Campus History: University observes Juneteenth for first time

June 19, 2022

On June 19, 1865, Union Army General Gordon Granger informed residents of Galveston, Texas of the emancipation — proclaiming and enforcing the freedom of the enslaved people of Texas, the last in the Nation to receive word of the emancipation.

Although Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation more than two years prior, emancipation was not uniform across the southern states. Geographically isolated enslavers migrated to Texas to escape fighting, and Texas’ slave population increased to over 200,00 by the end of the Civil War.

Instead of using the emancipation proclamation — which made slavery illegal by law but not in practice — Black communities chose to mark the end of their enslavement with the date of Granger’s arrival in Texas, which brought freedom upon the last group of formerly enslaved people. Thus, Juneteenth — a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth,” became a de facto celebration commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans.

156 years later, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law on June 17, 2021, making Juneteenth a federal holiday. This is the first year the University is observing Juneteenth, with eligible staff and faculty receiving paid time off (the University observed the holiday on Friday, June 17, as June 19 fell on a Sunday).

While this is the first year the University is observing Juneteenth, the holiday has been celebrated in Champaign-Urbana since its inception. Furthermore, events in Champaign-Urbana regarding the Black liberation, Black Power and Civil Rights movements have mirrored the historical developments in our country writ large.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

—

While the end of the Civil War marked the end of slavery in the U.S., racism and racial discrimination were far from over. In the South, Jim Crow laws perpetuated violence against Black communities, and segregation was rampant. Champaign-Urbana was no exception. Daily Illini archives note the constant refusal of services from Campustown businesses to Black students. University Housing didn’t house any Black students until 1945.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The University never explicitly refused admission to Black students, but it took 20 years after the University’s founding for the first Black student — Jonathan Rogan — to be admitted. However, public elementary schools in Champaign-Urbana had a more fraught relationship with segregation, with many schools not integrating until after the decision.

As the Civil Rights movement grew throughout the ’50s and ’60s, the University became a battleground for Black students. In the introduction to her book “Black Power on Campus: The University of Illinois, 1965–75,” Joy Williamson writes: “An unwavering belief in the importance of education made schools, including postsecondary institutions, an important battleground for Black liberation efforts. Black students became the battering rams and in many ways the vanguard of the struggle for equal education.”

The Greensboro sit-ins in 1960, held at the Woolworth store in Greensboro, N.C., were a series of nonviolent protests. Black students would peacefully sit at segregated counters at the Woolworth store, which ultimately led to the department store chain removing its segregation policy in the South. Started by four Black students, the size of the protests rapidly increased as they continued. While not the first of its kind, these protests would go on to inspire the larger sit-in movement.

—

On Aug. 28, 1963, the March on Washington was held in an effort to promote civil and economic freedom for the Black community. An estimated 250,000 people attended the March. There were several speakers, including Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. This protest was very successful, playing a large part in the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn. He was fatally shot by James Earl Ray. King’s assassination sent shockwaves throughout the nation, which could be felt on college campuses.

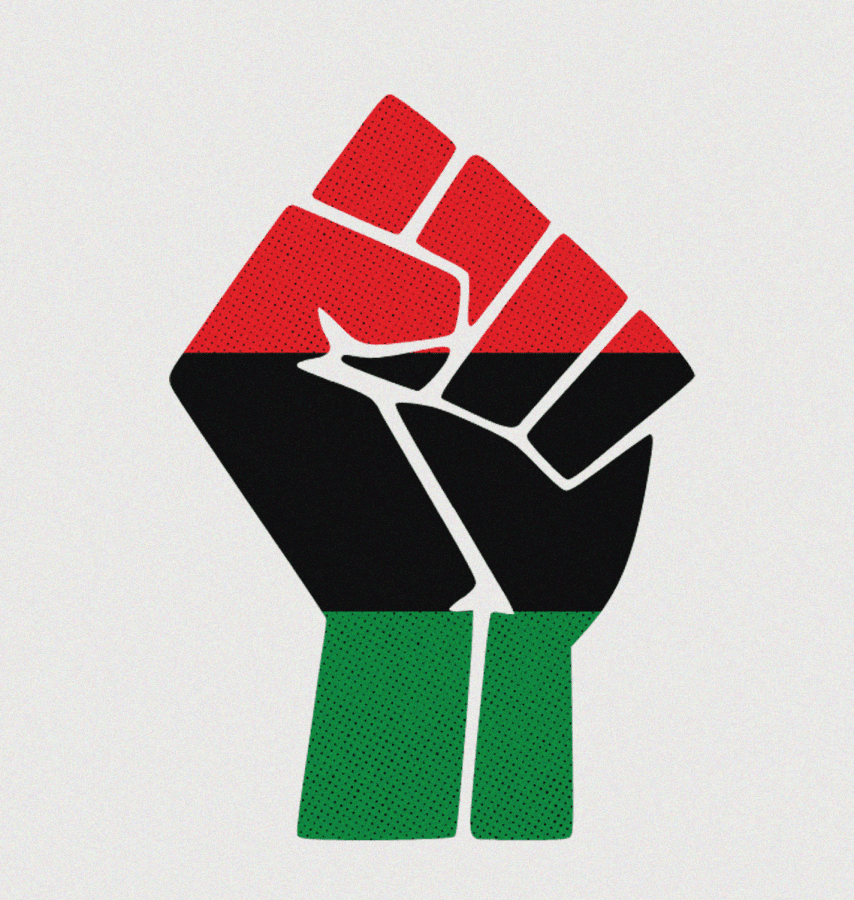

Black Power ideology served as the undercurrent for most campus organizing, especially on the University of Illinois campus. While the Civil Rights movement was marked by nonviolent protest, the Black Power movement, which was influenced by former Nation of Islam spokesman Malcolm X, emphasized a more direct form of action. Still markedly nonviolent, Black Power ideology was more confrontational in its challenges of systemic racism and White supremacy, while, in contrast, the Civil Rights movement leaned into respectability politics.

Black Power ideology played an important role in organizing on campus throughout the 1960s, sparked by the Civil Rights movement and even further empowered after the assassination of Martin Luther King and the rise of the Black Panther Party. Of Black Power ideology’s role in campus organizing, Williams writes: ‘During the Black Power era, Black youths became the ideological leaders of the Black struggle. They helped redefine the goals and tactics of the struggle and demanded change in American institutions, including their college campuses.”

—

While last year, Champaign and Urbana held virtual Juneteenth celebrations, this is the first time since Juneteenth’s inception as a federal holiday that the cities are holding in-person events. Champaign held a Juneteenth celebration at Douglass Park on June 18, and Urbana held a flag-raising ceremony in commemoration of Juneteenth on June 17.