Keeping the memories alive: The 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

Apr 21, 2015

They found her in the middle of the Syrian Desert.

She was 2 years old, lying abandoned on the side of the road, when a group of French nuns first approached her. They were there to save other stranded children just like her, hoping to bring them back to French orphanages for safety. Without a family or a home, the girl had nothing left to do. She had to go.

How did she get here? It was a question the girl often wondered.

She knew a series of abnormal roundups first began in Constantinople on April 24, 1915, when the Ottoman Empire jailed, tortured and killed politicians, teachers, writers and clergy. The men came next; they were tied together with ropes, then shot or stabbed near the countryside. The girl was in the next group, with other women, children and the elderly. They were told to pack lightly and be ready to leave and that they would be taken to safety. Instead, they led them to this desert.

But there was an even more important question: Why was she here?

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Several years later, after analysts and historians looked at the historic event, she finally knew.

Because she was Armenian.

***

Ashley Megurdichian will always remember the story of her great grandmother, Attia, who survived what is today known as the Armenian Genocide.

Her great grandmother’s story contains tragedy and pain but inspires her to make a difference. It has empowered her to become the president of the University’s Armenian Student Association and urged her to document her ancestors’ and relatives’ past.

“I think it is important to spread awareness so that massacres like this do not happen again,” Megurdichian said. “Not many people are aware that the Armenian Genocide happened.”

Megurdichian, however, will be able to further this goal throughout the week, as her organization will sponsor a series of commemorative events, in works with the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide and Memory Studies and the Future of Trauma and Memory Studies Reading Group.

The first commemorative event will be a reading of Armenian literature in various languages and proses Tuesday at 6 p.m.

Helen Makhdoumian, graduate student in English and the event’s primary organizer, said the event is meant to keep the culture alive. She said the memories of the victims carry on through literature better than a textbook or lecture.

“History books cannot give a perspective of the individual and everyday experiences,” Makhdoumian said. “For some Armenian writers, literature is a way to honor their elders’ wishes about telling the story. … Literature becomes a medium through which individuals can speak through the silences and meditate on these memories of trauma.”

To Makhdoumian, keeping the memories of the Armenians alive means surviving her grandparents’ stories as well.

Makhdoumian’s grandfather, Krikor, was a child when the uprooting first began. He lost his family and his brother during the relocations. Krikor was rescued by a local Kurdish shepherd; he was stripped of his identity and name but left him with a tattoo, so he would not forget his true heritage, as both a Christian and an Armenian. The shepherd protected Krikor for four years, forcing him to hide in the hay when danger was near.

But even though these memories were painful for her relatives to remember, Makhdoumian knows they have to be heard.

“Many survivors tasked their children and descendants with stories to keep the memories alive and make their stories heard. I think many feared that the world would forget,” Makhdoumian said.

A 2006 documentary by filmmaker Andrew Goldberg will be screened Friday, the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, at 5 p.m., and is sponsored by The Future of Trauma and Memory Studies.

Jessica Young, graduate student in English, is the key organizer behind the documentary showing.

“Trauma issues of genocide are a difficult subject,” Young said. “Not everyone wants to study them or think about them, but it is necessary to learn about the politics involved, read about them and make sure that victims of genocide memories are not lost. We are hoping that our film can raise that part of awareness.”

Makhdoumian’s passion inspired Young to begin working with the commemorative events of the Armenian Genocide. But Young has always known the tragedies of Genocide. Her grandparents were German Jews, and in the 1930s, they fled their home country to the United States to escape the impending danger and violence.

“I grew up listening to stories about my family who perished in the Holocaust,” Young said. “I have grown up with that, and it has made me sensitive to other issues against police, genocide and trauma. It was always in the background. They had to fill in the gaps about what happened to their friends, that they died in a concentration camp or on their way. When you go through that, there was a lot of fear. It was not something that they often talked about.”

Young said she believes these commemorative events prevent the perpetrators from winning.

“If you forget them, the perpetrators win,” Young said. “You have to commemorate. Without that, it obliterates people, their culture, their history – and that is what genocide is. You have to fight against genocide. The sole survivors — remembering and learning about them — is important to fight against the violence.”

***

Though the events of the Armenian Genocide occurred 100 years ago, the world is still feeling its affects.

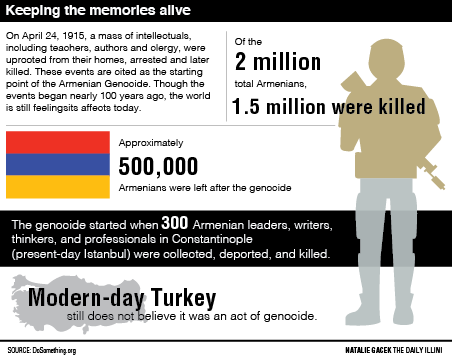

Nearly 1.5 million Armenians died after the events. The remaining 500,000 survivors were scattered across the globe. The Ottoman Empire kept the acts a secret, as the only primary artifacts and studies come from first-hand witnesses and journalists on the scene.

In the aftermath, however, Turkey prohibits any conversation about this event in its history. They believe the events were not act of genocide.

Peter Fritzsche, University professor in history specializing in topics about holocausts and genocide , said this is preventing the world from making a difference and moving on.

“Genocides are now remembered by each other,” he said. “People as nations remember the sorrows and victimization. … What is unproductive is for Turkey to say, ‘It was not genocide, and you insult our nation if you refer to it as genocide.’ It is not the requirement to call it a genocide; the requirement is to discuss it, to put the issue on the table and to explore it. If it is a slap in the face, that is good. At least we are bringing the discussion to the table.”

To Megurdichian, the events on campus are the next step to fighting Turkey’s refusal. It is a way of surviving her grandmother’s stories and making sure her pain was worthwhile.

“I hope that people will learn about our history and who we are as a people,” Megurdichian said. “But most importantly, I hope that they learn about this genocide, so that even if the government cannot officially recognize it, they will still know the truth.”