In March 2025, the New York Yankees took the baseball world by storm. The team slugged 15 home runs in its season-opening series. Players using “torpedo” bats — tapered bats with larger-than-normal barrels — accounted for nine of those dingers.

Then, seemingly as quickly as the strangely shaped bats entered the public discourse, they disappeared.

For Professor Emeritus Alan Nathan, who has spent decades researching the physics of baseball, his fascination with the bats was just beginning.

“There was a lot of stuff written about this in the first two, three weeks of the season, and then the interest died out, but not my interest,” Nathan said. “My interest revved up, and myself and (my) collaborators, we talked together about what we might be able to do.”

Nathan’s collaborators on torpedo bat research are Penn State professor Daniel Russell and Washington State professor Lloyd Smith.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The trio has worked together on several projects over the course of more than two decades. Now, they’re working together again to test torpedo bat performance against “normal” bat performance.

“We call ourselves the ‘Three Amigos,’” Smith said. “(Nathan’s) expertise is really the theory of how the test works. I’m the experimentalist, and (Russell) is a different experimentalist.”

Nathan’s work is purely computational, running simulations and dictating what Russell and Smith should test in their labs.

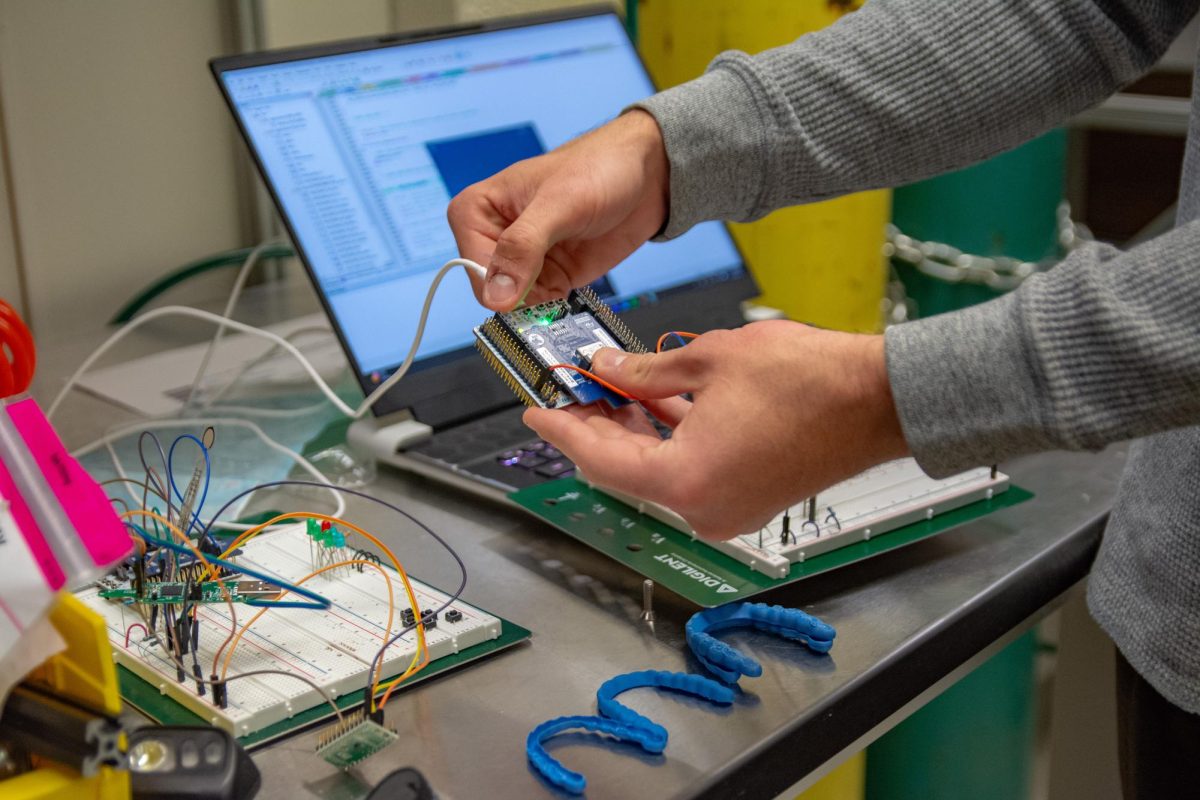

Smith and his team fire baseballs at stationary bats and measure what happens to both the ball and bat after contact using a litany of sensors.

Russell’s work is also lab-based, but he studies the bats’ vibrations using modal analysis.

“I feel like (Nathan) is the brains of the operation, and I’m the brawn,” Smith said. “He identified most of the important things that were needed to test the bat correctly, and then I had the experimentation.”

Torpedo bats didn’t come out of left field, but they hadn’t had their time in the spotlight until this season. Some hitters used the bats at times during the previous two seasons to almost no fanfare.

Nathan pointed to a few advantages of torpedo bats that were apparent even before testing. By moving mass closer to the batter’s hands, the bat has a lower swing weight, making it feel lighter when swung.

The taper also increases the size of the “sweet spot” — the ideal location for a bat to make contact with a pitch — and brings it closer to the batter’s hands.

“If you’re a kind of batter who likes to hit the ball on the inside, this would definitely benefit you,” Nathan said.

After months of simulations and tests, the group’s work is nearing an end. While they’re still working on putting together the final results, both Smith and Nathan said the bats appear to perform as expected.

Torpedo bats deliver similar results to non-tapered bats, albeit with a different sweet spot. They’re not “Wonderboy,” but the bats can prove beneficial to certain hitters.

A few batters across the league swapped out their traditional lumber for torpedo bats last season, but an overwhelming majority stuck with traditional clubs.

Nathan speculates that, after hitters take the offseason to experiment with torpedo bats, many more could be using them in games come this spring.

Next up for the research group is to present their findings at the biennial International Sports Engineering Association conference, held at Washington State this year.

No matter what happens as the team draws its conclusions and as hitters decide what bat is right for them, Smith says it’s nice to see a renewed public interest in a centuries-old tool.

“It was just fun and exciting that there was interest in the wood bat,” Smith said. “There hasn’t been interest in wood bats in a long, long time. So for people to be asking fresh questions, I think that’s really great, and I think it’s going to contribute to the sport.”