When a veterinarian delivers a cancer diagnosis, the news can bring a harsh reality that effective treatments could cost thousands of dollars, or may not even exist. Here, at the University, the Anticancer Discovery from Pets to People theme challenges that reality.

The ACPP research theme operates within the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, involving several professors from the College of Veterinary Medicine, and is designed to accelerate drug discovery. This initiative offers fully funded experimental anticancer treatments to dogs and cats with naturally occurring tumors that translate to clinical trials in humans.

Leading this work is Paul J. Hergenrother, ACPP theme leader and professor in LAS, and Dr. Timothy Fan, professor in Veterinary Medicine.

A mix of empathy for pet owners and curiosity fuels Fan’s drive to find an effective drug.

“As a veterinarian, there is a lot about compassion in helping that pet and, more importantly, really trying to provide hope and realistic expectations for pet owners,” Fan said. “The scientist piece is where intellectually I get stimulated. The ability to think about what are ways to … develop new therapies to fight this disease.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Standard drug development often relies on mouse models that fail to predict how drugs behave in humans, according to Fan. In contrast to mice, Fan further mentioned that dogs and cats develop cancer spontaneously, mimicking the way tumors form in people.

Fan said this biological similarity makes them superior “pre-translational models” because they offer a more accurate prediction of whether a therapy will work in a real-life setting.

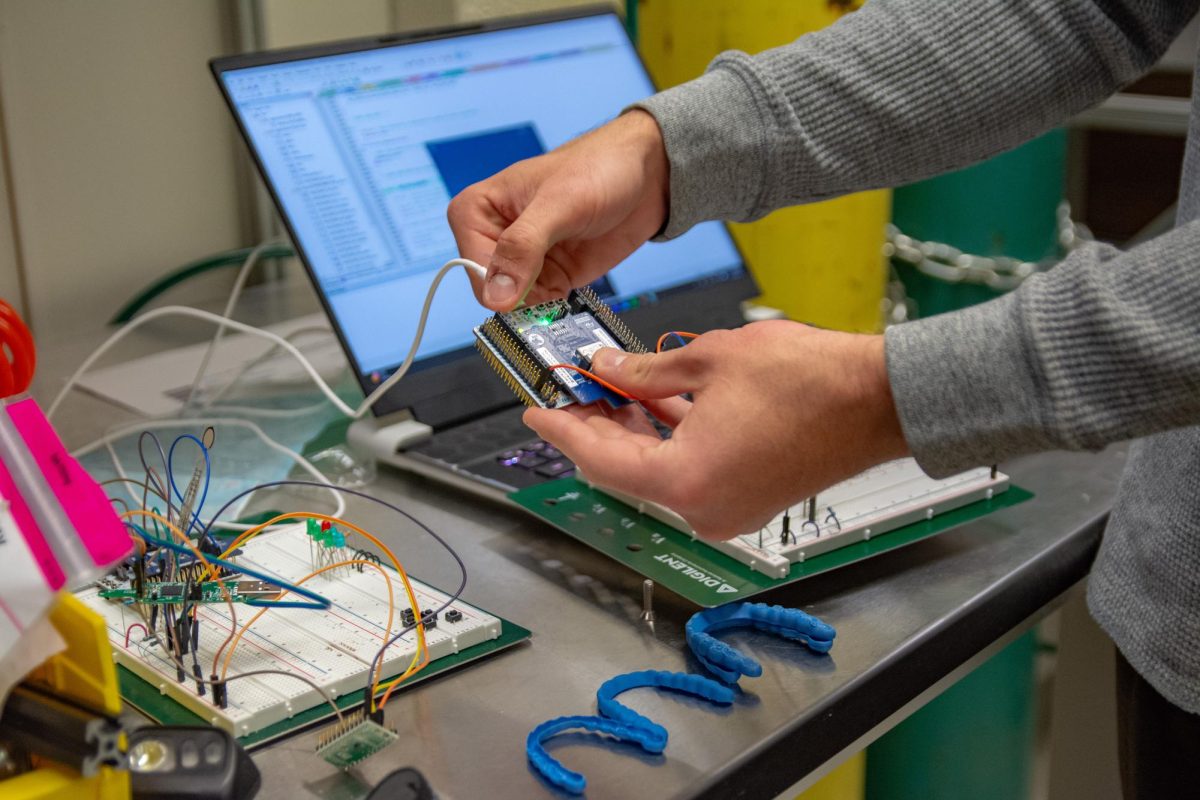

Because of this physiological similarity, ACPP can identify effective compounds in pets first. These compounds — small molecules with anticancer activities identified by high-throughput screening — are then tested for their safety in dogs and cats. Fan said the team ensures that only the treatments with the “greatest promise” advance to human trials.

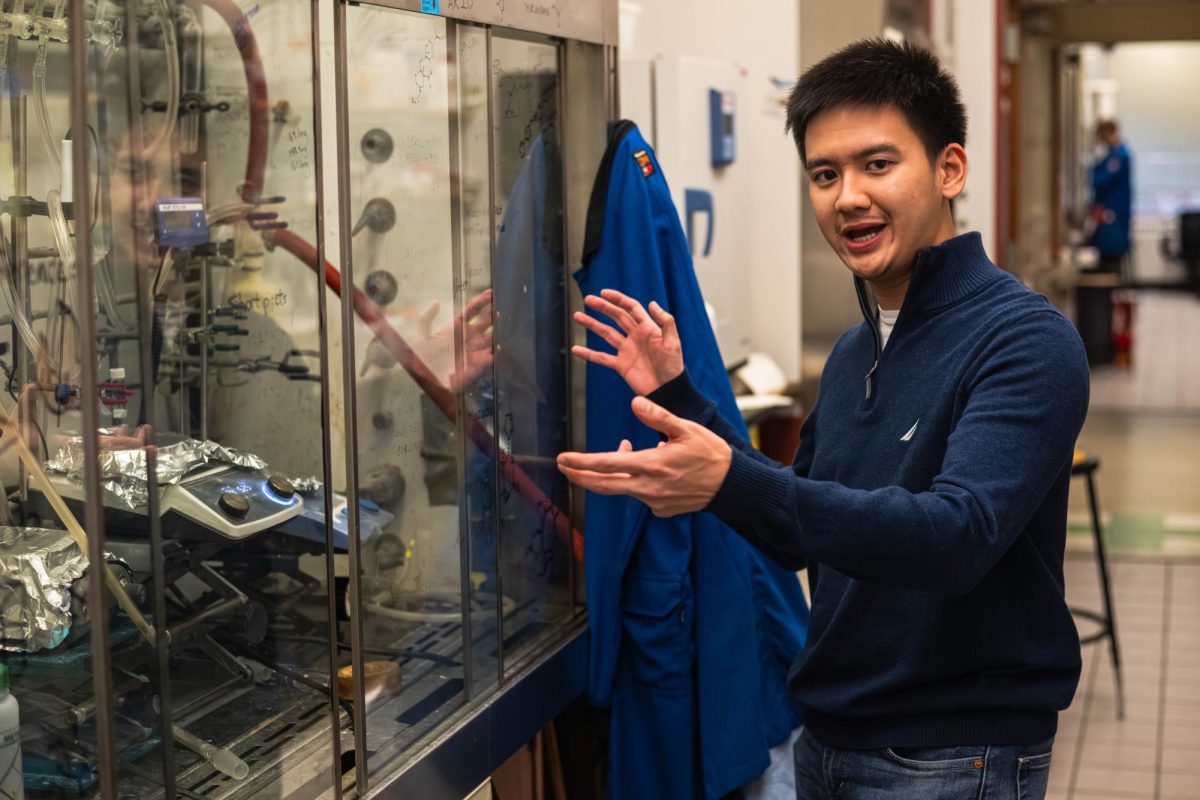

The program is already producing results. Researchers like Kyle Abo, graduate student studying chemistry, are developing these next-generation compounds.

“I actually took (a) compound and tested it against cancer cells and was actually able to see it kill cancer cells,” Abo said. “It was pretty inspiring for me to see a molecule that was made by my colleagues … and see it exert its anticancer effect and killing.”

The research team has treated more than 50 pet dogs with cancer through the discovery of PAC-1, a procaspase-3 activator.

PAC-1 works by targeting a protein called procaspase-3 that is often abundant but dormant inside cancer cells. The drug acts as a molecular key, unlocking a hidden self-destruct sequence that causes the tumor to die from the inside out while sparing healthy tissue.

Today, human cancer patients are actively taking PAC-1 in a Phase I clinical trial.

While the science focuses on compounds and data, the theme focuses on the pet owners themselves. The ACPP theme covers the cost of the experimental treatments, providing an option for owners who might otherwise face expensive veterinary bills.

Before any pet joins a study, researchers walk owners through the purpose of the trial, the evidence behind the therapy and the limits of the drug’s power. Fan said this honesty allows the team to set realistic expectations and ensures that owners don’t expect a cure.

“We are very careful and very deliberate in outlining to pet owners to be fully ethical that this is an investigational therapy,” Fan said. “We believe that it is safe, we have shown that it works … we just don’t know how well it is going to work, and we tell (pet owners) that.”

Although scientific advancement drives the research, Fan notes that many owners join the trials simply out of altruism. They understand that even if a cure isn’t guaranteed for their pet, their participation could unlock better treatments for future pets and people.

Because pets experience cancer in the same environments humans do, Fan said their findings provide data that is difficult to replicate elsewhere. The team plans to use this specific data to investigate how experimental drugs function across diverse tumor types and disease stages to improve the quality of life in both pets and humans.

“I’m excited about the opportunity to see the maturation of these technologies that can hold promise for people,” Fan said. “It’s all about curiosity, hope and realization that something new and exciting is at our fingertips that could ultimately be impactful to treat humans with cancers that are affecting dogs and cats, too.”