Oldest professors share their campus memories

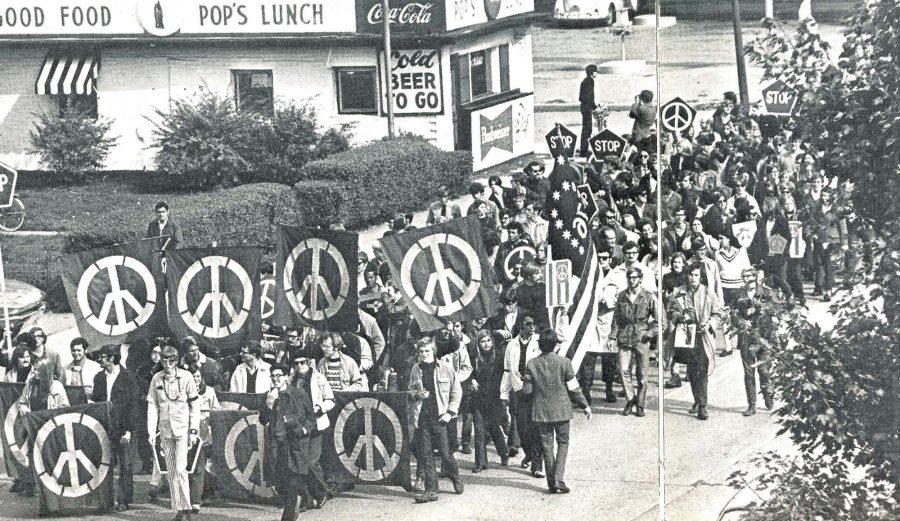

Students protest the Vietnam War with hopes and aspirations for world peace on October 15, 1969.

September 14, 2016

For many students, the University will become a small chapter of their lives after graduation.

But for professors, it represents books — even volumes — of their lifetimes. Three professors who have spent a major portion of their lives on campus offer their perspectives on how the University has changed throughout their time teaching.

Winton Solberg, professor emeritus of history since 1961, witnessed the impending institution of theatrical arts. The Krannert Center for the Performing Arts was formerly a gas station with a few houses behind it.

“It was a totally different development,” Solberg said. “Foellinger was the place where there were the things that you now find in Krannert. Plays were given on the stage of Lincoln Hall. It was just a different world.”

Harold G. Diamond, professor emeritus of mathematics, became a faculty member in 1967 and retired in 2002. He recalled 49 years of campus history from his office in Illini Hall, where he moved after retirement.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Diamond remembers major architectural developments throughout the 1960s, including the construction of the Foreign Languages Building and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Sciences and Technology.

The convenience of full-time advisers was another benefit during the 1960s.

Diamond recalled how faculty members across the board would get a certain number of people who discussed programs with them at certain times of the year.

“They were not all experts in requirements — there was a kind of hit-or-miss enterprise,” Diamond said. “Now full-time advisers pay more attention to (students) and give them higher-quality advice.”

New academic institutions and counsel weren’t the only factors that shaped a student’s education. Historical events triggered various work ethics on campus.

Diamond said technology and faculty members were cultivated quite extensively during his early time at the University because of the launch of the Sputnik in 1957.

“It was really a very good time to be in a technological subject,” Diamond said. “The math expanded, the engineering departments expanded. Scientific developments came in response to where we stood vis-à-vis the Russians.”

In contrast to this time of enlightened curiosity, the Vietnam War cast a different tone on students and faculty. A mass depression spread as students thought about the likelihood of being sent out into the war. Demonstrations on campus called for the end of the war and its threatening draft. For safety purposes, the administration decided to glue down the decorative rocks placed around the campus. Trucks had loads of glue that they poured on top of them so they were immovable.

“It was the opposite of what it was like in the earliest time that I was here,” Diamond said. “People just didn’t have any enthusiasm for school beyond staying out of the draft.”

As a specialist of religion in American culture and the history of the University, Solberg tracked how the education of faith has evolved in a secular institution.

In the early 20th century, the University pioneered allowing Catholic, Protestant and Jewish religious foundations to offer courses. A student could take up to six credit hours if the foundations got properly registered through the state and had decent standards.

“This was the only University in the nation in which this was being done,” Solberg said. “Today, the University does offer courses on religion as the institution interprets the constitution somewhat differently.”

Bruno Nettl, professor emeritus of musicology, has served on the campus for 52 years. He came to campus in 1964, formally retired in 1992 and continued regular part-time teaching until 2005. If Nettl could sum up the evolution of the University in one word, it would be: technology.

“The introduction and development of technology has changed dramatically,” Nettl wrote in an email.

Nettl also sees a decline in “the emphasis on traditional humanistic disciplines.”

“There’s much less interest in taking undergrad courses or majoring in fields such as European languages, history (and) social anthropology than when I came,” he said.