University explores options to relocate African American cultural center

April 30, 2014

The condition of the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center isn’t news to its director, Rory James.

He saw many of the problems when he first interviewed for the position in 2010 and he said the knowledge is commonplace.

Of all seven cultural centers, James said the African American center is in the worst condition.

The cultural center’s current location at 708 S. Mathews St. wasn’t intended to be its permanent location. Before the center moved in during the late 1970s, it housed a fraternity.

Upstairs, the windows are drafty. The stair treads on the three-story building are coming apart, causing a tripping hazard. Beyond the first floor, the building’s structure itself isn’t handicap-accessible, which James said prohibits a population of students from accessing the center’s services.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

In the basement, the tiles contain asbestos and layers of lead paint are peeling from the walls — and these aren’t the only hazards Facilities and Services noted in its March 24 building safety evaluation.

Seven to eight years ago, the center received a new kitchen and a gender neutral bathroom on its first floor, but these fixes don’t address the structural issues of the building.

James said Facilities and Services provides the basic needs for the building, but at this point, it needs more than care.

It needs something extra — institutional priority, which could now be the case.

Following a statement released April 14, the University is exploring different options to relocate the center, Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Renee Romano said.

The statement, addressed to the University on behalf of the African American student body, brings attention to the condition of the cultural center and to claims of decreasing African American enrollment, retention and graduation rates.

The statement requests that the University relocate the cultural center to 1404 S. Lincoln Ave., which Romano said is one of the options on the table.

“It’s not really a slam dunk in the sense that it’s not owned by the University and I don’t know how much repair it needs,” she said. “If they moved from the current facility to that one, I don’t know that they wouldn’t be moving from one bad situation to another.”

She said that she and her team are “moving pretty fast” to see whether any other University-owned structures are available to permanently or temporarily relocate the center while the current building is worked on.

“I’m just trying to keep all options on the table right now,” she said. “I don’t want to go down one road and then find out that we can’t do that, and then we’re stuck.”

However, the University has a plan in its back pocket.

Within an estimated five to eight years, an entirely new cultural center could be built to house all the ethnic studies departments and cultural houses. Romano said this is partly why administration has been reluctant to put a lot of money into maintenance on the African American center.

From her perspective, Romano said the center “seems to deteriorate faster than we can keep up with it.”

“If you think of an older vehicle, you think you want to keep it going, but how much do I keep putting into it that ends up not being a good use of funds?” Romano said.

In addition to office space for the ethnic studies units and cultural houses, the center would house shared multipurpose rooms, classrooms, gathering spaces and even space for displaying art and cultural artifacts.

Romano said a feasibility study for the facility has been completed and a budget and funding plan is now in development. The project is contingent on raising development funds, mostly in the form of fundraising and donations.

“Even if we could raise all the money in the next year, we would have to then begin the real serious planning and that would probably be at least five years out,” she said. “We’re trying to be in a good place for the center with one of these options in the fall.”

Regardless of what is to come in the future, James questions what his staff and his students should do in the present.

“It’s unacceptable. However the future may look, we still have to do something for the now,” he said. “I think that’s the sense of frustration that comes not only from students but staff.”

Bradley Harrison, a senior in AHS and one of the collaborators on the statement, said the letter, which came to fruition as part of the Being Black at Illinois movement, is meant to hold University administration accountable to its own diversity and inclusion statements.

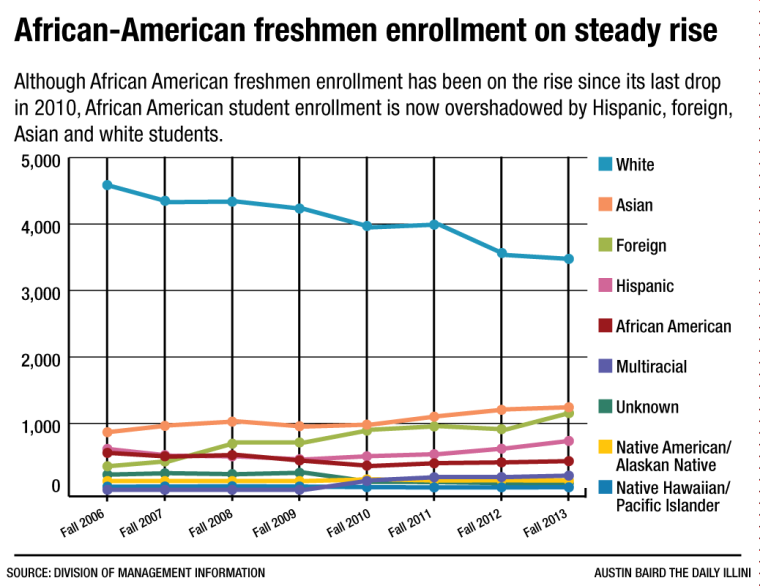

According to first-year enrollment data from the Division of Management Information, African American students comprised 8.84 percent of the 6,802 students in the freshman class of fall 2003, which is the highest percentage of African Americans in a freshman class since 2000.

By fall 2013, African Americans made up 5.91 percent of the new class of 7,331.

“It took us 38 years to get to the highest point, and only about 10 years to get back where we started,” Harrison said. “It’s kind of scary how quick we can go downhill but how long it takes us to go back upward and make progress.”

Similarly, in fall 2000, African American students made up 6.29 percent of enrolled students at the University, but by fall 2013, that had fallen to 5 percent. However, Stacey Kostell, Assistant Provost for Enrollment Management, said that in 2010, the University changed the way it collects ethnicity information, which skews comparisons between years before and after 2010.

Kostell said since 2010, the University has seen an overall increase in student application and admittance, but not all students who are accepted choose to come here. She said this is related very closely with tuition cost, something the University is aware of.

For the 2010-2011 school year, the campus allocated just over $38 million toward financial aid, Kostell said. For the 2014-2015 school year, $66.5 million will be allocated.

“I think there’s certainly interest and the campus is certainly doing their part and trying to make college more affordable,” Kostell said.

She said the money will fund programs such as Illinois Promise, which offers aid to students who are socioeconomically underrepresented, and the President’s Award Program, which assists the University in enrolling high-ability students who are members of historically underrepresented groups and groups that have been difficult to enroll at the University.

Despite these efforts, cost can still be an issue for students. Alex Horton, a junior transfer student in LAS, said he thinks tuition price tag is the number one reason African American enrollment is on the decline.

“We are at a public institution that is really charging private rates,” he said. “I think that’s a problem that needs to be addressed. I feel you ask anybody of any race, gender ethnicity — that is a big problem.”

James also finds it problematic that affordability is preventing the best African American students from enrolling in the University.

“They can go to Mizzou, they can go to Purdue University, they can go to any of our Big Ten peers, they can go to an Ivy and have their tuition paid for,” he said. “Now think about that. They can go to a private school for cheaper than coming to a public school. I find that very problematic.”

Regardless of how bad someone wants to be an Illini, potential students are going to make the most economically feasible decision, James said.

A sense of community plays a big role in student retention as well, said Horton, president of Salango, Pennsylvania Avenue Residence Hall’s Black Student Union. He feels that black student unions go a long way to create this sense in a dorm.

“I love Salango because it’s a community,” he said. “It’s where you can just stop every Tuesday from nine to 10, whatever you’re doing, come and just relax.”

Harrison said everything ties back into the cultural center, which plays a major role in recruiting and retaining African American students.

“If you see something beautiful that has African American on it at another institution and then you come here and see something in horrible conditions, I would be more inclined to go to the university that has the beautiful facilities and resources designated for me, as an African American student,” he said.

Harrison noted that he sees the cultural center’s current condition as symbolic of how the University sees its African American student population.

“The symbolism of the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center totally correlates with the racial climate of this campus,” he said. “Things aren’t good for us as African Americans, or probably as any minority on this campus, just based off of the experiences that we have.”

Harrison added that the cultural houses on campus are meant to be safe zones for minorities on campus — “however, when we go there, they’re horrible.”

In the meantime, whether the cultural center moves into a new facility or not, James said something needs to be done. Over the past months, his staff has been working to clean out clutter that has collected over the years, and he said things are moving along.

However, James questions whether it is the responsibility of students and staff to address the building’s larger structural issues.

“I’m not a carpenter,” he said. “If there’s a hole in the floor, I don’t think the director should be the (person) who’s working on it.”

Tyler can be reached at [email protected] and @TylerAllynDavis.