Family mourns astronaut’s mom

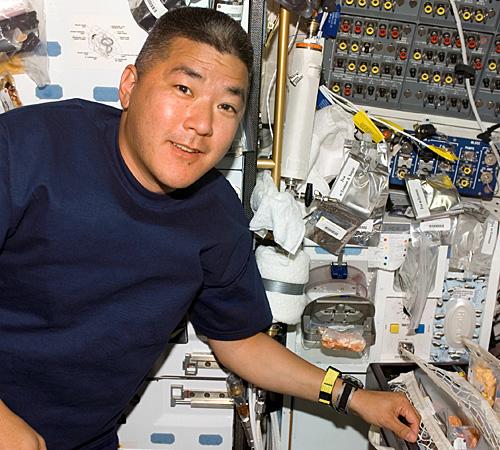

This photo released by NASA shows astronaut Daniel M. Tani as he prepares to use the galley on the middeck of Space Shuttle Discovery on Oct. 24, 2007. Rose Tani, the 90-year-old mother of Daniel Tani who is aboard the international space station died in The Associated Press

December 12, 2007

LOMBARD, Ill. – Rose Tani could have looked back in anger about how she, her husband and their baby son were forced to move from their San Francisco home to an internment camp in Utah during World War II.

And she could have looked for pity when in 1965 her husband died, leaving her with five kids – the youngest just 4 years old.

But she didn’t.

Instead, when she talked about the turns her life had taken, there was nothing except amusing stories about days and people her children would never know.

One of those children, Daniel, is now aboard the international space station, grieving alone as the rest of his family prepares a Sunday memorial service for Rose Tani, who died earlier this week at the age of 90 when her car was struck by a train in this Chicago suburb.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

So, on Friday, two days after the accident, as family members met with news reporters, there were no tears – the family’s attitude influenced by Rose’s own cheerful spirit, even regarding her internment camp stay.

“All I heard was my parents were in the camps and I never even knew until I was a teenager that it was an internment camp,” said Christine Tani, speaking at her mother’s church. “I thought, ‘Those lucky people, they got to go to camp all the time, play with their friends.’ There was no bitterness.”

Which goes a long way in explaining the tone of the half hour Christine Tani and her older brother, Dick Tani, spent talking with reporters. While there was, of course sadness, mostly there were words about a woman who never lost her optimism, even when her very freedom was taken from her.

They told of a woman who worked every day in a school cafeteria until she was 70, only quitting at the request of Christine, her only daughter, who wanted her to baby-sit her youngest child.

They talked about how she’d raise her garage door with her own two hands and back until just a couple years ago when Dan got her an automatic one. They told stories about the nights she volunteered in the church kitchen to feed homeless people, and how even past her 90th birthday, she could be seen on her hands and knees scrubbing the floor.

And when they did touch on the subject of her death, they focused not on the day she drove past a lowered railroad gate and into the path of a train, but on what being behind the wheel said about her.

“She treasured her independence,” said Christine, nodding as her brother talked about the few concessions to age Rose made, including keeping to back roads, driving only to their homes and other familiar sites and letting someone else do the driving at night.

“She was very active,” said Dick, a retired college math teacher who was just months old when he and his parents – both of them born in the United States – were put in an internment camp because of their Japanese ancestry. “She traveled a lot, went to Florida for Dan’s launch,” he said.

“She works hard, she volunteers,” he said, inadvertently lapsing into the present tense that anyone who has lost a loved one knows about.

Dick and Christine Tani spoke of the “special bond” that their brother Dan and their mother had. The youngest of five children by more than a decade and just 4 when his father died, Dan was especially close to his mother, they said.

“He’s holding up,” said Christine, who spoke to her brother for an hour earlier in the day via a video-conferencing system NASA hooked up in her home.

She said being so far away is hard for her brother, and the isolation of being in a place where friends and family can’t just pick up a phone is frustrating for him, but that their e-mails were providing comfort, as were his conversations with family members.

“He’s professional. He said (to NASA) ‘Please give me work,'” she said.

In a brief statement released by NASA, Daniel Tani wrote that he would “proudly complete my mission” before returning to his family. But his words also belied just how difficult that mission is knowing his mother has died.

“She was my hero,” he said.

When Dick and Christine Tani talked about her mom’s recollections of her life, particularly about being yanked from her home with a husband and son during World War II, they kept coming back to their mother’s optimism.

“It was hard, but just in many conversations with her, she always felt she was kind of lucky because they were young and they could start fresh after the war,” said Dick.

Her worries, she told her children, were not for her and her young family, but for the older people who were at the camps, who didn’t have the time she had to start over.

They also talked about their mother’s patriotism.

“She understood that America gave her opportunities that her parents didn’t have and that her children could all succeed” said Christine, an attorney. “One of the things Dan said before his first launch in 2001 was that the same government that sent his parents to internment camps is one generation later sending him to space. That speaks a lot for of course our country and a lot for our family.”

Associated Press Writer Carla K. Johnson in Chicago contributed to this report.