Nikkeijin Illinois Spurlock exhibit to depict the Japanese American experience

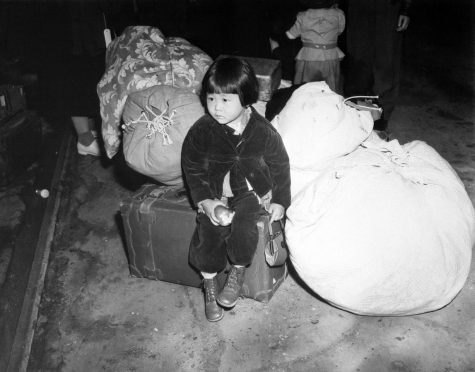

Photo courtesy of the Spurlock Museum

On Sunday, the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures will open a new exhibit, featuring a variety of exhibits related to Nikkeijin.

Feb 17, 2023

In Japanese, there’s a word, Nikkei (日系), for those that emigrate from Japan and settle somewhere else. Jin (人) means person or man.

Nikkeijin (日系人) means a person with Japanese descent who doesn’t reside in Japan. Jason Finkelman, the Nikkeijin Illinois exhibition curator, said the naming of the exhibition was very intentional.

“I wanted to tell the history of the Japanese American experience through the stories of people,” Finkelman said.

The exhibition opens Sunday at noon. There will be a program at 2 p.m. that features panelists including Finkelman, Alice Murata, a professor emeritus at Northeastern Illinois University, and Ross Harano, a civil rights activist and former president of the World Trade Center of Chicago.

Beth Watkins, education and publications manager at Spurlock Museum and project coordinator for Nikkeijin Illinois, said the exhibition looks at the Japanese American experience through the lens of those that are connected to the University in some way.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“There are 12 people profiled in the exhibit,” Watkins said. “They’re all either alumni or staff or faculty of the University. It starts in the 1900s and Jason (Finkelman) is actually the 12th person.”

Finkelman said he’s been working on the exhibit for two years.

“Elizabeth Sutton, the director of Spurlock Museum, and I were in a meeting and we launched into a conversation about some of the research I was doing in my own family’s life in my Japanese American heritage,” Finkelman said.

Finkelman said after that conversation, Sutton contacted him and asked him if he’d be interested in curating a Spurlock exhibit about the Japanese American experience.

“Most of the preliminary research was taking place in the first year,” Finkelman said. “I started looking through a lot more documents and trying to narrow down a small list of potential stories.”

Finkelman said this past summer, he spent a lot of time looking through the University archives. There, he found a correspondence between the University and the University of Minnesota saying the University was reluctant to admit Japanese Americans in 1942.

Finkelman said this letter came in response to Japanese Americans being forcibly removed from the West Coast and looking to get their education inland.

“There’s 110,000 Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from California and the West Coast because it became a military exclusion zone because of the signing of Executive Order 9066,” Finkelman said.

The U.S. National Archives state that Executive Order 9066 was issued by President Franklin Roosevelt in the wake of World War II. Signed on February 19, 1942, the order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to “relocation centers” further inland – resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Finkelman said Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated to 10 incarceration camps spread across the U.S.

The U.S. National archives said relocation centers were situated many miles inland, often in remote and desolate locations. “In the relocation centers (also called ‘internment camps’), four or five families, with their sparse collections of clothing and possessions, shared tar-papered army-style barracks.”

Jennifer Gunji-Ballsrud, Director of Japan House and associate professor of Graphic Design, said her family members had different mindsets towards their pasts.

Gunji-Ballsrud’s father, who is one of the 12 profiles in the exhibition, did not go to an internment camp. Instead, his parents took him back to Japan.

“They were really ostracized there because (Japan) was like ‘oh, you’re a spy, you’re this, you can speak English, we don’t trust you,’” Gunji-Ballsrud said. “(My dad) was made fun of, he was beat up a lot. It was kind of terrible … so they came back to the U.S.

“My grandmother … was very bitter. She would complain about it sometimes,” Gunji-Ballsrud said. “I remember her being kind of an angry woman and kind of angry at both Japan and America for what she went through.”

Gunji-Ballsrud said she and her family try to look at their current life.

“From my perspective and upbringing, we were taught to realize that if we hold onto those kinds of negative things, it’s debilitating,” Gunji-Ballsrud said.

Gunji-Ballsrud’s father came to the University as a student in the 1950s.

“My father loved the University of Illinois,” Gunji-Ballsrud said. “When he came to campus, he felt like this was the best place on Earth … he had an affinity for this country despite the actions of our government.”

Gunji-Ballsrud said that how Japanese Americans feel about the internment camps depends on individual perspective.

Finkelman said he wants to hear from both young and old voices and hear different perspectives and stories, so he created a digital platform to partner with the exhibition.

“I knew that since it was such a limited amount of both space and stories, I wanted to create a platform for more stories,” Finkelman said.

Watkins said the exhibition is relevant to students because the campus has a large Asian and Asian American population.

“This is a significant part of the student body of this university, so even if it is not you, it is your friends, your colleagues, your classmates,” Watkins said. “It’s people that you see and know every day, and this is a part of what affects them and therefore affects all of us.”

Watkins said she hopes students will see the larger historical context within these local stories.

“I think these kinds of stories are always important to look at, again, as we try to grapple with who we are as Americans,” Watkins said.