Column | After years of stagnation, NCAA needs fresh leadership

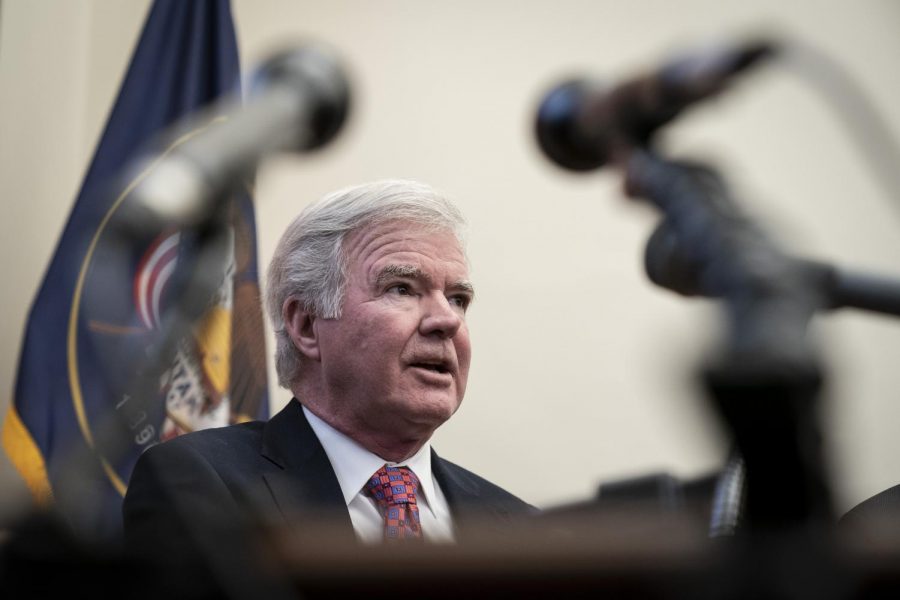

Photo Courtesy of Drew Angerer/Getty IMAGES/TNS

NCAA President Mark Emmert, speaks out against anti-transgender legislation at a brief press availability on Capitol Hill on Dec 17, 2019. Emmert’s lackluster initiative in the past ten years demonstrates a need for new leadership, Claire O’Brien writes.

Apr 15, 2021

Mark Emmert’s NCAA presidency has been a trainwreck. And it’s never been more evident than right now.

Emmert has been the NCAA’s president since 2010. He’s been dunked on several times for his lackluster leadership, including during a 2014 #AskEmmert Q&A.

Lately, though, Emmert hasn’t done himself any favors. The status quo largely remains; it is just now athletes’ diets aren’t micromanaged following a 2014 rule change that allows athletes unlimited meals and snacks.

From refusing to invest in women’s sports to refusing to compensate athletes, the NCAA looks like Ebenezer Scrooge. And that’s under Emmert’s watch.

Emmert seems to think the NCAA needs to pick and choose where to allot money, as he chooses to splurge on the annual men’s basketball championships yet won’t pay the student-athletes who compete at that competition. In early 2020, the NCAA lobbied against legislation in Congress that aimed to pay student-athletes. Emmert is fighting a losing battle and only looks more out of touch when you consider he takes home a 7-figure salary.

But states are taking action to enact change. California, which is often a catalyst when it comes to passing progressive policies, passed legislation in 2019 that would allow athletes to make money from endorsement deals.

While California’s law doesn’t go into effect until 2023, the courts may force the NCAA’s hand sooner. The U.S. Supreme Court is currently reviewing NCAA v. Alston, which addresses the issue of compensating student athletes.

The NCAA is essentially the only business in its market. If athletes want to play at a highly visible level in college sports, they essentially have to play at a Division I school.

And the NCAA’s monopoly status has been litigated before. In 1984, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the NCAA’s TV plan violated U.S. antitrust law.

The NCAA continues to fight tooth and nail to not compensate athletes. Here’s a direct quote from its Alston brief: “Athletics contributes to the overall college experience, plays a lasting role for alumni, provides playing opportunities to the nearly half-million young men and women who compete annually and helps many student-athletes obtain a college education, which carries substantial long-term benefits.”

Sure, all those things are true. But what the NCAA leaves out is that many aspects of student-athletes’ lives are micromanaged. For instance, student-athletes have to run summer employment (or employment in general) by the compliance office to make sure they don’t violate student-athlete amateur rules.

The winds of change are blowing in Emmert’s face, and though he seems to slightly concede this reality, he’s more enthusiastic about getting windburned.

The NCAA likes to act like it can’t pay student-athletes, but it isn’t destitute. As a nonprofit organization, it does not have to pay taxes, so taxpayers pick up the slack. The NCAA had $480,000 to spend on lobbying Congress against the idea of paying its athletes, among other issues, last year. It had a net profit of $24.7 million in fiscal year 2017, according to its tax documents.

Its member schools are not hurting for cash either. To use a local example, Illinois’ athletics department made a net profit of $927,894 last year alone. If, for instance, the University were to compensate each of its roughly 530 student-athletes $15 per hour, which will be the minimum wage in Illinois in 2025, for 25 hours of sports activities per week for 20 weeks out of the year, it would cost $3.975 million.

Critics could argue that figure is roughly four times the net profit and thus athletes should remain uncompensated.

But lack of finances is no excuse. The athletics department can gather more donations or lobby lawmakers to help cover the cost. It is more than capable of finding other sources of funding.

All these groups are nonprofits, making them tax-exempt, so the profits they generate are merely profits. Yet when it comes to giving some of that wealth back to the people who generate it, the NCAA suddenly has empty pockets.

Emmert’s organization is also pretty stingy when it comes to equal investment and living up to Title IX, with its extraordinary underinvestment in women’s sports on full display.

The NCAA’s refusal to invest in women’s sports has never been more visible, and Emmert isn’t taking concrete steps to make equality a reality.

The NCAA women’s basketball tournament had half the budget of the men’s basketball tournament, and weeks after that came to light, the NCAA seemed to take a slight baby step toward getting the message.

Journalist Emily Ehman, who played volleyball at Northwestern and is now a Big Ten Network analyst, tweeted April 8 that commentators would not be provided for the first two rounds of the NCAA women’s volleyball tournament.

One day later, after Ehman’s tweet went viral, ESPN announced commentators would be provided at every match. But the fact it took the internet to speak up and point that out shows that while the winds of change are sweeping the land, it’s merely a gentle breeze for the NCAA.

The NCAA looks progressively archaic with this weak support of women’s sports. And it’s refusing to listen. Female athletes weren’t invited to Emmert’s table a couple weeks ago to air valid concerns about gender inequality and the NCAA’s refusal to pay athletes, among other issues.

Emmert launched a commission to investigate gender inequality, but the issue at hand is painfully obvious, its resolution is equally as obvious and the “review” seems to be a mere technicality, like it’s just something to check off a box.

Emmert has embarked on a low-effort apology tour designed to put a Band-Aid on valid concerns and criticisms. As I wrote last week, he isn’t interested in championing women, non-binary and transgender people in sports, and the NCAA would be better served by better leadership.

While Emmert has never been a strong, vocal supporter of social justice causes, his lack of a moral compass continues to be mind-boggling.

To his credit, Emmert has shown moderate interest in pushing against discriminatory laws in the past.

Emmert’s organization took a stand for LGBTQ+ rights in the past, pressuring states such as Indiana and North Carolina to reverse anti-LGBTQ+ laws.

The NCAA pulled championships out of North Carolina following the state’s passage of a bill that discriminated against transgender people in 2016. North Carolina voters ousted the governor who signed that bill in the 2016 election, and the law was repealed the following year.

When the NCAA applies a full-court press on these states, they often change course. Now, as a number of states propose legislation to try to restrict transgender athletes’ ability to participate in athletics, the NCAA isn’t actively fighting the bills, instead opting to sit on the bench, completely disinterested in what’s going on outside of sports.

Mississippi passed a law in March, signed by Gov. Tate Reeves March 11, restricting transgender athletes’ participation in sports. It wasn’t for a month, until April 12, that the NCAA finally made a comment about the legislation, saying it might pull championships out of Mississippi.

This silence breaks the NCAA’s own precedent. It didn’t hesitate to pull events from North Carolina after that state’s law passed, but as these anti-LGBTQ+ bills pile up in state legislatures, the NCAA isn’t pressuring them to kill the legislation.

When the NCAA’s home state of Indiana passed a law in 2015 critics said would allow businesses to discriminate against the LGBTQ+ community, Emmert said his organization opposed discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and expression. Indiana reversed course, and then-Gov. Mike Pence was likely to lose re-election in 2016 in the wake of the bill.

But as is so often the case with Emmert, it’s all hot air. Months after Emmert opposed Indiana’s law, he donated $1,000 to Jeb Bush’s 2016 presidential campaign. Bush opposed same-sex marriage during his presidential run and did not agree with Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 Supreme Court decision that legalized same-sex marriage in all 50 states.

As states around the nation try to limit transgender children’s ability to participate in sports, the NCAA hasn’t really defended transgender athletes. Defending the students should be a no-brainer for the NCAA, especially since experts say these laws are not scientifically sound, noting transgender athletes do not have a competitive advantage over cisgender athletes.

It’s not like the NCAA taking a stand is always futile. To the contrary, the NCAA has applied pressure on states to be inclusive and work for all its citizens.

The NCAA made a big show of equality and social justice initiatives last year and got people to show up to the polls, but now it isn’t keeping up the energy. As states pass laws that make it harder for people to vote, disproportionately Black and lower-income voters, the NCAA has not taken a stance against the discriminatory voting laws.

Major League Baseball has been more vocal about these laws than the NCAA. April 2, after the Georgia legislature passed and Gov. Kemp signed the bill, MLB moved its All-Star Game out of Georgia. The NCAA has been silent on the issue.

From failing to compensate athletes to not taking a strong stance for inclusivity for all, the NCAA has largely upheld the status quo in society under Emmert’s watch.

The NCAA has a history of standing up for marginalized communities. Now, Emmert is silent, and the NCAA seems to have changed course. What’s the matter with Emmert?

@obrien_clairee

[email protected]