Man of Steel: Gymnast redefined after injury

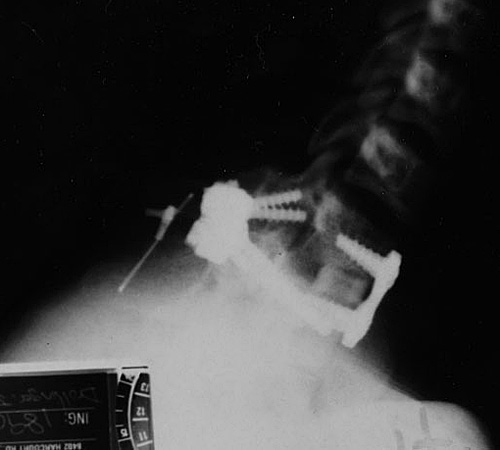

Following a surgical procedure to repair a subluxation of the C7-T1 vertebrae, senior gymnast Jon Drollinger had 10 screws, two plates and two rods placed in his neck to repair damage, as seen in the above X-ray from Oct. 2003. Photo courtesy of Jon Drollinger

Apr 17, 2008

“I can’t believe you just walked in here,” the doctor told him. “You should be paralyzed or dead.”

The “him” is Jon Drollinger.

The grave conversation took place in October 2003 when a Carle Clinic orthopedist discovered Drollinger had subluxation/dislocation of the C7-T1 vertebrae and a herniated disk.

To say this was a surprise to Drollinger would be an understatement, at the very least. He was months away from graduating early from Hoopeston Area High School, traveling roughly 50 miles southwest and enrolling at the University to get a head start.

Instead, he was having his head, neck and spine examined and was told that he should not be alive.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Bad break

On August 13, 2003, Drollinger was heading to practice at the Champaign County YMCA as usual. He was practicing release moves, in this case a Yamawaki, on the high bar and decided to take one more turn on the apparatus before the end of the day,

“It was my last turn up, and I was going to do a release move, it was going to be my last one,” Drollinger said. “I jumped up and started doing it, and I did the tap (a technique used to manipulate the bar to slingshot the gymnast) for it.”

Drollinger recounts what he can remember in surprising detail, standing up from his chair, reliving the moment with body movement and using props to illustrate.

“When I came through the bottom, I was in an arched position, which was normal,” he said. “But I think I arched too early and pulled my body away from the bar. My hands were probably tired or something, and the (rotation) just ripped me off the bar.”

Drollinger’s mishap resulted in a front flip from the bar, and his head was the first thing to land. Though he was practicing in a foam pit to help prevent bad accidents from occurring, his momentum carried him beyond the safety of the pit and towards the concrete floor.

“He came through the bottom and did a flip and landed horribly, horribly wrong,” Drollinger’s then-coach Kurt Hettinger said.

Separating him from the concrete floor was two inches of padding – hardly enough to stop Drollinger’s violent release from ending well.

Drollinger was lucky the accident happened when it did – the pad that barely cushioned his fall used to not be there at all. Its timely placement may have saved him from a skull fracture.

“I remember the force, the impact,” he said, “I’d never hit anything harder.”

Understandably, Drollinger’s memory of the events that followed is a little hazy.

“You could compare it to being knocked out I suppose,” Hettinger said. “He was certainly loopy, I mean you could have a conversation with him, but if you asked him simple questions like what was his parents’ phone number, he wouldn’t remember.”

“I was really out of it, the ambulance came and I was passing out,” Drollinger said.

Conflicting opinions

Drollinger was immediately taken to the hospital for preliminary X-rays, where it was determined that everything looked fine.

“He didn’t have any pain in his neck or anything, so they told him to take some days off, gave him some pain medication and that was about it,” Drollinger’s father, Mike, said.

Doctors dismissed the possibility of initial damage because of Drollinger’s strength in his neck.

“My neck felt completely fine, I was working out, the only problem was that I had pain in my triceps, up in my armpit almost,” Drollinger recounted. “I had numbness in my fingers, too. It was really strong at the beginning, and then it started to fade after about a month and a half, but it was still there. I always had this weakness in my hand.”

Upon returning to the gym, Drollinger tried to resume as much of his old routine as he could. Figuring that if the doctors couldn’t find anything, then he could will himself back into the sport and resume training. But try as he might, Drollinger soon found that the pain in his triceps wasn’t dissipating, and he soon discovered a new limitation.

“The weakness in my right hand was unbelievable, I couldn’t hang onto a bar,” he said.

Drollinger went to his family physician, which yielded nothing, then to a nerve specialist who told him that he had either carpel tunnel syndrome or tennis elbow. Another round of tests found that he may have a torn rotator cuff. Throughout all the testing, prodding and diagnoses, Drollinger had a hard time believing any were getting to the root of the problem.

“I was like, how did that just happen, any of those happening right after this accident? It just doesn’t seem logical,” he said. “I don’t know if I was getting frustrated because I started working out and wasn’t doing well or what. But it was just strange because I couldn’t hold on to the bar. Finally, it got to the point when we went back to the (Carle) clinic again.”

It was then that Drollinger was X-rayed once more by an orthopedist, and the subluxation and herniated disk were found. The vertebrae were dislocated and pinching nerves causing Drollinger’s arm numbness, pain, weakness and the like.

It was then he was told that he was lucky to be breathing and that surgery was needed to repair the damage. Jon’s father assessed the situation and quickly came to find the family HMO would not cover the surgery – at least not in Champaign.

“I called USA Gymnastics, and one of the guys there referred me to the head of surgery at St. Vincent (in Indianapolis),” Mike said. “We went in and saw the neurosurgeon, Dr. Karahalios, who walked in after seeing Jon’s charts and said, ‘You just don’t see people walk in here with this kind of injury.'”

Karahalios presented Drollinger with options, but only one that would allow Drollinger to partake in gymnastics.

If the two vertebrae could be fused back together through surgery, and no further complications arose, like bone removal, Drollinger would have the option of competing again. This procedure, of course, was the most dangerous option.

Given that the possible outcomes weren’t too favorable, Drollinger was, understandably, slightly torn as to what to do.

“(Dr. Karahalios) told me what happened and left the room. I started talking about it with my parents, and I kind of broke down right then.”

The normally staunchly strong Drollinger is gone now. His stout demeanor has been replaced by one that is more exposed and aware of what might have been.

“Just the possibility of something going wrong, because they’re operating around your spinal cord. Anything could have happened.”

He pauses, collecting his thoughts.

“The possibility of me waking up from surgery and only being able to use my left arm … both of my legs and my right arm could have been paralyzed, and it was something I had to deal with.”

But after showing a more vulnerable side, he quickly reverts back to a tenacious mindset.

“So that was tough.”

Surging ahead

So, on Oct. 30, 2003, at 7:59 a.m., Dr. Karahalios started to operate on Drollinger.

Placed on the surgical table facing the ceiling, there was an incision made along the right side of his neck. According to the medical report from the surgery, the herniated disk was mobilized and removed, the incision was sealed and Drollinger was rotated onto his stomach.

“The disk was scraped out in that first part,” Drollinger said, putting it bluntly.

Now facing the floor, another incision was made on the back of his neck. Scar tissue was removed from the vertebrae. After placing the initial set of surgical screws and rods, Drollinger was flipped once more and again had metal installed in his neck.

All together, he now had 10 screws, two plates and two rods in place to reset the damage from the high bar fall.

“We never knew for eight hours that they didn’t have to take any bone at all until they came out and told us,” Mike said. “For those eight hours, we just sat there in the waiting room, just sat there the whole time, every hour or two someone would come out and give us a report.”

The risky, complicated and beneficial surgery was amazingly achieved.

A piece of cadaver bone was placed to help with the fusing, and Drollinger’s body was completely sealed.

After being relegated to a bed for a day following the successful surgery, Drollinger walked the next day. The day after that, he climbed stairs, and the following day he was given an Aspen Surgical Collar to wear and was sent on his way.

Once at home, however, Drollinger realized he wouldn’t be sleeping on a flat surface any time soon with his new neck brace. His new bed was an arm chair, one that he would get to know well.

“I had to sleep in that recliner for about a month,” he said. “So that sucked. That was horrible.”