Study finds climate change correlated to human conflicts

March 1, 2023

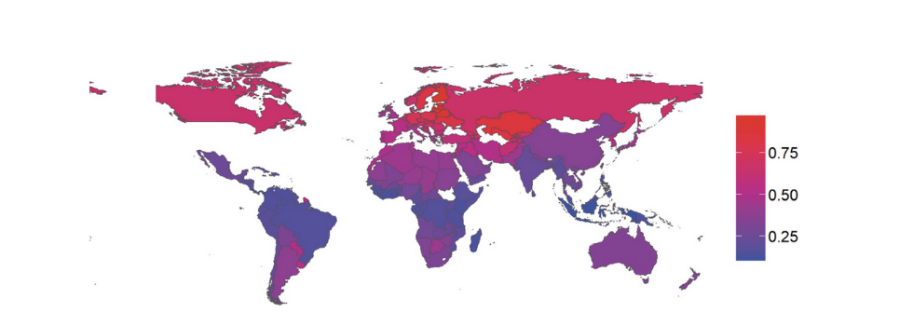

Climate change is everywhere, and how exactly the rise in temperature affects the world has been an international, pressing issue within political spheres. A recent paper co-authored by a UI professor proposes a new framework for exploring the relationship between climate change and social conflict.

The study’s results, co-written by Ujjal Kumar Mukherjee, Snigdhansu Chatterjee and Benjamin E. Bagozzi, suggest “nuanced relationships between temperature deviations and social conflicts.”

Mukherjee is a professor in Business with a joint appointment in the medical school at the University. The study, titled “A Bayesian framework for studying climate anomalies and social conflicts,” is openly available online. Mukherjee explained the thought process behind the study.

“We were talking about the effects of climate change, rising temperatures and the change in the pattern of precipitation, extreme climate events, for example, flooding, tornadoes, hurricanes or drought situations,” Mukherjee said. “How does it affect human life and society, especially when you have a globalized environment where all the supply chain is spread all across the globe?”

From that initial idea, Mukherjee said he and his colleagues began a stream of research to see how climate change might cause human conflict, especially in areas of the world where people are still dependent on agriculture production and raw material production such as coal and mineral mining.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“Whenever you have resource constraints, crime, as well as human conflict, increases,” Mukherjee said. “We try to quantify it at a global scale.”

Mukherjee said that while there have been smaller-scale studies, this study is on a much larger scale.

Chatterjee, a professor at the University of Minnesota, also worked on the paper. Chatterjee, however, warned readers to be wary of results.

“I would be cautious in interpreting the results,” Chatterjee said. “So it says that given the data, this is what we are seeing in the data now. Things change, the climate is obviously changing, and political structures are undergoing changes. These are human beings, and these things keep morphing, and so it’s entirely possible that there may be increased violence, increased conflicts because of climate related issues. Or people may learn to adapt (and) learn to live together with each other.”

Chatterjee said the topic of forced migration plays a part in this discussion.

“Particular villages and community living spaces become unbearable because of temperature or lack of water or something else,” Chatterjee said. “They will be forced to migrate, and given how things are all over the world, where would they migrate to?”

Chatterjee said this is what the three researchers anticipate will be the primary cause of conflict.

Mukherjee added that because of all the variables that contribute to what consists of both climate change and civic, social and other conflicts, the data analysis can get complex. Conclusions cannot be readily made by looking at a single correlation between conflict and temperature.

Chatterjee said this data can be used by two types of people: researchers in the future and political actors.

“We propose this model, and this can be used by future researchers in this area,” Chatterjee said. “So in the long run, nations and governments and policymakers need to be aware of it and need to adopt policies that are more climate conducive, right?”

Both Mukherjee and Chatterjee are continuing their research in this field.

“We would like to involve more climate variables that involve more of a causal structure and then have more precise estimates,” Chatterjee said. “So less uncertainty … a more narrow band of answers, especially as we project things into the future, that will be useful both for us, as well as for policymakers.”