Engineering a solution

February 19, 2009

It’s one class that engineers absolutely have to take to graduate: senior design. Almost every department of engineering has its own specific class where the students form groups and take on a company’s engineering problem.

The goal of the class is to transition students from sitting in class to actually working on real world problems. This way, once seniors graduate, they have had some hands-on experience.

“Once they graduate they will have a tremendous amount of real-world experience so whatever company hires them, they have already done things in the real world so they are much more prepared than the competition,” said Harry Wildblood, coordinator of project design activity.

Seniors have 17 weeks to work on the project, and they must complete it. Each project is specifically chosen so it is within the undergraduate engineer skill range but still a challenge.

Pregis Plant Manager Dennis Hughes has had a positive experience working with the senior design project. The company, based out of Indiana, produces packaging materials and needed a new knife. Hughes was impressed by the seniors and would have hired them, but the group members already had post-graduate plans.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“It’s a win-win for both the students and the company,” Hughes said.

Manure team

Along with all the corn Illinois has to offer is a lot of manure.

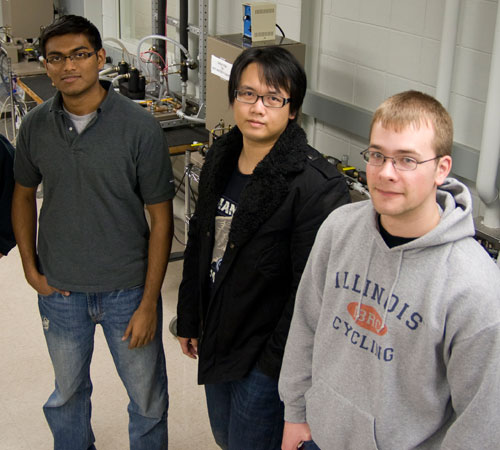

This mechanical engineer design team of Kevin D’Souza, Philip Kwon, Trevor Losch and Ben Slater is working for Walker Process Equipment to build a viscosimeter.

The company needs a viscosimeter to measure the fluidity of their sludge, or manure and water.

Viscosimeters usually cost seven to eight thousand dollars, and aren’t specific to manure. The design team’s task is to build a viscosimeter from scratch, specifically for manure. The end product will look something like a mixer.

The team is working with a $1,000 budget, a number they consider feasible for the task.

The team has to research more about viscosity, learn how to draw on a computer and actually build the viscosimeter.

“It’s our first time building something from scratch. It’s an interesting process about taking an idea to a finished product. Hopefully in a couple of months we will be done and that is quite an accomplishment,” D’Souza said. Because they are designing the viscosimeter and haven’t done tests yet, the manure smell hasn’t gotten to them.

But they expect it probably will, before all is said and done.

Primrose Candy Company

It’s the candy that comes with every check at a restaurant, as a subtle reminder to freshen your breath: a peppermint.

This senior design group, consisting of Donald Darga, Tim Herman, Andrew Kahle and Frank Lam, was assigned to Primrose Candy Company, a company that mainly produces hard candy, including Starlight Mints, Butterscotch Buttons and IBC Root Beer Barrels.

Primrose’s main problem is that they are producing a significant amount of scrap, or candy that cannot be sold for various reasons.

Scrap candy occurs if the swirls in the peppermint go in wrong, if the candy won’t cut right or if candy is burned or falls off the conveyer belt.

Most candy companies have 5 percent scrap, Darga said, though Primrose’s is higher.

By reducing Primrose’s scrap level by 5 percent, the group would save the company around $1 million dollars, Kahle said.

The seniors decided that their main focus would be the candy cooker and the conveyer belt.

The cooker has to be manually checked. Because heating is a very important part in candy making, the temperature has to be set just right or else a whole batch of candy could be ruined.

Although the company is located in Chicago, the design group will visit the plant a couple of times over the semester. They recently toured the plant and took pictures and videos of how the cooker works to get a good idea of how to build their control system.

“There’s definitely a difference between sitting in class and going to the plant, being there and looking at everything,” Darga said. “It’s a little overwhelming.”

Despite the new experience, Darga is confident that they will be able to get the project done and help the company.

“We got back and we started breaking it down step by step, so we know we can do it; it’s just a matter of putting in all the work,” Darga said.