University develops MRI develops with fastest speed in the world

May 11, 2015

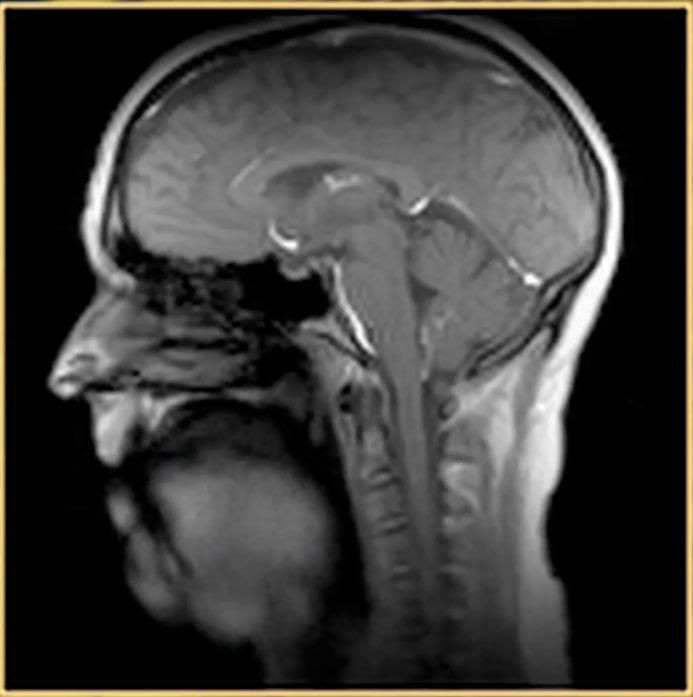

University researchers developed a new Magnetic Resonance Imaging designed to have a faster speed than current MRIs, allowing it to visualize motions of muscles clearly without interfering with normal speaking processes.

The new MRI has good spatial and temporal resolution with a speed of 100 frames per second, said Maojing Fu, graduate student at the University.

Brad Sutton, associate professor in bioengineering and University alumnus, said he and his colleagues are looking into how the new MRI can function in helping aging people by examining the movements of muscles in their mouth critical for speech and swallowing.

He said the machine will also help people, especially infants, who have a collapsed palate and require surgery to correct the split muscles.

“By going faster, we are able to catch a couple of images on its way and you can see how the muscle is contracting and how (it) is interacting with the other muscle and how’s that affecting its trajectory,” Sutton said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Aaron Johnson, assistant professor in the department of speech and hearing science, received funding from the Campus Research Board Programs and a K23 Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health to study the voices of older adults and how they can use vocal training to improve voices.

Fu said people have been studying speech for a long time, but only by listening to audio recordings, instead of through visual evidence.

Using the new technique, researchers can not only hear the sound but also watch it at arbitrary angles and resolutions.

“I think that’s the biggest change,” Fu said, “That provides an entire new side of tool for people to understand and analyze the speech, not just hearing. So that’s just one side that will fundamentally change the field.”

Typical MRIs only capture 10 frames per second, which are unable to capture the movement of muscles critical in producing sound during speech or singing, but the new MRI makes it feasible, Johnson said.

He said his goal is to be able to see how the muscles and structures in the mouth change to create a better voice.

Sutton added they are still advancing the new MRI to capture 166 frames per second and three-dimensional visualization.

“And what that will allow us to do is we can look at any plane we want to,” Sutton said.

He said the MRI will also allow surgeons to look at how well they are performing corrective surgeries for children with collapsed palates because the operation requires them to reattach split muscles.

The surgeries for children are largely based on anatomy because there is not a lot of dynamic imaging available, Sutton said.

“I think that’s (what) our biggest impact will be, taking people from structure to function in these types of acquisitions,” Sutton said.

The development of the new MRI technique is a collaborative work, Fu said. The framework was developed with Zhi-pei Liang, professor in electrical and computer engineering.

Sutton extended and finalized the technique into the speech MRI context. With Johnson, who has a 10-year working experience as a professional singer in Chicago choirs and clinical applications, they can use the new MRI to answer questions across multiple fields.

Fu said the new MRI is not a market-oriented product because the fundamental driving force in doing research is to figure out the unknown and the boundaries and limits of what people cannot do.

In the future, Sutton said the MRI can be used to diagnose functional deficiencies researchers currently cannot identify in patients. It will also allow researchers to produce a wide range of dynamic imaging in the scientific field to look at other types of functions in the body.

Sutton said the major challenge going forward will be extracting the information needed for speech and science applications from thousands of images coming out just for a short scan due to the absolutely fast speed.

Johnson said the Beckman Institute provided the essential infrastructure, the physical space and resources to support their disciplinary work.

“We’ve been very lucky to be able to get funding and money to do the research,” Johnson said. “Running an MRI machine is a very expensive endeavor so the fact that we have two machines right here is really incredible.”