Dating is hard.

Many can agree that navigating the dating scene — especially for broke, preoccupied college students — is challenging. Limited time, competing attentional demands and the quality of one’s dating pool are potential explanations for the stress that comes with the world of dating on a college campus.

These challenges only scratch the surface of what makes dating complicated for some students. Queer college students, and queer folks in general, face a myriad of unique challenges in the dating scene.

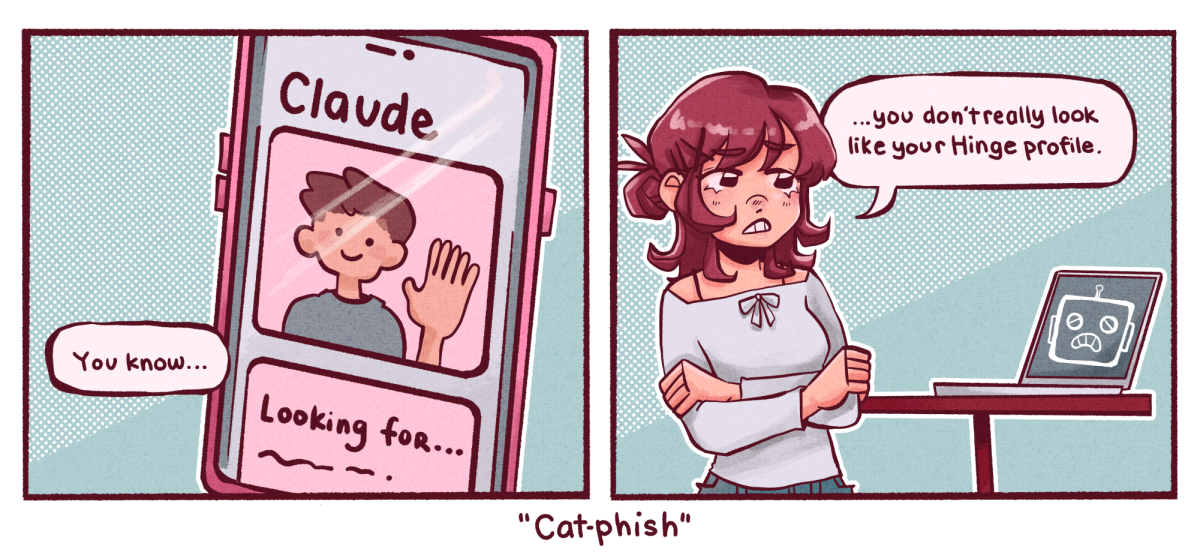

Hookup culture, ‘the apps’

While hookups know no sexuality, they are a hallmark of the LGBTQ+ dating experience.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Many queer students, especially gay men, flock to so-called “hookup apps” like Grindr, Scruff and others, seeking more physical relationships.

University alum Asif Ali, a recent graduate, found navigating hookup culture as a gay man in Champaign-Urbana challenging.

“I will say, sometimes it does feel like everybody is just looking to hook up, and it kind of gets difficult to just date for dating’s sake,” Ali said.

The widespread emphasis on casual sex and the hookup apps that often facilitate it have given rise to problematic behaviors.

“Sometimes dating apps can make it easier to connect, but they also show you the worst side of people,” Ali said. “Sometimes they’re anonymous, and they think that they can get away with saying some really off-handed s— … It’s fine to have your preferences, but it’s not OK to be racist on your profile.”

Ali said that despite his experiences with racism on dating apps, few people subscribe to that culture of bigotry.

“That very small minority is just very loud about it,” Ali said. “I think there are way more chill people than we realize. And to be fair, they’re not going to be on Grindr because Grindr kind of sucks.”

Queer spaces

LGBTQ+ students have dedicated spaces to meet and mingle with other students who themselves identify as queer. These include student organizations, the University’s Gender and Sexuality Resources Center and local queer hangout spots.

Najah Terrell-Walker, junior in Education, founded one such student organization: the Black Queer Collective, also called BlacQ.

Terrell-Walker, a lesbian woman, looked for community in cultural houses and queer-specific places but found it difficult to be herself in those spaces.

“I’d be the only person in there that looks like me,” Terrell-Walker said.

She took on the challenge of creating a space that celebrated the intersection of Black and queer identities. In doing so, she met her girlfriend of one year, who now serves on BlacQ’s executive board alongside Terrell-Walker.

“(In) Spring 2023, I was the president,” Terrell-Walker said. “(Terrell-Walker’s girlfriend) came along with her friend because she was also feeling the same things I thought — she would go to other LGBT groups but would be the only Black woman there.”

Terrell-Walker soon found that her RSO would foster a love connection of her own.

“She just kept attending (BlacQ meetings), and then she became vice president,” Terrell-Walker said.

After summer break, Terrell-Walker’s girlfriend returned to campus, and they began dating.

Alongside their own romances, Terrell-Walker and the BlacQ executive board have helped other Black and queer folks find friendships and romances away from the hustle and bustle of nightlife and dating apps.

“I know a couple of people that have met their partners through my club — like props to me,” Terrell-Walker said unpretentiously.

The dating pool: “I feel like it’s the same 50 people”

Possibly the most stark difference between dating as a straight or queer person is simple: There are significantly fewer queer people than straight people.

Consequently, queer folks have a more limited dating pool. An estimated 22.3% of Generation Z self-identify as LGBTQ+, according to a 2023 Gallup poll.

Yes, 22.3% of Generation Z self-identifying as LGBTQ+ marks a definite increase over other generations, which sit around or below 10%. However, it reflects a serious challenge for queer folks looking for love connections.

“For a person that might be coming to a campus town like Urbana-Champaign from Chicago, or maybe D.C., (they) might find (dating) much more difficult — because the population is much smaller, the dating pool is much smaller,” Ali said. “Honestly, I kind of feel that way now, too, because at the end of the day, I feel like it’s the same 50 people.”

Although statistics indicate that the University has well over 50 LGBTQ+ students, some still feel trapped within their peer group.

“We were just talking in my club how all the (masculine) women in our grade — it’s like three of them,” Terrell-Walker said. “Everybody is like, ‘Where are the studs?’”

Additionally, the tight-knit nature of queer friend groups can add yet another level of frustration to building new romantic relationships.

“I think just everyone knows everyone,” Terrell-Walker said. “Stuff from freshman year came back to sophomore year, and … I thought I was done with that.”

Coping with heterosexism, homophobia

It’s no secret that queer people suffer everything from intolerance to violence because of their identity. It may come as a surprise, though, that C-U — which is by most accounts a progressive, accepting community — is not an infallible LGBTQ+ safe haven.

“The amount of times my boyfriend and I have been called ‘(the f-slur)’ on Green Street is — oh my God — unexpected,” Ali said.

Queer couples often have to make calculated decisions about where and when they express their affection.

Terrell-Walker said she and her girlfriend are aware of the potential consequences of showing PDA on and around campus.

“We are just very aware of our surroundings,” Terrell-Walker said.

Despite instances of homophobia, queer students like Ali and Terrell-Walker have persevered and found themselves in long-term, committed relationships.

“For me, I didn’t give a s—,” Ali said. “I was like, ‘I am going to be queer — loud and proud.’ I don’t really care, and I won’t let incidents like these stifle me.”