Soon, you won’t be able to lie to your dentist about wearing your retainer. A research group at the University is currently developing a smart retainer that will track wear and grinding on teeth.

The smart retainer will use sensors to track data, like a force sensor that tracks grind by detecting when a bite is made. In addition, it will have a temperature control, which determines if the patient is wearing it or not.

Dr. Phimon Atsawasuwan, professor of orthodontics at the University of Illinois Chicago, first came up with the idea for a smart retainer.

Atsawasuwan shared there is no evidence on whether patients are wearing their retainers, because, in rare cases, teeth can still shift. With this smart retainer, however, dentists will have evidence on whether the patient is wearing it or not.

“Most of the time, you have to ask the patient to wear the retainer because, if the patient does not wear the retainer, the teeth relapse, so that’s a major problem,” Atsawasuwan said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

He then reached out to Yang Zhao, professor in Engineering at the University, to help him develop the retainer. Zhao leads the Bionanophotonics Lab, which focuses on wearable metasurfaces, a surface that allows for the manipulation of electromagnetic waves.

After connecting with Atsawasuwan, Zhao organized a research group at the University to work on the retainer, led by Xiaodong Ye, graduate student studying electrical and computer engineering.

According to Ye, the collaboration between the two universities is essential to developing this retainer.

“I think that dentists actually need this device to work on their patients, and our labs have this facility and this target scale to develop such a kind of work,” Ye said.

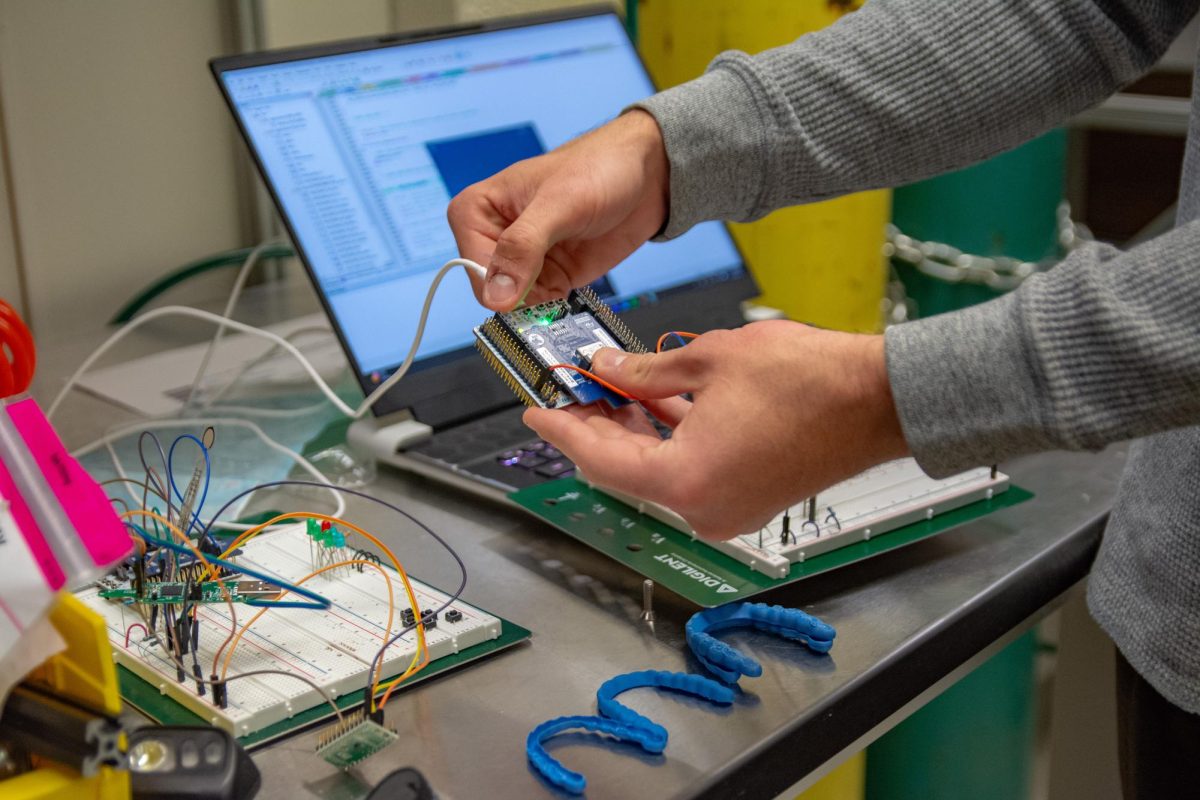

The retainer will keep its standard design but will be sealed in polydimethylsiloxane, a silicone polymer, to keep it waterproof and durable. Additionally, the smart retainer will be controlled with a printed circuit board.

The PCB will have many different parts. In addition to the force and temperature sensor, it will also have a microcontroller and potentially an accelerometer.

The force sensor’s goal is to track the resistance of a patient’s bite. This will allow dentists to track their patients’ grinding for correction.

Oscar Kaplon, senior in Engineering, and Kevin Zhang, sophomore in Engineering, are two undergraduates in the research group currently working to develop their own force sensor.

Each is researching a unique type of sensor for use in the retainer.

Kaplon is focusing his research on a resistance-based sensor, commonly known as a piezoelectric sensor. The sensor has a top and bottom metal plate with a middle medium.

“It’s like a sandwich,” Ye wrote in an email to The Daily Illini. “When you squeeze it, the top and bottom plates have more area contacting. Then, (there is) more area for the current to pass through, and the resistance becomes smaller.”

The current passing through the area allows the retainer to measure the resistance. This allows the sensor to determine the voltage, and, finally, it can correlate that to the force of one’s bite.

However, the group is still unsure what material is best to make the middle of the sensor out of. The medium needs to be malleable enough so that the top and bottom plates can connect. In addition, many materials that are plausible are too toxic for the human body.

“I spend a lot of my time researching different kinds of materials that play possible mixed with carbon black or carbon black on its own,” Kaplon said. “Currently, I’m studying a little bit more on graphene specifically … because that seems conductive enough for it to be applied and used as a force sensor.”

Currently, graphene is the most promising material for the group to use, but Kaplon hopes to keep researching to find a material safer for human use.

Meanwhile, Zhang is researching a capacitance-based sensor. This sensor has easier-to-find materials than Kaplon’s, but it is also much more difficult to measure grind.

The capacitance-based sensor is structured very similarly to Kaplon’s sensor. The medium in this sensor is firm yet flexible and is called a dielectric.

However, in this sensor, the top and the bottom plate never make contact. Instead, Zhang explains, charges move between the plates depending on how close together they are. This rate can then be used to determine the force of a bite.

Currently, that capacitance value is very small, which makes measuring capacitance very challenging.

“So, from a research standpoint and designing, we want to figure out how to increase the capacity so that we can actually measure it for a force sensor, but also keep it within the size constraints of not being too thick,” Zhang said.

Kaplon and Zhang are using previous literature on similar sensors to learn and develop their own, although it is unclear yet which sensor will best fit the retainer.

The group will also use a commercial temperature sensor in the retainer as further evidence for patient use.

“It’s detecting whether or not the patient is wearing (the retainer),” said Joanna Li, junior in Engineering. “If it’s at room temperature, then you know it’s not on, but the human body temperature is around 90 degrees Fahrenheit, so once it’s worn, (the sensor) will detect that spike in temperature.”

The accelerometer is a bonus feature that tracks how the patient moves around at night. Using different position values, the sensor tracks acceleration and can determine velocity and position. However, the group is still unsure if the accelerometer will be in the final product.

All the sensors then connect to the microcontroller, which is a type of mini computer. This sends the data to the phone to be viewed.

The group has established a Bluetooth connection between the microcontroller and phone, but the data is coming in too rapidly and continuously.

“So currently, I’m working on being able to slow down the rate of transmissions, so that we only want to collect data once every minute or once every couple of seconds, and that we don’t overload the storage,” Li said.

The other issue Li is working on fixing right now is getting the microcontroller to store the values more efficiently.

The data is transmitted to the phone once the retainer is in the case and charges. However, it is extremely power-heavy to continuously transmit data.

“It’s probably going to be a couple hundred kilobytes of data at once,” Li said. “So the memory needs to be able to handle that, and it also needs to be able to read it correctly without the data getting overwritten or corrupted.”

The last aspect of the smart retainer is the case, which will have a metasurface on it for more efficient charging.

“It’s used to focus or manipulate the magnetic field generated by the retainer case and then focus the energy to the retainer,” Ye said. “It acts like a relay between the transmitter and the retainer.”

The group still has much more research to do on this retainer, and they are excited to continue to develop it.

Kaplon and Zhang’s next step is to design a small PCB that will fit in a retainer, as, currently, the commercial one the group is using is too big.

Li will also work to develop an app, which will display the data the retainer collects. The app can be used by both patients and their dentists.

Li is optimistic about the lab’s ability to continue to develop the retainer and its future in commercial opportunities.

“We’re just hoping this is a design that’ll eventually be able to secure a patent and then be able to be more widely used, because I think it would be very helpful and (help) dentists treat patients’ grinding,” Li said.