people who don’t identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community.

“I believe that when it comes to mental health, we have to always look at the data,” Hendrix said. “We just can’t look at data as a collective. We have to break it down as demographics to make sure that we’re actually doing the real work.”

According to data from 2012 through 2017, in the United States, 15% of Black non-LGBTQ adults are uninsured, while 20% of Black LGBTQ adults were uninsured.

Data also shows that Black LGBTQ+ people face discrimination within the medical field.

Eight percent of gay, lesbian, bisexual and queer people reported that a doctor or other health care provider refused to see them because of their perceived sexual orientation, while that number was at 29% for Black transgender people.

Hendrix said this discrimination as well as historical events, such as the Tuskegee Experiment and the Henrietta Lacks cancer cells experiment, where researchers experimented on Black bodies for science, has contributed to the hesitation of Black LGBTQ+ people to seek medical care.

“How do we use these Black bodies for research, and then yet still, you want us to have trust in the medical fields to know we’re doing the proper work and research?” Hendrix said.

He said where we are right now, it’s hard for him to picture Black LGBTQ+ people being fully comfortable seeking medical aid.

“I can’t imagine a trans person coming into a health care environment believing they won’t be discriminated against,” Hendrix said. “Even as a Black, cis-gender male, I can’t see myself going into a field and not being discriminated against either.”

He said one of the steps to remedying this issue is through education about the history of some of the institutions we interact with on a daily basis.

When thinking about police brutality, for example, Hendrix said we need to start understanding the history of police brutality just as we understand the history of racism.

“They go hand in hand,” Hendrix said. “We know that policing came straight from out of the slave movement.”

He said when thinking about the history of the police in the “slave mastermind frame,” the police’s purpose is “to only protect property, not people, property and privilege, not people who are served or even close to getting privilege.”

He said taking this into account can help people understand some of the traumas that play out over time as a result of the impact of racism in the United States but also as a result of the lack of mental health resources for Black people.

But with the appropriate programming, he said, we can start to make changes.

“That way, we know that it’s assertive, it is expressive, but also it’s impactful to where people understand what’s going on at hands here,” Hendrix said.

He also said we need to be having conversations about different demographics, specifically when talking about mental health.

“There’s different demographics in every situation that we have to serve,” Hendrix said. “When we really come together to do the work properly in our demographics, data can get driven to then get the proper funding to get the work done.”

At the University of Illinois, Black students are already working to get this kind of work done.

Kyle Semper, a senior psychology student with a concentration in clinical community, is a paraprofessional at the University of Illinois Counseling Center and a part of Sankofa, the Black student outreach group within the Counseling Center.

Semper said educational resources like Sankofa, are steps toward reducing implicit biases and creating a more inclusive environment.

“I think definitely one of the most important things is doing more research and also giving people more information, so they’re not as fearful and kind of misunderstanding of the topic,” Semper said.

Sankofa, he said, informs Black students about mental health resources they might not know exist on campus. For example, Semper said a lot of students are unaware that the University has Black counselors.

“That kind of turns people off to think that they can’t reach out for help if they feel that they need it, but that shouldn’t be a deterrent,” Semper said.

He said mental health outreach that is geared toward Black people can help give the community a sense of agency since not every culture faces the same issues.

“There are specific situations that we as people have to face, and it should be understood how our experiences are different from other people’s, and it should be recognized and treated differently,” Semper said.