Billionaire says anyone can repeat his success

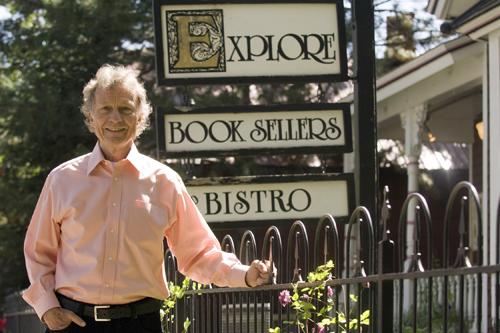

In this Sept. 2, 2008 file photo Sam Wyly poses in front of his Explore book store in Aspen, Colo. Wyly went from growing up in a house without electricity to amassing a fortune estimated at $1.2 billion. Ed Kosmicki, The Associated Press

October 1, 2008

DALLAS – Sam Wyly went from growing up in a house without electricity to amassing a fortune estimated at $1.2 billion, and he says anyone can follow in his footsteps if they work hard enough and watch for opportunities.

Wyly built and sold software companies, rescued a steak house chain and revived an arts-and-crafts retailer.

Now, he’s in the green-energy and hedge fund businesses, although he gets more attention for his political activities. He has given generously to Republican causes and candidates, including the Swift Boat campaign that helped re-elect President George W. Bush in 2004 by tarring his Democratic opponent.

Wyly, who turns 74 next month, just published a memoir, “Entrepreneur to Billionaire: 1,000 Dollars & an Idea.” It’s an American archetype: the rags-to-riches story, with plenty of references to football, farming, hard work and small-town sensibilities.

It’s not a how-to book, and it’s not one of those inspirational tomes that fill bookstore shelves, even though he says he wrote it to help and inspire others.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Instead, it’s a chronological retelling of lessons learned, challenges accepted – and usually overcome, deals made and money amassed, all told in a writing style that is simple, straightforward and not inward-gazing.

Wyly grew up Lake Providence, La., where his father was a cotton farmer. One spring, he decided against the safe move of selling his crop long before harvest for a set price, and gambled instead that prices would rise by fall. The crop was a bust, and to keep their land, the Wylys were forced to move into a house outside town that had no running water or electricity. Young Sam absorbed a powerful lesson:

“If we had hedged the entire crop, we never would have had to leave Lake Providence,” he wrote.

After high school, where Wyly was an undersized nose tackle on the state championship football team, and graduation from Louisiana Tech, Wyly wound up in Dallas as an IBM trainee alongside a skinny kid from east Texas named Ross Perot.

It was the dawn of the computer age. And Wyly, like Perot, saw an opportunity to sell computing services to companies that couldn’t afford to own one of the hulking mainframe machines of the day. Overcoming rejections from bankers, Wyly found funding – he had only $1,000 himself – and started University Computing, which he took public in 1965.

From there, Wyly, sometimes acting with his brother, bought and sold several companies including a mining outfit, Bonanza Steakhouse and the arts-and-crafts chain Michael’s Stores Inc., which sold to private equity groups in 2006 for $6 billion.

Wyly also took on AT&T;’s monopoly in data transmission. And he built Sterling Software then sold it to Computer Associates for $4 billion, only to launch a proxy fight against the new owners, which he settled for a payment of $10 million.

The hedge fund he co-founded, Maverick Capital, manages about $10 billion in assets. The man who once diversified his holdings by buying an oil refinery is now excited about renewable energy; he’s the largest shareholder of Green Mountain Energy.

In March, Forbes magazine estimated Wyly’s net worth at $1.2 billion, putting him among the richest 1,000 people on the planet.

Wyly said anyone with an entrepreneurial streak can do what he did.

“I think there is just as good opportunities today as when I started,” he said in an interview. “Some folks give up too soon when they should be persistent and determined and just keep on persevering until they finally make it work.”

There is no mention in the book of a federal investigation into the use of tax shelters by Wyly and his brother, Charles – Wyly declined to comment on the issue. And there is only scant mention of politics, although the Wylys have told interviewers they’ve given about $10 million to Republican candidates and causes since the 1970s.

Notably, Wyly gave $2.5 million to a group that favored Bush over John McCain in the 2000 Republican primaries. Four years later, he donated $20,000 to the Swift Boat campaign that raised questions about Sen. John Kerry’s military record in Vietnam, helping scuttle Kerry’s challenge to Bush.

In an interview, Wyly said he is neither leaning toward McCain nor Democrat Barack Obama this year, and won’t get involved in the race.

“The last couple of years, we (he and Charles) basically haven’t made any political contributions to anybody and really don’t plan to,” Wyly said.

So he won’t finance another Swift Boat-type campaign this time around?

“No, no, no,” Wyly said. Laughing, he added, “I’ve done that, and other people can do that now.”

Wyly acted horrified that although T. Boone Pickens poured far more money into the Swift Boat ads, some news stories highlighted the involvement of the Wyly brothers, who were longtime Bush family friends and “Pioneers,” big-dollar fundraisers for George W. Bush.

“One of the most highly charged topics around is politics, and one that’s more highly charged is political money,” Wyly said. “People just love to write and read about it.”

If so, maybe Sam Wyly has another book in him.