Lack of planning could leave some families in crisis

Source: State of the States

Feb 22, 2018

When Nora Handler’s mother died 20 years ago, the family was left without a plan.

Handler is one of eight siblings. Four of her siblings have intellectual or developmental disabilities, and when her mother passed, there was no plan for her siblings’ care.

“It literally changed our lives,” she said.

A new study suggests less than half of parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities make plans for how their child will be cared for if a parent dies or is unable to continue caring for the child.

Meghan Burke, associate professor of special education, created a web-based national survey that asked over 380 parents of people with disabilities about how they plan for their children’s care. The survey used an 11-item scale, looking at how well parents were completing each item.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

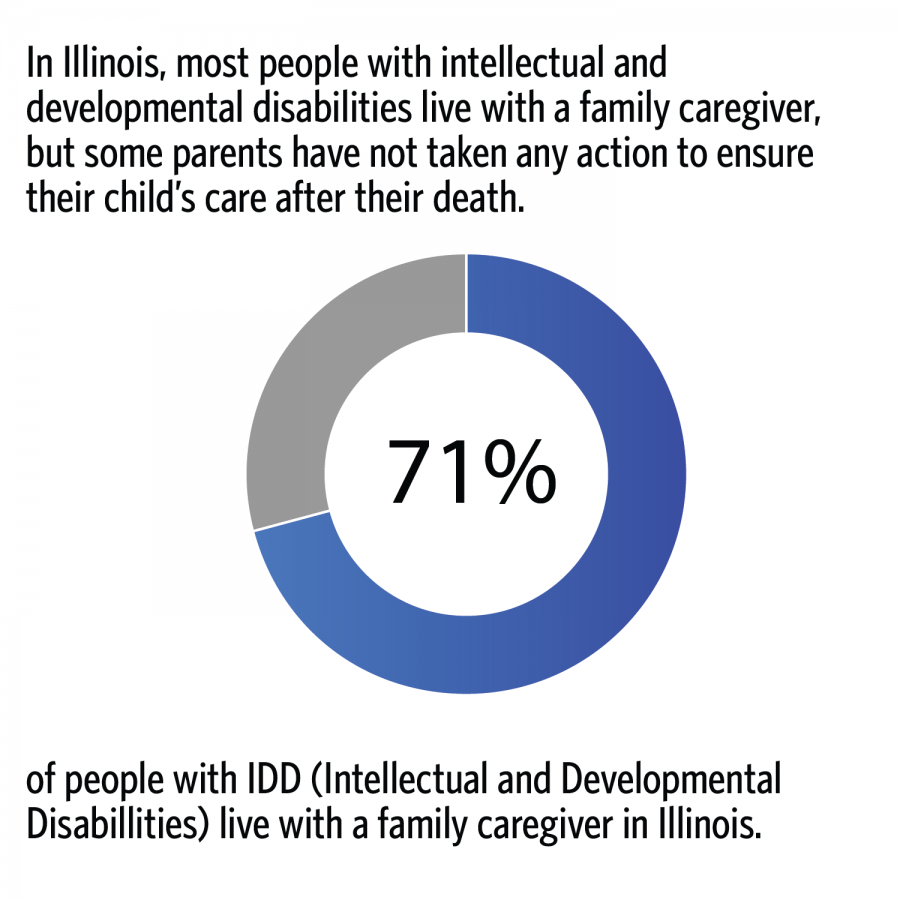

In Illinois, 71 percent of people with disabilities live with a family caregiver, according to the State of the States in Developmental Disabilities Project. Meanwhile, Burke said, 12 percent of parents reported they had taken no action to ensure their child’s needs were met in the future.

Developmental disabilities are those that have their onset before age 18 and lead to altered courses of development, said Marie Channell, an assistant professor in developmental psychology and the principal investigator in the University’s Intellectual Disabilities Communication Lab.

Intellectual disabilities, a narrower category under developmental disabilities, she said, are characterized by a cognitive impairment, usually defined by a low IQ score. Difficulty with daily life or practical skills is also common.

Disabilities under this category can include Down syndrome, some forms of autism and cerebral palsy.

Future planning is a fairly new issue, Burke said. Traditionally, people with developmental disabilities have had shortened life spans, but are now living increasingly longer and are outliving their parents.

Burke’s survey found that families with more resources, knowledge and training were more likely to engage in future planning, suggesting interventions might be needed to increase training for the future, Burke said.

Before Handler began educating families about future planning through her work in Supporting Illinois Brothers and Sisters, an organization providing support to siblings of people with disabilities, her family faced an incredible challenge: learning how to care for her siblings while still coping with their mother’s death.

“I had a kid, a husband, a life, and so did my older sister. It turned everything upside down,” she said.

Handler’s mother had been her brothers’ primary caretaker, she said, but she did not plan effectively enough for a future without her. She had not put them on waiting lists for residential or other services, or financially planned in a way that allowed the brothers to receive government benefits, which, she said, are essential to affording care for someone with a disability.

Burke said good concrete actions for future plans include creating a special needs trust, signing a letter of intent and securing residential placement. Additionally, she said siblings need to learn how to care for their sibling with a disability, so they can assume that caregiving role.

“You all of a sudden have this learning curve where you’re trying to figure out everything a parent figured out over 40 years,” Handler said.

Parents of children with a disability start learning how to care for them the day the child is diagnosed. If siblings aren’t included in learning about their brother or sister’s needs, or where to find services for them, they are not being educated at all, Handler said.

Needs of people with intellectual disabilities can range pretty drastically, said Channell, ranging anywhere from additional skills training to requiring significant supports for daily life.

One of the barriers for people wanting to future plan is the lack of capacity of service systems. Burke said Illinois has some of the lowest system funding in the country.

“One of the things I’ve learned over the 20 years of doing this is that people with disabilities are part of the richness of our culture, of our world, and they’re not valued. They are the people that, whenever we want to save money, we cut,” Handler said.